4. Reaganomics

Reagan Era

The election of Reagan inaugurated the ascendency of the Old Right, who used a social conservative platform as a Trojan Horse to insinuate a neoliberal agenda, to be implemented as Reaganomics. Due to Reagan, Republicans took control of the Senate for the first time since 1954, and conservative principles dominated his economic and foreign policies. Reagan solidified conservative Republican strength with tax cuts, a greatly increased military budget, continued deregulation, a policy of rollback of Communism rather than containment, and appeals to conservative morality. As a result, the 1980s and beyond became known as the “Reagan Era.”

As a result, “what Americans now call conservatism,” as Leo P. Ribuffo noted, “much of the world calls liberalism or neoliberalism.”[1] Speaking of the influence of the well-financed neoliberal agenda, Jane Mayer noted, “By the early 1980s, the reversal in public opinion was so significant that Americans’ distrust of government for the first time surpassed their distrust of business.”[2] As Reagan had touted in his inaugural address on January 20, 1981, “Government is not the solution to our problem. Government is the problem.”[3]

Reagan was launched into national prominence with “A Time for Choosing,” a speech he presented on behalf of Barry Goldwater presidential campaign in 1964. The speech was a diatribe against the excesses of government spending and the futility of social programs such as welfare and social security: “The Founding Fathers knew a government can’t control the economy without controlling people. And they knew when a government sets out to do that, it must use force and coercion to achieve its purpose. So, we have come to a time for choosing.” According to Reagan:

Whether we believe in our capacity for self-government, or whether we abandon the American Revolution and confess that a little intellectual elite, in a far distant capital can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves. You and I are told we must choose between a left or right, but I suggest there is no such thing as a left or right. There is only an up or down. Up to man's age-old dream – the maximum of individual freedom consistent with law and order – or down to the ant heap of totalitarianism.[4]

The speech raised $1 million for Goldwater’s campaign, and is considered the event that launched Reagan’s political career.[5] Soon afterwards, Reagan was asked to run for Governor of California; he ran for office and won election in 1966. Reagan was later dubbed the “Great Communicator” in recognition of his effective oratory skills.

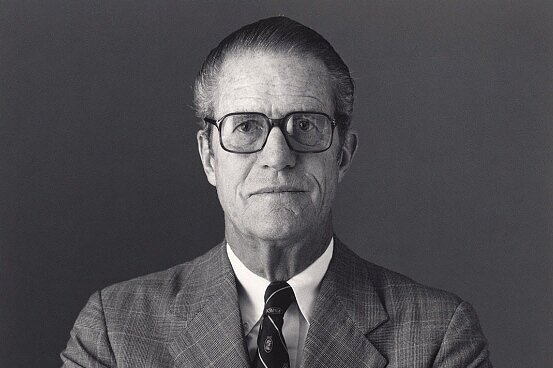

Reagan on William F. Buckley’s Firing Line.

Famed historian of American conservatism George H. Nash said William F. Buckley Jr. was “arguably the most important public intellectual in the United States in the past half century… For an entire generation, he was the preeminent voice of American conservatism and its first great ecumenical figure.”[6] Buckley’s primary contribution to politics, which was a fusion of traditional American political conservatism with laissez-faire economic theory and anti-communism, laid the groundwork for the new American conservatism of Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan in 1981. Known as the First New Right (1955–64), it adopted the domestic Anti-New Deal conservatism of the Old Right, but broke with their non-interventionism, advancing a foreign policy of staunch anti-communism.

Buckley threw the support of his reputation behind Reagan, including several Firing Line specials structured to showcase Reagan’s great potential as a national and international leader. Speaking of Buckley’s influence, National Review editor Neal Freeman said, “That was the meaning of Firing Line. That was the meaning of National Review and its political triumph with Reagan. Other people could have made it respectable. Nobody else could have made it stylish.”[7] According to Buckley’s publisher Henry Regnery, Buckley “has given the conservative movement a style and rhetoric of its own, and has done more than anyone else to reconcile potentially conflicting viewpoints into a coherent intellectual force.”[8]

Heather Hendershot, professor of film and media at MIT, who has studied the history of Firing Line remarked that the program’s long run shows “a country turning from left to right, from the Great Society to the Reagan Revolution and beyond.” The life of the program reveals “an America that weathered massive civil unrest in the 1960s, the collapse of the presidency in the 1970s, and the rise of conservative approaches to foreign policy in the 1980s: an America that, by the 1990s… had emerged as a society in which certain key cultural values had shifted left, even as the Republican Party had continued its rightward shift, pulling the Democratic Party along in its wake.”[9]

Manhattan Institute

Charles Murray of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), whose book The Bell Curve drew heavily on research funded by the neo-Nazi and eugenicist Pioneer Fund.

As indicated by Eduardo Porter, writing for the New York Times, “Few ideas are so deeply ingrained in the American popular imagination as the belief that government aid for poor people will just encourage bad behavior,” a notion that has been shared not only persisted among Republicans, but it was President Bill Clinton, a Democrat, who put an end to “welfare as we know it.”[10] The proposition was buttressed by scientific racism of Charles Murray of the neoconservative American Enterprise Institute (AEI), whose book The Bell Curve drew heavily on research funded by the neo-Nazi and eugenicist Pioneer Fund. The book was part of a consolidated strategy on the part of the American Right, funded by a legion of think tanks and foundations, to fundamentally reeducate the American people against the desirability of social welfare programs, convincing them that giving free reign to big business, in the end, was in the best interest of everyone.

The War on the Poor was facilitated when many of the world’s economies were suffering as a result of the Oil Crisis and stagflation by the 1970s, permitting Reagan and Thatcher to propose their drastic reforms, breaking down trade barriers and reducing government power, to supposedly revitalize their stagnant economies, thus ushering in the modern rush of neoliberal policy implementations. For nearly four decades, conservative foundations like the Bradley, Olin and Scaife, and think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and Manhattan Institute, mounted a concerted campaign to reshape politics and public policy according to neoliberal principles of selfishness and bigotry. These organizations pursue an agenda based on industrial and environmental deregulation, the privatization of government services, deep reductions in federal anti-poverty spending and the transfer of authority and responsibility for social welfare from the national government to the charitable sector and state and local government.

Lewis F. Powell Jr.

Starting in the 1970s and 1980s several conservative charitable foundations joined the Carthage Foundation, also founded by Richard Mellon Scaife in 1964, to fund a pro-business vision of Lewis F. Powell Jr., the future Supreme Court justice who was then an eminent corporate lawyer from Richmond, Virginia. Marxist academic David Harvey traces the rise of neoliberalism in the US to what has been referred to as the Powell Memo.[11] The confidential memorandum written by Powell in 1971 for the US Chamber of Commerce proposed a road map to defend and advance the free enterprise system against perceived socialist, communist, and fascist cultural trends. A similar sentiment had been expressed by M. Stanton Evans, who had studied with Ludwig von Mises, who captured conservatives’ concerns in his 1965 book, The Liberal Establishment: Who Runs America…and How. He declared that “the chief point about the Liberal Establishment is that it is in control.” In response, Evans agitated for a “counter-establishment.”[12]

According to Jane Mayer, author of Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, “…it was Powell’s memo that electrified the Right, prompting a new breed of wealthy ultraconservatives to weaponize their philanthropic giving in order to fight a multifront war of influence over American political thought.”[13] Powell called on corporate America to fight liberal dominance, urging them to wage “guerilla warfare” against those seeking to “insidiously” undermine them. He urged conservatives to follow a program that included funding scholars who supported free enterprise, and publishing books and papers from popular magazines and scholarly journals.

Antony Fisher

The leading right-wing foundations are connected through the Atlas Network, founded by Antony Fisher, who would go on to found another 150 or so free-market think tanks around the world. BBC documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis recounts how around 1950, after reading the Reader’s Digest version of Hayek’s Road to Serfdom, British libertarian Antony Fisher, an Eton and Cambridge graduate who believed socialism and Communism were overtaking the democratic West, sought Friedrich Hayek’s advice about what should be done. Hayek advised Fisher to start “a scholarly institute” that would wage a “battle of ideas.” If Fisher succeeded, Hayek told him, he would change the course of history. After visiting Foundation for Economic Education in 1952, Hayek encouraged Antony Fisher to found the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), which experienced the height of its influence during the right-wing Tory administration of Margaret Thatcher.[14] Fisher’s partner in the venture, Oliver Smedley, wrote to Fisher saying that they needed to be “cagey”:

Imperative that we should give no indication in our literature that we are working to educate the Public along certain lines which might be interpreted as having a political bias. In other words, if we said openly that we were re-teaching the economics of the free-market, it might enable our enemies to question the charitableness of our motives. That is why the first draft (of the Institute's aims) is written in rather cagey terms.[15]

Prime minister Margaret Thatcher meets free market economist Friedrich von Hayek at IEA.

Since 1974, the IEA played a role in developing a world-wide network of similar institutions across the globe.[16] Among these were several think tanks like the Fraser Institute of Canada in 1974. Fisher went to New York where in 1977 he set up the International Center for Economic Policy Studies (ICEPS), later renamed the Manhattan Institute. The incorporation documents were signed by prominent attorney Bill Casey, later Director of the CIA. The Atlas Economic Research Foundation (named after Ayn Rand’s book, Atlas Shrugged) was created in 1981, but simply known as the Atlas Network.

Heritage Foundation

President Reagan and Heritage founder Ed Feulner (right) at the Heritage Foundation's 10th anniversary gala in 1983.

Of seventy-six economic advisers on Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign staff, twenty-two were from Mont Pelerin, providing them the opportunity to push their neoliberal agenda. Following Margaret Thatcher’s victory, Mont Pelerin launched an ambitious overhaul of the right-wing Heritage Foundation, importing several British economists from Mont Pelerin in anticipation of the 1980 Presidential run by Ronald Reagan.

The Heritage Foundation became a favorite beneficiary Richard Mellon Scaife, who contributed more than $23 million from 1975 to 1998.[17] According to Scaife, “In those days you had the American Civil Liberties Union, the government-supported legal corporations [neighborhood legal services programs], a strong Democratic Party with strong labor support, the Brookings Institution, the New York Times and Washington Post and all these other people on the left—and nobody on the right.”[18] Scaife had written a previously private, still-unpublished memoir, A Richly Conservative Life, that describes how he and a handful of other influential conservatives began meeting during the Cold War, at first informally, to plot against the country’s liberal influence.

Joseph Coors

In 1970, Nixon’s speechwriter Patrick Buchanan sent a memo to the president, pleading for “a conservative counterpart to Brookings.” Three years later, Paul Weyrich responded to the call when he and his friend Ed Feulner, with funding from Joseph Coors, of the Coors beer empire and a supporter of the John Birch Society.[19] Feulner, who became President of the Heritage Foundation, was a member of the Mont Pelerin Society, a trustee of William F. Buckley and Frank Chodorov’s Intercollegiate Society of Individualists from 1973, and eventually president of the Philadelphia Society from 1982–83.

Paul Michael Weyrich (1942 – 2008)

According to David Grann, in “Robespierre Of The Right,” his article about Weyrich for the New Republic, “if anything embodied that power structure, it was the Brookings Institution, a liberal think-tank that for decades had stoked the New Deal with ideas.”[20] Weyrich’s “right-hand man” was Laszlo Pasztor, an activist in various Hungarian rightist and Nazi-linked groups.[21] Weyrich was active in the Young Republicans from 1961 to 1963 and in Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign.

Although Weyrich was mainly influential in mobilizing Evangelical Protestants to get involved with politics, Weyrich himself was a conservative Catholic and a member of Opus Dei.[22] Weyrich, who had converted from Roman Catholicism to the Eastern Orthodox Church after Vatican II, positioned himself as a defender of traditionalist sociopolitical values of states’ rights, dominionism, marriage, and anti-communism, and as a staunch opponent of the New Left. He advocated a revival of McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee with the aim of identifying and removing communists from the media, which he contended was still infiltrated by the former Soviet Union.

Franz Joseph Strauss

Weyrich worked closely with Franz Joseph Strauss, Bavarian head of state, a longstanding fixture of Le Cercle and a very close friend and associate of Third Reich banker Hermann Abs. Strauss was Chairman of the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), which is represented in a common faction with Adenauer’s CDU, called CDU/CSU. In 1953, Strauss became Federal Minister for Special Affairs in Adenauer’s second cabinet. According to T.H. Tetens, the British press once referred to Strauss as “the most dangerous man in Europe.” [23] As head of the state government of Bavaria, Strauss saw to it that funding was provided to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), which formed the Anti-Bolshevik Block of Nations (ABN). When Strauss came to the United States in the early 1970’s, Weyrich and Strauss’ Washington representative, Armin K. Haas, planned his schedule, including Capitol Hill appointments. Joseph Coors also helped Haas make new political contacts in Congress.[24]

Weyrich’s Heritage Foundation took a leading role in the conservative movement during the presidency of Ronald Reagan, whose policies were taken from Heritage’s policy study Mandate for Leadership. The New York Times called it “the manifesto of the Reagan revolution.”[25] The overall direction of the study was undertaken by Charles Heatherly, a former field director of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI). Specific suggestions related to spending included raising the defense budget and reducing personal income tax rates. At the first meeting of his cabinet, President Reagan passed out copies of Mandate for Leadership, and many of the study’s authors were recruited into the White House administration. According to its authors, around 60% of Mandate for Leadership’s 2,000 proposals had been implemented or initiated at the end of Reagan’s first year in office.[26] The Washington Post called it “an action plan for turning the government toward the right as fast as possible.”[27]

Mankind Quarterly

Lord Malcolm Douglas, the brother of the host of Rudolph Hess on his secret flight to England in 1940, and his wife Lady Douglas, who helped establish a branch of the Military and Hospitaller, the Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem in the U.S.

When Coors established the Heritage Foundation, he chose Roger Pearson as co-editor of the foundation’s publication Policy Review. In 1961, Pearson founded Mankind Quarterly along with Robert Gayre, Henry Garrett, Corrado Gini, Luigi Gedda, Otmar von Verschuer and Reginald Ruggles Gates.[28] Mankind Quarterly was published by the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics (IAAEE), founded in Scotland in 1959, whose principle benefactor was Wickliffe Draper. The American branch of the IAAEE was founded by Lord Malcolm Douglas, the brother of the host of Rudolph Hess on his secret flight to England in 1940. Hess sought to meet with the British aristocratic circles known as the Cliveden Set, who were sympathetic to Hitler. When Douglas and his wife Lady Douglas came to the US, he helped establish a branch of the Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem, a racist network based in Scotland.[29] Nelson Bunker Hunt, his brother William Herbert Hunt and Senator Jesse Helms, who also belonged to the Order of Saint Lazarus, were also members of the IAAEE.[30]

Several founders of the IAAEE were intimately associated with H. Keith Thompson of the National Renaissance Party (NRP). IAAEE co-founder, eugenicist and segregationist Dr. Charles Callan Tansill of Georgetown University, met frequently at George Sylvester Viereck’s apartment, along with Boris Brasol’s associate Lawrence Dennis, Alfred Kinsey, and Harry Elmer Barnes, and other historians.[31] IAAEE founder Charles Lee Smith worked closely with the NRP. Smith edited the Truth Seeker, the Northern League’s publication. Eustace Mullins and Matt Koehl were regular contributors. Smith also attended the Northern League’s meeting at Teutoburg Forest in honor of Arminius. In 1959, Smith was in England, where he addressed a meeting headed by Colin Jordan.[32]

From the beginning, GRECE and its journal Nouvelle Ecole were allied to the Northern League, Mankind Quaterly and the AAEE. Nouvelle Ecole’s comité de patronage included Roger Pearson, Robert Gayre, Henry Garrett and former Truth Seeker writer Robert Kuttner. Nouvelle Ecole’s American representative was H. Keith Thompson’s friend Donald Swann.[33]

Anthropologist Donald Swann, who was the IAAEE’s treasurer, was suspended from Queens College for “neo-Nazi,” “anti-Semitic” activities, and his association with Thompson.[34] Swann praised Thompson as “a fearless American patriot [who] has spoken out against the smears of the Jewish ‘gestapo’.”[35] In 1966, Swann was arrested and indicted on twelve counts of mail fraud. U.S. marshals at the time of his arrest discovered an arsenal of weapons, photographs of Swann with members of the American Nazi Party, a “cache of Nazi paraphernalia, including swastika flags… and hundreds of anti-Semitic, anti-Negro and anti-Catholic tracts.”[36] Nevertheless, upon his release Swann remained one of the most important members of the inner circle close to Harry Frederick Weyher, Jr. and Wickliffe Draper, reemerging as a contributor to IAAEE publications and later receiving a number of Pioneer grants.[37] Another initial IAAEE member, Herbert C. Sanborn, chair of the Department of Philosophy and Psychology at Vanderbilt University until 1942, had also been a long-time Nazi sympathizer, who blamed the International Jewish banking conspiracy for World War II and then participated in the postwar campaign, orchestrated by Thompson, for the release of Hitler’s chosen successor, former chief of the German navy Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz.[38]

Robert Gayre

Mankind Quarterly’s avowed purpose was to counter the “Communist” and “egalitarian” influences that were allegedly causing anthropology to neglect the reality of racial differences.[39] “The crimes of the Nazis,” wrote Gayre, “did not, however, justify the enthronement of a doctrine of a-racialism as fact, nor of egalitarianism as ethnically and ethically demonstrable.”[40] Nazi eugenicist Von Verschuer was on the editorial advisory board of the journal before his death in 1970.[41]

National Renaissance Party member Eustace Mullins, author of the conspiracy classic Secrets of the Federal Reserve, collaborated on racial ideas about “biopolitics” with Kuttner.[42] In 1966, when the American Mercury which had previously been edited by General Edwin A. Walker of the John Birch Society, announced a change of editorship, among the new editors was Kuttner. The first issue, for which Kuttner was an editor, featured a piece by Revilo P. Oliver, who was expelled from the John Birch Society for his open anti-Semitism. The issue also included a tribute to Klansman Col. Earnest Sevier Cox, who is described as “the English-speaking world’s foremost racial historian.” Kuttner was also a contributor to Willis Carto’s Spotlight. A contribution of his to Spotlight was reprinted in the Northern League’s The Northlander in 1977.[43]

Henry E. Garrett was an American psychologist and segregationist, and President of the American Psychological Association in 1946 and Chair of Psychology at Columbia University from 1941 to 1955. Garrett, whose efforts were financially supported by Draper, was a strong opponent of the 1954 United States Supreme Court’s desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which he predicted would lead to “total demoralization and then disorganization in that order.”[44] After he left Columbia, Garrett became involved in the IAAEE and the Northern League. He served as a Director of the Pioneer Fund from 1972 to 1973, and was involved in the White Citizens’ Councils and the Liberty Lobby, and provided expert testimony for the defense in Brown v. Board of Education. Corrado Gini was leader of fascist Italy’s eugenics movement and author of a defence of Mussolini in 1927 called The Scientific Basis of Fascism.[45] Gates, who was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1931, was a strong opponent of interracial marriage and “argued that races were separate species.”[46]

Pearson was also elected to head University Professors for Academic Order (UPAO), composed of members of the Heritage Foundation, the Reagan Administration and the Mont Pelerin Society, including Milton Friedman and Friedrich von Hayek.[47] Between 1973 and 1999, the Pioneer Fund spent $1.2 million on Pearson’s activities, most of which was used for the Institute for the Study of Man, which Pearson directed and which acquired the Mankind Quarterly in 1979.[48] Pearson also served on editorial board of the several institutions, including the Foreign Policy Research Institute, and the American Security Council, and a number of conservative politicians wrote articles for Pearson’s Journal on American Affairs, including Jesse Helms and Jack Kemp.

War on the Poor

William Greider’s bestseller Who Will Tell the People: The Betrayal of American Democracy revealed: “Not withstanding its role as ‘populist’ spokesman, Weyrich’s organization, for instance, has received grants from Amoco, General Motors, Chase Manhattan Bank [David Rockefeller] and right-wing foundations like Olin and Bradley.”[49] The John M. Olin Foundation was established in 1953 by John M. Olin, president of the Olin Industries chemical and munitions manufacturing businesses. Between 1958 and 1966, the Olin Foundation secretly laundered $1.95 million through the foundation. Many of these funds went to anti-Communist intellectuals and publications.[50] The television show Firing Line, hosted by William F. Buckley, an honoree of the Manhattan Institute, was financially supported by the Olin Foundation.

In 1977, Olin had raised the prestige of his foundation by hiring William Simon, a colleague of Irving Kristol, as its president. Simon, a leverage buyout pioneer, was United States Secretary of the Treasury under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Simon served as President of the Olin Foundation and as trustee of the John Templeton Foundation. He also served on the boards of many of America’s premier think tanks, including the Heritage Foundation and the Hoover Institution. The man who distinguished the Olin Foundation even more than Simon was its executive director, Michael Joyce, a former liberal who had also become a neoconservative acolyte of Kristol’s. The National Review described Joyce as “the chief operating officer of the conservative movement.”[51]

Lynde Bradley and his brother Harry Lynde Bradley founded the Allen-Bradley Company in Milwaukee which serviced the defense contract industry. Along with Fred Koch, father of the infamous Koch brothers, Harry was a founding member of the John Birch Society, frequently hosting its founder Robert Welch as a speaker at company sales meetings.[52] Three books in particular, written by Bradley-funded writers played key roles in this effort: Wealth and Poverty by George Gilder (1981); Losing Ground (1984), by Charles Murray and Beyond Entitlement by Lawrence M. Mead. Gilder attended Phillips Exeter Academy, and David Rockefeller, a college roommate of his father, was deeply involved with his upbringing.[53] As well as being a member of Buckley’s Philadelphia Society, Gilder also became the program director of the Manhattan Institute.

Gilder’s Wealth and Poverty advanced a practical and moral case for supply-side economics and capitalism during the early months of the Reagan administration and made him Ronald Reagan’s most quoted living author. The theory of supply-side economics was started by economist Robert Mundell during the Ronald Reagan administration. It is a macroeconomic theory that argues economic growth can be most effectively created by investing in capital and by lowering barriers on the production of goods and services. It. According to supply-side economics, consumers will then benefit from a greater supply of goods and services at lower prices; furthermore, the investment and expansion of businesses will increase the demand for employees and therefore create jobs. Typical policy recommendations of supply-side economists are lower marginal tax rates and less government regulation.[54]

Charles Murray has had a Bradley Foundation research fellowship at AEI. Charles Murray served in the Peace Corps ended until 1968, and then worked in Thailand on an American Institutes for Research (AIR) covert counter-insurgency program for the US military in cooperation with the CIA.[55] While at the Manhattan Institute, Murray wrote Losing Ground, in which he argued that poverty is the result not of economic conditions or injustices, but to individual failings, maintaining that most government-sponsored anti-poverty programs were ill-conceived and should be eliminated. Murray teamed up with the late Harvard psychologist Richard Hernstein to write the book the Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (1984), which argued that poverty is the result not of social conditions or policies, but of the inferior genetic traits of a sub-class of human beings. It relied heavily on research financed by the Pioneer Fund.[56]

As many as seventeen researchers cited in the bibliography of The Bell Curve have contributed to Mankind Quarterly. The authors recommend two books on race and intelligence by Audrey Shuey and Frank C. J. McGurk, who were leading members of the IAAEE, in support for the argument that IQ tests are not racially biased. The work of Richard Lynn, a psychologist and former board member and grantee of the Pioneer Fund, assistant editor of Mankind Quarterly, was among the main sources cited in the book The Bell Curve and he was one of 52 scientists who signed an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal entitled “Mainstream Science on Intelligence,” which endorsed a number of the views presented in the book.

[1] Leo P. Ribuffo. “20 Suggestions for Studying the Right now that Studying the Right is Trendy,” Historically Speaking Jan 2011 v.12#1 pp 2–6, quote on p. 6.

[2] Mayer. Dark Money.

[3] Ronald Reagan. “Inaugural Address, January 20, 1981.” (The American President Project).

[4] “A Time for Choosing.” PBS.

[5] Peter Schweizer & Wynton C. Hall. Landmark Speeches of the American Conservative Movement (Texas A&M University Press, 2007). p. 42.

[6] George H. Nash. “Simply Superlative: Words for Buckley.” National Review (February 28, 2008).

[7] John R. Coyne Jr. “The Buckley Legacy in Voice and Print.” The American Conservative (February 15, 2017).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Eduardo Porter. “The Myth of Welfare’s Corrupting Influence on the Poor.” Washington Post (October 20, 2015).

[11] David Harvey. A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 43.

[12] Jane Mayer. Dark Money.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Philip Mirowski & Dieter Plehwe. The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 387.

[15] Adam Curtis. “The Curse of Tina.” BBC (September 13, 2011).

[16] “Institute for Economic Affairs,” Think Tank Watch. Retrieved from http://thinktank-watch.blogspot.ca/2007/12/institute-of-economic-affairs.html

[17] Robert G. Kaiser & Ira Chinoy. “Scaife: Funding Father of the Right.” Washington Post (May 2, 1999).

[18] Ibid.

[19] Teacher. Rogue Agents, p. 388 f. 385.

[20] David Grann. “Robespierre Of The Right.” New Republic (October 26, 1997); “Scaife Foundations.” Conservative Transparency (accessed March 8, 2018).

[21] Lee. The Beast Reawakens. p. 303.

[22] Ed Brayton. “Paul Weyrich Expose.” Dispatches From the Culture Wars (10 August 2004).

[23] Bellant. The Coors Connection, p. 2.

[24] Ibid., p. 2.

[25] Dowie Mark. “Learning From the Right Wing.” New York Times (July 6, 2002).

[26] Lee Edwards. The Power of Ideas (Ottawa, Illinois: Jameson Books, 1997). pp. 41–68.

[27] Joanne Omang. “The Heritage Report: Getting the Government Right with Reagan.” Washington Post (November 16, 1980).

[28] Bellant. Old Nazis, the New Right and the Republican Party, p. 46.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Thompson interview with Stimley. Kerry Bolton. “H. Keith Thompson Jr.”

[32] Coogan. Dreamer of the Day, p. 478.

[33] Ibid., p. 533.

[34] Kerry Bolton. “H. Keith Thompson Jr.”

[35] William H. Tucker. The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund (University of Illinois Press, 2007), chap 3.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Charles Lane. “The Tainted Sources of ‘The Bell Curve’.” New York Review of Books (December 1, 1994).

[40] Robert Gayre. “The Mankind Quarterly Under Attack,” The Mankind Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 2 (October–December 1961), p. 79.

[41] British Eugenics Society website, cited in “The Heritage Foundation: Power Elites: The Merger of Right and Left” Retrieved from http://watch.pair.com/heritage.html

[42] John P. Jackson. Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case against Brown v. Board of Education (New York University Press, 2005). pp. 60-65.

[43] Michael Billig. “Psychology, Racism, and Fascism.” (Searchlight, 1979). Retrieved from http://www.psychology.uoguelph.ca/faculty/winston/papers/billig/billig.html

[44] Tucker. “A Closer Look at the Pioneer Fund”; Mark Whitman. “Part Two: The Trial Level, III. Rebuttal in Virginia, 3. Henry Garrett.” Brown V. Board of Education: A Documentary History (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, Inc., 2004 [1993]), pp. 80–83.

[45] Charles Lane. “The Tainted Sources of ‘The Bell Curve’.”

[46] Andrew S. Winston. “Science in the service of the far right: Henry E. Garrett, the IAAEE, and the Liberty Lobby - International Association for the Advancement of Ethnology - Experts in the Service of Social Reform: SPSSI, Psychology, and Society, 1936-1996.” Journal of Social Issues (Spring 1998), 54: 179–210.

[47] Bellant. Old Nazis, the New Right and the Republican Party, pp. 63-4.

[48] Tucker. The Funding of Scientific Racism, p. 170.

[49] William Greider. Who Will Tell the People: The Betrayal of American Democracy (Touchstone Books, 1993), p. 28.

[50] Mayer. Dark Money.

[51] Cited in Mayer. Dark Money.

[52] Lee Fang. “How John Birch Society Extremism Never Dies: The Fortune Behind Scott Walker’s Union-Busting Campaign.” ThinkProgress (February 21, 2011).

[53] Larissa MacFarquhar. “The Gilder Effect.” The New Yorker (May 29, 2000).

[54] Jude Wanniski. The Way the World Works: How Economies Fail—and Succeed (New York: Basic Books, 1978).

[55] Eric R. Wolf & Joseph G. Jorgensen. “A Special Supplement: Anthropology on the Warpath in Thailand.” New York Review of Books (November 19, 1970).

[56] Tucker, “A Closer Look at the Pioneer Fund: Response to Rushton.”