2. Ancient Greece

Phoenicians

Modern propaganda is founded on the idea that Western secular democracy represents the culmination of centuries of human intellectual evolution, which began in Ancient Greece. We are led to believe that Greek philosophy began our empiricist tradition, as the pursuit of objective truth, free of superstitions such as belief in the supernatural. Nothing could be further from the truth. F. M. Cornford, in From Religion to Philosophy, has set out to dispel the myth that Greek philosophy marked the birth of speculative thought, demonstrating that there was no radical break between the “age of religion” and the “age of philosophy.” Essentially, it represented contrived rationalizations formulated in an attempt to garner legitimacy for preconceived religious ideas. As Cornford points out: “the work of philosophy thus appears as the elucidation and clarifying of religious, or even pre-religious, material. It does not create its new conceptual tools; it rather discovers them by ever subtler analysis and closer definition of the elements confused in its original datum.”[1] More specifically, as Cornford pointed out, the theology that became the substance of Greek philosophy was not the worship of the pantheon inherited from Archaic times, but an entirely other creed, intended to topple the old belief system: the newly adopted teachings of the Chaldean Magi.

Contrary to popular assumptions, Greece was fundamentally a Middle Eastern Civilization. According to M.L. West, though a number of foreign elements were derived from other parts of the Near East, in Archaic times, it was the Semitic West specifically, composed of the land of the Canaanites and the Jews, which exercised the greatest degree of influence on Greek culture. As demonstrated in the Orientalizing Revolution, by professor Walter Burkert, recognized as perhaps the foremost scholar of Greek religion, the emergence from the Dark Age was brought about through cultural contact with Phoenicians, who were effectively indistinguishable from the Israelites, through intermarriage and a shared language and pagan cult.

The Phoenician influence on Ancient Greece was such that in The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, M.L. West, remarks that, “Near Eastern influence cannot be put down as a marginal phenomenon to be invoked occasionally in explanation of isolated peculiarities. It was pervasive at many levels and at most times.”[2] Burkert states that the impact on Greek art in this period is evident in imported objects as well as by new techniques and characteristic motifs of artistic imagery, though, the prejudices of modern scholars have led them to disregard the overwhelming evidence. He continues:

Even expert archaeologists, however, sometimes appear to feel uncomfortable about this fact and indeed advise against using the expression “the orientalizing period.” The foreign elements remain subject to a policy of containment: There is hardly a standard textbook that has oriental and Greek objects depicted side by side; many of the oriental finds in the great Greek sanctuaries have long remained, and some still remain, unpublished.[3]

The most important contribution of this interaction was the adoption by the Greeks of the Phoenician script. The Greeks did not begin to use letters for writing until about 700 BC, and only scraps have survived from before 600 BC. The Greeks borrowed their alphabet, with only slight innovations, from a letter system that had been used equally by Hebrews, Phoenicians and Aramaeans. The Greeks themselves called their alphabetic letters “Phoenician,” which had supposedly been introduced to them by Cadmus, a Phoenician prince. According to Greek mythology, Cadmus was the son of King Agenor and Queen Telephassa of Tyre and the brother of Phoenix (Phoenician), Cilix and Europa. He was originally sent by his royal parents to seek out and escort his sister Europa back to Tyre after she was abducted from the shores of Phoenicia by Zeus. Cadmus founded the Greek city of Thebes, the acropolis of which was originally named Cadmeia in his honour.

Hendrick Goltzius, Cadmus fighting the Dragon

In classical times, the Greeks recognized four great divisions among themselves, each named in honor of their respective ancestors: Achaeus of the Achaeans, Danaus of the Danaans, Cadmus of the Cadmeans (the Thebans), Hellen of the Hellenes (not to be confused with Helen of Troy), Aeolus of the Aeolians, Ion of the Ionians, and Dorus of the Dorians. Cadmus from Phoenicia, Danaus from Egypt, and Pelops from Anatolia each gained a foothold in mainland Greece and were assimilated and Hellenized. The Greeks were known as Hellenes, through their descent from Hellen, who along with her siblings, Graikos, Magnes, and Macedon were sons of Deucalion and Pyrrha, the only people who survived the Great Flood. Sons of Hellen and the nymph Orseis were Dorus, Xuthos, and Aeolus. Sons of Xuthos and Kreousa, daughter of Erechthea, were Ion and Achaeus.

The Ionians were descended from Cadmus and Danaus who were equated with the colonizers named Hyksos, a dynasty of foreign invaders who ruled a northern portion of Egypt, establishing themselves at a town called Abydos, but who were finally expelled by the Egyptians in 1450 BC, and eventually settled Palestine. Manetho, an Egyptian priest who lived around 250 BC, equated the Hyksos with the Jews of the Exodus. Hecataeus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the fourth century BC, set out his view of the traditions of the Egyptian expulsion of the Israelite Exodus and that of Danaus’ landing in Greece:

The natives of the land surmised that unless they removed the foreigners, their troubles would never be resolved. At once, therefore, the aliens were driven from the country and the most outstanding and active among them banded together and, as some say, were cast ashore in Greece and certain other regions; their leaders were notable men, among them being Danaus and Cadmus. But the greater number were driven into what is now called Judea, which is not far from Egypt and at that time was utterly uninhabited. The colony was headed by a man called Moses.[4]

The Abduction of Europa, the mother of King Minos of Crete, a Phoenician princess of Argive origin, after whom the continent Europe is named, by Rembrandt, 1632

The Dorians, who were said to have invaded Greece, were also believed to have been of Phoenician origin. The colonization of the Dorians conforms with the general upheavals that involved the dispersion of the Israelites. Scholars, therefore, recognize that the invasion of the Dorians may be connected with the devastation wrought by the controversial Sea Peoples referred to in Egyptian records, who also assaulted most of Palestine, Asia Minor and Greece in the twelfth century BC. The Danaans, descendants of Danaus, are usually identified with the Denyen Sea Peoples, as one of the twelve tribes of Israelites, the tribe of Dan, or the Danites. Yet, as Stager mentions in The Oxford History of the Biblical World:

Archaeologists agree that dramatic cultural change affected not only parts of Canaan but also much of the eastern Mediterranean at the end of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1200 BC). How much of that change was brought about by the migrations and/or invasions of newcomers to Canaan, and specifically by invading Israelites, is still an open question.[5]

The Sea Peoples shown being defeated at the hand of Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses III.

A number of sites counted among the conquests of the Sea Peoples are identical with those known to have been accomplished by the Israelites. As well, though such conquests are not recounted in the Bible, the Jews were also commanded to conquer all the lands of the Canaanites and their affiliated peoples, which included the Hittites known to have inhabited most of Asia Minor, or modern Turkey, and perhaps as far as Greece. The Trojan War may thus have been a conflict between the ancient Israelites from the Tribe of Dan, known to the Greeks as Danaans, or Denyen Sea Peoples, against Hittites, the native inhabitants of Asia Minor. In the Iliad, Homer refers to the Greeks as Achaeans, who were related to the Danaans descendants of Danaus, who was believed to be the son of Egyptian King Belus (Baal). The ancient city of Troy was located in the region known as the land of Troas, within which was also found, just several kilometers to the north, the city of Abydos, named after another city by the same name in Egypt, that had formerly been the capital of the Hyksos.

The Procession of the Trojan Horse into Troy by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (c. 1760)

The Dorians were also known as Heraklids being a claim, not only of descent from Hercules, but also to Phoenician ancestors. The Phoenician origin of Hercules is relatively undisputed, he being regarded as the equivalent of the Canaanite Melqart, another name for Baal. Hercules is obviously related to the Bible hero Samson, a story evidently included in the text through pagan or Kabbalistic influence. Samson and Hercules are both species of solar-heroes, identified with Orion, and derived from the Babylonian figure Gilgamesh, of the famous epic, who also killed an invincible lion and accomplished other great tasks. T.W. Doane, in Bible Myths and Their Parallels in Other Religions, has brought attention to the similarities that existed between Hercules and the story of Samson in the Old Testament. The two heroes were already compared in antiquity by Eusebius, St. Augustine and Filastrius. Samson, derived from Shamash, the Babylonian Sun-god, is the solar-hero of the Bible, his name meaning “belonging to the Sun.”[6]

Likewise, according to Herodotus, “if we trace the ancestry of the Danae, the daughter of Acrisius, we find that the Dorian chieftains are genuine Egyptians. This is the accepted Greek version of the genealogy of the Spartan royal house… But there is no need to pursue this subject further. How it happened that Egyptians came to the Peloponnese, and what they did to make themselves kings in that part of Greece, has been chronicled by other writers.”[7] In Greek mythology, the Spartoi are a mythical people who sprang up from the dragon's teeth sown by Cadmus and were believed to be the ancestors of the Theban nobility. The other half of the dragon's teeth were planted by Jason at Colchis.

It may have been on this basis that, sometime around 300 BC, Areios, King of Sparta, wrote to Jerusalem: “To Onias High Priest, greeting. A document has come to light which shows that the Spartans and Jews are kinsmen descended alike from Abraham.”[8] Both books of Maccabees of the Apocrypha mention a link between the Spartans and Jews. Maccabees 2 speaks of certain Jews “having embarked to go to the Lacedaemonians (Spartans), in hope of finding protection there because of their kinship.” In Maccabees 1, “It has been found in writing concerning the Spartans and the Jews that they are brethren and are of the family of Abraham.”[9]

Orpheus

Orpheus in the Underworld by Frans Francken the Younger (c. 1660)

Orphic Egg (Jacob Bryant, 1774)

Following their release from the Captivity in Babylon, not all Jews returned to Jerusalem however. Some remained in Babylon, while others followed the conquests of the Persians and settled in Egypt and Greece, where they contributed to the rise of Greek philosophy. On the authority of Bardesanes, a Syrian Christian of the late first and early second century AD, the Magussaeans, wherever they were found, observed “the laws of their forefathers, and the initiatory rites of their mysteries.”[10] Among the rumors associated with these mysteries was the practice of human sacrifice.

Herodotus maintained the Near Eastern origin of the phallic rites of the Greek Dionysus, attributing its importation to Melampus, who got his knowledge about Dionysus through Cadmus.[11] The legendary founder of the rites of Dionysus was known to have been Orpheus, who inspired the Orphic movement, which was influenced by Zurvanism.[12] In the Orphic tradition, it was Chronos, the equivalent of Zurvan, who governed chronological time Aether and Chaos, and an egg, from which Phanes was born.[13]

The founding literature of the Greek mysteries were the poems of Orpheus and Musaeus, written, or at least redacted, by the notorious forger, Onomacritus. Orpheus was a legendary figure, the son of a Muse and the king of Thrace. He joined the expedition of the Argonauts, saving them from the music of the Sirens by playing his own, which was so powerful that even animals, trees and rocks began to dance. When, upon his return, his wife Eurydice was killed by a snakebite, Orpheus went down into to Hades, the Underworld, to bring her back. With his singing and lyre playing, he charmed Charon, the ferryman of the River Styx, and the triple-headed dog Cerberus, who guarded the palace of Pluto. His music and grief so moved Pluto and Persephone, the king and the queen of Hades, that they allowed him to take back Eurydice.

Orpheus wearing a Phrygian cap surrounded by animals (Ancient Roman floor mosaic, from Palermo, now in the Museo archeologico regionale di Palermo)

Among the Greeks, Orpheus was regarded as a foreigner, having come from Thrace, the region of the southeastern Balkans, most of which had become subject to Persia about 516-510 BC. Though, Pliny remarked: “I would have said that Orpheus was the first to import magic to his native land from abroad and that superstition evolved from medicine, if the whole of Thrace had not been free of magic.”[14] According to Strabo, Orpheus was a “magician who at first was a wandering musician and soothsayer and peddler of the rites of initiation.”[15] Plato stated:

Beggar priests and seers come to the doors of the rich and convince them that in their hands, given by the gods, there lies the power to heal with sacrifices and incantations, if a misdeed has been committed by themselves or their ancestors, with pleasurable festivals… and they offer a bundle of books of Musaeus and Orpheus… according to which they perform their sacrifices; they persuade not only individuals but whole cities that there is release and purification from sin through sacrifices and playful pastimes, and indeed for both the living and the dead; they call these teletai, which deliver us from evil in the afterlife; anyone who declines to sacrifice, however, is told that terrible things are waiting for him.[16]

Aristobulus, a third century BC Jewish philosopher, claimed that Orpheus was a follower of Moses, and quoted the following from an Orphic poem: “I will sing for those for whom it is lawful, but you uninitiate, close your doors, charged under the laws of the Righteous ones, for the Divine has legislated for all alike. But you, son of the light-bearing moon, Musaeus (Moses), listen, for I proclaim the Truth…”[17] Artapanus, third century BC Jewish philosopher, declared of Moses that, “as a grown man he was called Musaeus by the Greeks. This Musaeus was the teacher of Orpheus.”[18]

Part of the Orphic ritual is thought to have involved the mimed or actual dismemberment of an individual, representing the god Dionysus, who was then said to have been reborn. The female worshippers of Bacchus, called Maenads, were supposed to re-enact the tearing and eating of Dionysus by the Titans, by whipping themselves into a frenzy, and tearing a live bull to pieces with their bare hands and teeth, for the animal in some sense was an incarnation of the god.[19] Several descriptions of the rites of the Dionysians are available from ancient authors. Clement of Alexandria reports:

The raving Dionysus is worshipped by Bacchants with orgies, in which they celebrate their sacred frenzy by a feast of raw flesh. Wreathed with snakes, they perform the distribution of portions of their victims, shouting the name of Eva (Eua), that Eva through whom error entered into the world; and a consecrated snake is the emblem of the Bacchic orgies.[20]

Orpheus and the Bacchantes by Gregorio Lazzarini (circa 1655)

The Dionysiac rites appear to derive from necromancy, the art of summoning the spirits of the Underworld, or black magic, of daeva worshipping Magi. Heraclitus, a Greek philosopher of the sixth century BC, equated the rites of the Bacchants with those of the Magi, and commented: “if it were not for Dionysus that they hold processions and sing hymns to the shameful parts [phalli], it would be a most shameless act; but Hades and Dionysus are the same, in whose honor they go mad and celebrate the Bacchic rites,”[21] and of the “Nightwalkers, Magi, Bacchoi, Lenai, and the initiated,” all these people he threatens with what happens after death: “for the secret rites practiced among humans are celebrated in an unholy manner.”[22] In a papyrus from Derveni, near Thessaloniki, belonging to the fourth century BC, we read about “incantations” of the Magoi that are able to “placate daimones who could bring disorder… Therefore, the magoi perform this sacrifice as if they would pay an amend,” and initiates of Dionysus, “first sacrifice to the Eumenides, like the magoi.” In Magic and the Ancient World, Fritz Graf, Professor of Classics at Princeton University, remarks:

Not only does the unknown author connect the rites of the magi with those of the mystery cults (a topic which becomes fundamental with the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri), but also he introduces the magoi as invokers of infernal powers, daimones whom he understands as the souls of the dead, the disorder that they bring manifests itself in illness and madness, which are healed by rituals of exorcism.[23]

The practice of human sacrifice in the rites of Dionysus is alluded to in Euripides’ play The Bacchae. It premiered posthumously at the Theatre of Dionysus in 405 BC and won first prize in the City Dionysia festival competition. The tragedy is based on the Greek myth of King Pentheus of Thebes and his mother Agave, and their punishment by Pentheus’ cousin, the god Dionysus. Dionysus appears at the beginning of the play and proclaims that he has arrived in Thebes to avenge the slander, which has been repeated by his aunts, that he is not the son of Zeus. In response, he intends to introduce Dionysian rites into the city, to demonstrate to Pentheus and to Thebes that he was indeed born a god. In one scene guards sent to control the Maenads witness them pulling a live bull to pieces with their hands. Later, after Pentheus has banned the worship of Dionysus, the god lures him into a forest, to be torn limb from limb by Maenads, including his own mother Agave. At the end of the play, Agave bears Pentheus’ head on a pike to her father Cadmus.

Mysteries of Eleusis

Phryne on the Poseidon's celebration in Eleusis by Nikolay Pavlenko (1894)

The emergence of the mystery cults in the sixth century BC, the most famous of which were the Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter, represented a fundamental aspect of the transformation of Greek religion. The Eleusinian Mysteries, like the Thesmophoria, an autumn agricultural festival that was exclusively for women, celebrated the fertility of grain, in the manner of early fertility rites practiced throughout the ancient Middle East. Nevertheless, some have sought to attribute their propagation in Greece to a hypothetical “shamanistic tradition” issuing from the “north.” Joseph Campbell, the noted scholar of comparative religion, believed:

The Aryans entering Greece, Anatolia, Persia, and the Gangetic plain c. 1500-1250 BC, brought with them... the comparatively primitive mythologies of their patriarchal pantheons, which in creative consort with the earlier mythologies of the Universal Goddess generated in India the Vedantic, Puranic, Tantric, and Buddhist doctrines, and in Greece those of Homer and Hesiod, Greek tragedy and philosophy, the Mysteries, and Greek science.[24]

However, rituals similar to those of Eleusis were characteristic of many centers of ancient eastern Mediterranean civilizations, including islands as far north as Samothrace, as far east as Cyprus, and as far south as Crete. In all of these regions were cults of one or another Great Goddess of fertility and the harvest, whose worship involved secret rites of purification and initiation. As far back as the seventh century BC, on the west coast of Asia Minor, Greek city-states worshipped the Phrygian goddess Cybele, known as the Magna Mater, which was taken over from the Persian worship of Anahita (Persian Athena) in Cappadocia, now east-central Turkey.

According to Diodorus of Sicily, “Isis was transferred by the Greeks to Argos, while in their mythology they said that she was Io, who was transformed into a cow, but some think the same deity to be Isis, some Demeter, some Thesmophorus, but others Selene, and others Hera.”[25] And, Herodotus attributed the introduction of the Mysteries of Eleusis to the Danaans:

I propose to hold my tongue about the mysterious rites of Demeter, which the Greeks call Thesmophoria, though… I may say, for instance, that it was the daughters of Danaus who brought this ceremony from Egypt and instructed the Pelasgian women in it, and that after the Dorian conquest of the Peloponnese it was lost; only the Arcadians, who were not driven from their homes by the invaders, continued the celebration of it.[26]

A possible source of the myth of the Eleusinian mysteries may have been reproduced in Homer’s Hymn to Demeter. Here Hades is said to have come forth from the Underworld in his chariot to seize Persephone, the daughter of Demeter and Zeus. Demeter leaves Olympus in search of her daughter, roaming the earth disguising herself as an old woman. By the Maiden Well in Eleusis, she met the daughters of King Keleus, who offered her the position of nurse to their newly born brother Demophoon.

At the palace Demeter nursed Demophoon who grew like an immortal being. She fed him with ambrosia and, secretly at night, probably as an allusion to child sacrifice, hid him in the midst of the fire without burning him. One night, the child’s mother Metaneira, caught Demeter holding the child in the fire, and yelled in horror, thus preventing him from gaining immortality. Demeter returned to her original form, and in her continuing grief, caused a famine, that would have destroyed mankind, until Zeus sent Hermes, the messenger of the gods, down to Hades to request Persephone. Hades acquiesced, but through a ploy, deceived Persephone into marrying him. Consequently, Persephone would have to dwell with Hades for a third of the year, becoming goddess of the Underworld, coming forth in spring, when she made the earth bloom again and taught her mysteries to the Eleusinians.

Walter Burkert has pointed to the evident Middle Eastern fertility motifs present in the Hymn to Demeter, and according to Penglase, in Greek Myths and Mesopotamia:

The hymn is outstanding for the striking number and the nature of the parallels with Mesopotamian myths. Indeed, numerous motifs and underlying ideas are not only closely similar but are complex features central to the Mesopotamian myths as they are to the Greek hymn. Just as significantly, they are also found in a specific group of Mesopotamian myths, that is, among the myths of the goddess-and-consort strand representing the cult of Inanna and her consort Dumuzi, and of Damu, who is identified with him. There are many parallels, especially in the central structural ideas of the journeys carried out by the gods and in the accompanying idea of the power involved in the journey, but there are also striking parallels of motif with similar underlying ideas; so many, in fact, that the conclusion of Mesopotamian influence, is, even at first sight, hard to avoid, and on closer inspection, compelling.[27]

The word mystery, mysterion in Greek, derives from the Greek verb mystein, “to close,” referring to the closed secrecy of the rituals, because an initiate was required to keep silent about that which was revealed to him in the private ceremony. The priests in the mysteries were called hierophantes, hierophants, “one who shows sacred things.” The highest stage of initiation in the Eleusinian mysteries is that of epopteia, “beholding,” and an initiate into the great mysteries was called an epoptes, “beholder.” Although there were festivals of Demeter practiced throughout Greece, the true Eleusinian Mysteries were celebrated at Eleusis only. This was changed when Eleusis was annexed to the Athenian territory about 600 BC. The first hall of initiations for the mysteries of Demeter and Kore, was built in the time of the tyrant Peisistratus. Every Athenian was admitted to the Eleusinian mysteries, and soon the mysteries were open to every Greek.

Because mysteries refer to secret rites and ceremonies, of a meaning and significance known only to the initiated, what occurred at rites practiced at Eleusis generally remains unknown. It is commonly thought that a betrayal of the pledge of silence was the main concern in the case of the Athenian leader Alcibiades during the late fifth century BC. In Plutarch’s Life of Alcibiades, it is said that Alcibiades and his friends were accused of having profaned the Eleusinian mysteries in a drunken parody of the ritual. Several of them mimicked the roles of the officials in the rites, while the rest pretended to be initiates, and were later called to face charges of impiety for both profaning the mysteries and mutilating of the phallic images of Hermes.[28]

The mysteries began with the march of the initiates, mystai, in solemn procession from Athens to Eleusis. The rites that they then performed in the Telesterion, or Hall of Initiation, were and remain a secret. It is clear, however, that neophytes were initiated in stages, and that the annual process began with purification rites called the Lesser Mysteries. The Greater Mysteries at Eleusis was celebrated annually. It included a ritual bath in the sea, three days of fasting, and completion of the still-mysterious central rite. These acts completed the initiation, and the initiate was promised benefits in the world to come. A fragment of Pindar, quoted by Clement of Alexandria, elucidates the ultimate significance of the myth of the descent into the Underworld dramatically enacted by the initiate: “Blessed is one who goes under the earth after seeing these things. That person knows the end of life, and knows its Zeus-given beginning.”[29]

Greek Philosophy

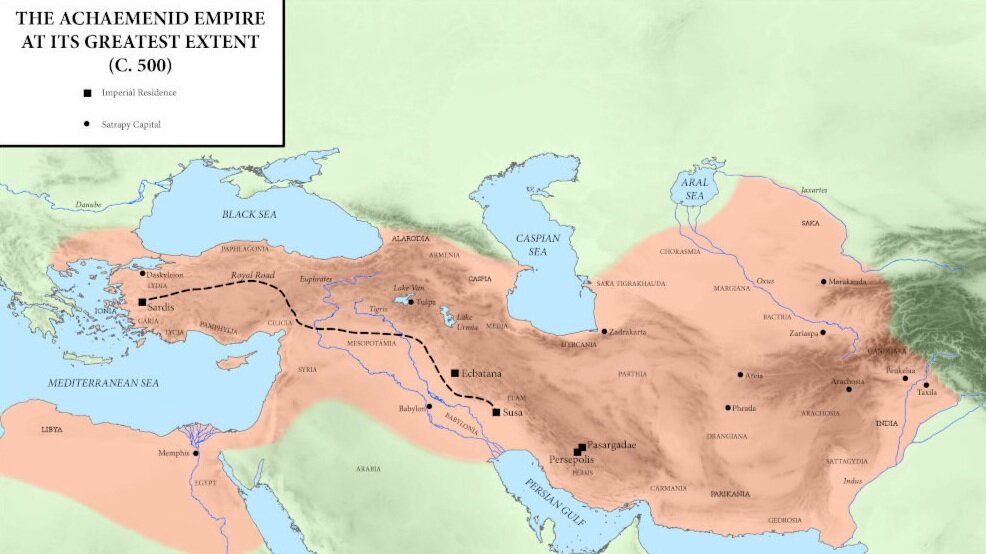

Throughout the classical period, ancient Greece was merely a collection of small rivaling city-states, while the Persians erected an empire that, at its height, spanned an immense territory, including the whole of the Middle East, Egypt, parts of India, Armenia, Afghanistan, Turkestan, Asia Minor and Thrace. Towards the middle of the sixth century BC, Western Asia was divided into three kingdoms: the Babylonian Empire, Media, now northwestern Iran, and Lydia, which comprised northwestern Asia Minor. After seizing control of the Median Empire, Cyrus invaded Assyria and Babylonia in 549 BC. In 546 BC, he attacked Croesus of Lydia, defeated him, and annexed Asia Minor to his realm, followed by the gradual conquest of the small Greek city-states along the coast. Cyrus then conquered Bactriana, and in 539 BC, marched against Babylon.

Cyrus’ son Cambyses, added Egypt in 525 BC, and after him, in 522, Darius came to power and set about consolidating and strengthening the Persian empire. From 521 to 484 BC, Darius expanded the empire further with conquests in India, Central Asia and European Thrace. Darius did not achieve all that he wished though his work rivaled that of Cyrus. The empire was decentralized, divided into twenty provinces, each under a satrap who was a royal prince or great nobleman. Royal inspectors surveyed their work and their control over administration made easier by the institution of a royal secretariat to conduct correspondence with the provinces. Aramaic, the old language of the Assyrians, was adopted as the official language, well adapted to imperial affairs because it was not written in cuneiform, but in the Phoenician script.

Contact between Greeks and the Magi resulted from the Persian conquest of the Greek city-states of Ionia in Asia Minor. Beginning in the sixth century BC, Ionia came under Persian domination, and for the most part, would not achieve independence until the time of Alexander in the fourth century BC. Therefore, as Greek philosophy emerged in a region of the world that was then part of the Persian Empire, it should not be regarded as a Greek phenomenon at all. Though Greek speaking, most of the first philosophers, referred to collectively as Pre-Socratics, were from Ionia.

In Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient, M.L. West has suggested that the introduction of Persian and Babylonian beliefs into Greece was attributable to Magi fleeing west from Cyrus’ annexation of Media. In Alien Wisdom, Arnaldo Momigliano affirms:

Those who have maintained that Pherecydes of Syros, Anaximander, Heraclitus and even Empedocles derived some of their doctrines from Persia have not always been aware that the political situation was favourable to such contacts. But this cannot be said of Professor M. L. West, the latest supporter of the Iranian origins of Greek philosophy. He certainly knows that if there was a time in which the Magi could export their theories to a Greek world ready to listen, it was the second half of the sixth century BC. It is undeniably tempting to explain certain features of early Greek philosophy by Iranian influences. The sudden elevation of Time to a primeval god in Pherecydes, the identification of Fire with Justice in Heraclitus, Anaximander’s astronomy placing the stars nearer to the Earth than the moon, these and other ideas immediately call to mind theories which we have been taught to consider Zoroastrian, or at any rate Persian, or at least Oriental.[30]

Therefore, among the Pre-Socratics, we find a concern with the typical Magian doctrines of astralism, dualism, and pantheism. Thus, the earliest of the Pre-Socratics contended as to which of the four elements was the underlying substance of the universe. Anaximander of Miletus, who was sixty-four years old in 547 or 546 BC, and pupil of Thales, speculated that the sky contained separate spheres through which the planets traveled, a concept that would dominate astronomical thought until the seventeenth century. Thales had believed that the underlying substance of the universe was water, but Anaximander thought it to be something other, and that it was boundless, from which the four elements ensue. Like Anaximander, Anaximenes, who flourished in 545 BC, the third Milesian among those regarded as the first of the Greek philosophers, believed that the underlying matter is boundless, but consisting of air, which he regarded as a god. As it becomes denser, air becomes fire, water and earth.

Magian thought is again evident in Anaxagoras, who was born in Ionia around 500 BC, was the teacher of both the statesman Pericles and the playwright Euripedes, and the greatest influence on the philosopher Socrates. He had been summoned to trial for teaching astronomy and for being pro-Persian. He explained: “and Mind set in order all things, whatever kinds of things were to be, whatever were and all that are now and whatever will be, and also this rotation in which are now rotating the stars and the Sun and the moon, and the air and aither that are being separated off.”[31] To Heraclitus, born in the Ionian city of Ephesus about 540 BC, in accordance with the teachings of the Magi, God was a fire endowed with intelligence. As with most, if not all, of the early philosophers, Heraclitus espoused a doctrine of pantheism, the belief that the entire universe is a single eternal living being.

Nearly all Presocratic philosophers adhered to a dualistic philosophy of the universe, seeing the world as a struggle between opposites. The Pythagoreans “…posited two principles,”[32] and to Anaximander (c. 610 – c. 546 BC), Justice regulates the interplay of physical opposites. To Empedocles all things consist of fire, and he envisaged a dualistic universe, and of great cosmic cycles in which the four elements, earth, air, fire and water, are mixed together by Love and pulled apart by Strife. Empedocles discusses an account of a descent and return from the underworld paralleled by Lucian’s mention of the practices of a Zoroastrian Magus at Babylon, who he, “…heard are able, through certain spells and rituals, to open the gates of Hades and take down safely whomever they want and then bring them back up again.”[33] Empedocles was born about 515 BC, in Elea in southern Italy, a famous center of Greek philosophy, which owned its existence to the Persian takeover of Ionia in 546 BC. Several ancient writers, including Pliny, Philostratus and Apulaeus had made Empedocles a disciple of the Magi, and the first reference we have of him in surviving Greek literature, dating back to his own lifetime, is from the fifth century BC, Xanthus of Lydia, which presented him in the context of a discussion of the Persian Magi.[34]

Osthanes, Zoroaster’s supposed disciple, known as the “prince of the Magi,” was said to have accompanied Xerxes on his campaign against Greece as his chief magus. Pliny mentioned that Osthanes was the first person to write a book on magic “and nurtured the seeds, as it were, of this monstrous art, spreading the disease to all corners of the world on his way. However, some very thorough researchers place another Zoroaster, who came from Proconnesus, somewhat before Osthanes’ time. One thing is certain. Osthanes was chiefly responsible for stirring up among the Greeks not merely an appetite but a mad obsession for this art.”[35]

It is said that after the emperor’s defeat at Salamis, Osthanes stayed behind to become the teacher of Democritus, an Ionian philosopher, born in 460 BC. The reputed author of seventy-two works, Democritus apparently also visited Babylon to study the science of the Chaldeans, of which he is to have written on the subject. He summed up his results of his investigations in a Chaldean Treatise, another tractate was entitled On the Sacred Writings of Those in Babylon, and as a result of his visit to Persia, he wrote Mageia. In an extract, Democritus, following the Babylonian pattern, distinguishes the trinity of the Sun, Moon and Venus from the other planets.[36]

Plato

The School of Athens by Raphael (1509–1511) with Plato and Aristotle (center) and Zoroaster (right facing, holding globe)

Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BC)

Greeks may have also absorbed Magian tenets through their extensive contacts with the Egyptians. Herodotus recounted that, “during the reign of Cambyses in Egypt, a great many Greeks visited that country for one reason or another: some, as was to be expected, for trade, some to serve in the army, others, no doubt, out of mere curiosity, to see what they could see.”[37] As Diodorus explained:

But now that we have examined these matters we must enumerate what Greeks, who have won fame for their wisdom and learning, visited Egypt in ancient times in order to become acquainted with its customs and learning. For the priests of Egypt recount from the records of their sacred books that they were visited in early times by Orpheus, Musaeus, Melampus, and Daedalus, also by the poet Homer and Lycurgus of Sparta, later by Solon of Athens and the philosopher Plato, and that there came also Pythagoras of Samos and the mathematician Eudoxus, as well as Democritus of Abdera and Oenopides of Chios. As evidence for the visits of all these men they point in some cases to their statues and in others to places or buildings which bear their names, and they offer proofs from the branch of learning which each one of these men pursued, arguing that all the things for which they were admired among the Greeks were borrowed from Egypt.[38]

Though Pythagoras was born on the island of Samos, his father was a Phoenician from Tyre.[39] Pythagoras had traveled to Egypt, at which point, according to Apuleius in his Apology, he was captured by Cambyses during his invasion of the country and taken back to Babylon along with other prisoners. In Babylon, maintains Porphyry, Pythagoras was taught by Zaratas, a disciple of Zoroaster, and initiated into the highest esoteric mysteries of the Zoroastrians.[40] According to Iamblichus, Pythagoras traveled to Phoenicia, where “he conversed with the prophets who were descendants of Moschus (Moses) the physiologist, and with many others, as well as with the local hierophants.[41] The ancient Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37 – c. 100) also believed in Pythagoras’ affinity for Jewish ideas: “Now it is plain that he did not only know our doctrines, but was in very great measure a follower and admirer of them… For it is very truly affirmed of this Pythagoras, that he took a great many of the laws of the Jews into his own philosophy.”[42]

According to F.M. Cornford, “whether or not we accept the hypothesis of direct influence from Persia on the Ionian Greeks in the sixth century, any student of Orphic and Pythagorean thought cannot fail to see that the similarities between it and Persian religion are so close as to warrant our regarding them as expressions of the same view of life, and using the one system to interpret the other.”[43] As Bertrand Russell outlined, “from Pythagoras, Orphic elements entered into the philosophy of Plato, and from Plato into most later philosophy that was in any degree religious.”[44]

According to Momigliano, “it was Plato who made Persian wisdom thoroughly fashionable, though the exact place of Plato in the story is ambiguous and paradoxical.”[45] In antiquity, the reputation of Plato’s purported connection with the Magi was widespread. Plato’s only actual mention of Zoroaster, though, is found in the Alcibiades—which may or may not have been his work—in which Socrates states that the Babylonians, who educate their children in “the Magian lore of Zoroaster, son of Ahura Mazda,” are superior to those in Athens.[46] Yet, according to Diogenes Laertius, Plato’s teacher Socrates met a magus who made a number of predictions, including that of Socrates’ death. Plato himself is said to have spent several years in Egypt, after which he had intended to visit the Magi, but was prevented due to the wars with Persia.[47] Nevertheless, in a manuscript found in the ruins of Herculaneum, which was destroyed along with Pompeii in the eruption of Vesuvius, Plato is said to have met with a Chaldean shortly before his death. Finally, the Epicurean Colotes mocked Plato’s purported borrowings from Zoroaster, which indicates that this connection was a well established opinion around 280-250 BC.[48]

Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 390? – c. 337 BC)

The man considered responsible for introducing Magian tenets to Plato was one of his friends, an Ionian mathematician and astronomer, Eudoxus of Cnidus, who seems to have acted as head of the Academy during Plato’s absence. Eudoxus is said to have traveled to Babylon and Egypt, studying at Heliopolis, where he learned the priestly wisdom and astronomy. According to Pliny, Eudoxus “wished magic to be recognized as the most noble and useful of the schools of philosophy.”[49] As well, according to Aristobulus, a third century BC Jewish philosopher, Plato also had access to translations of Jewish texts, and therefore, “it is evident that Plato imitated our legislation and that he had investigated thoroughly each of the elements in it… For he was very learned, as was Pythagoras, who transferred many of our doctrines and integrated them into his own beliefs.”[50] Numenius of Apamea, of the late second century AD, remarked, “what is Plato, but Moses speaking in Attic Greek.”[51]

Plato’s Spindle of Necessity

The great exposition of Magian thought in the Greek language is the Timaeus, where Plato treated the common Magian themes of Time, triads, pantheism, astrology, and the four elements. The purpose of life, according to the Timaeus, is to study the heavens. Most common to the tales or motifs borrowed from the Magi were those dealing with visits to the Underworld. Plato provides his description of the ideal state in The Republic, proposing a stratified society based on three classes, including guardians, also known as philosopher kings, followed by a warrior class and then producers below them. To explain how guardians are to be instructed, Plato presents the “Myth of Er,” which holds many parallels with occult and later Kabbalistic doctrines. The story consists of a vision of the afterlife recounted by Er, the son of Armenius [Armenian], who died in a war but returned to life to act as a messenger from the other world. He described a heaven and hell where souls are either rewarded or punished, and a cosmic vision of the universe, controlled by the Spindle of Necessity and her daughters, the three Fates, where the Sirens’ song echoed the harmony of the seven spheres.

Colotes, a philosopher of the third century BC, accused Plato of plagiarism, maintaining that he substituted Er’s name for that of Zoroaster. The myth’s similarity with Chaldean ideas is confirmed in that in it Plato presents a list of colors corresponding to each of the planets which conforms precisely with the correspondence offered in Babylonian texts.[52] Clement of Alexandria and Proclus quote from a work entitled On Nature, attributed to Zoroaster in which he is equated with Er.[53] Quoting the opening of the work, Clement mentions:

Zoroaster, then, writes: “These things I wrote, I Zoroaster, the son of Armenius, a Pamphylian by birth: having died in battle, and been in Hades, I learned them of the gods.” This Zoroaster, Plato says, having been placed on the funeral pyre, rose again to life in twelve days. He alludes perchance to the resurrection, or perchance to the fact that the path for souls to ascension lies through the twelve signs of the zodiac; and he himself says, that the descending pathway to birth is the same. In the same way we are to understand the twelve labours of Hercules, after which the soul obtains release from this entire world.[54]

Finally, in the Timaeus and the Critias, Plato set out the myth of Atlantis. Plato records the conversations Socrates had with Timaeus, Hermocrates and Critias. Responding to a request from Socrates for a historical example of an ideal state, Critias describes an account of Atlantis, inherited from his grandfather, written by the Athenian poet and lawgiver Solon who lived between 638 and 558 BC. This story was narrated to him while visiting Egypt, by a priest who interpreted for him the hieroglyphic script on a pillar in the Temple of Neith. He was told:

There once existed beyond the strait you call the Pillars of Hercules an island, larger than Asia and Libya together, from where it was still possible at that time to sail to another island and from there to the continent beyond them which enclosed the sea named after it… on this island of Atlantis there existed a great and estimable kingdom, which had acquired dominion of the entire island, as well as of the other island part of the continent itself.[55]

The priest told Solon that Athena had founded a great Athenian empire 9000 years earlier which was attacked by the Atlanteans who, not satisfied with ruling their own islands, tried to conquer the whole Mediterranean. They established their rule over Egypt and Tuscany but were defeated by the Athenians. Then a great earthquake and flood devastated Athens, drowning the Athenian army, and causing Atlantis to sink below the Atlantic Ocean.

Divine Madness

It was also Plato who articulated an early rationalization for pedophilia by linking it to his concept of “divine madness.” In Ancient Greece, pederasty was a romantic relationship socially acknowledged in ancient Greece between an erastes (“older male”) and an eromenos (“teenage male”). According to Plato, “there are two kinds of madness, one caused by human illnesses, the other by a divine release from the norms of conventional behaviour.”[56] This second form of madness is associated with what is believed to be ecstatic or trance states associated with mysticism, or more accurately, demonic possession, as was the case with the Maenads. According to Plato’s Symposium, through the mouth of Diotima, “It is by means of spirits that all divination can take place, the whole craft of seers and priests, with their sacrifices, rites and spells, and all prophecy and magic.”[57] As Plato explained, “If madness were simply an evil, it would be right, but in fact some of our greatest blessings come from madness, when it is granted to us as a divine gift.”[58] As examples, Plato lists the oracles of Delphi and Dodona. Plato also mentions the Sibyl and other prophetesses, “who, when possessed by a god, use prophecy to predict the future and have on numerous occasions pointed a lot of people in the right direction.”[59] Plato listed four types of divine madness, each with its own deity: prophetic inspiration from Apollo, mystical inspiration from Dionysus, poetic inspiration from the Muses, and finally from Aphrodite and Eros, “the god responsible for beautiful boys.”[60]

Erotic mania is one of the main topics of the Phaedrus. Socrates first agrees with his young friend Phaedrus reading the speech composed by the orator Lysias who claimed that true lovers were mad and were a detriment to society. However, later in the work, Socrates is given a sign by his daimonion, and heard a voice demanding that he repent. Describing himself as a mantis (“seer”), Socrates says that he immediately understood his error and offers a retraction.[61] Here, Plato employs the analogy of the horse-drawn chariot to describe the competing inclinations of the soul, the one recoiling from the scandalous perversion of sex with a male child and the other one aroused and indulgent. The horses are tamed and the soul aspires the higher philosophical truths through contemplation of the beauty of the boy, who is adored as a god. According to Plato:

When a man by the right method of boy-loving ascends from these particulars and begins to descry that beauty, he is almost able to lay hold of the final secret… From personal beauty he proceeds to beautiful observances, from observance to beautiful learning, and from learning at last to that particular study which is concerned with the beautiful itself and that alone; so that at the end he comes to know the very essence of beauty. In that state of life among all others… a man finds it truly worthwhile to live, as he contemplates essential beauty.[62]

Thus, “the most fundamental experience of beauty,” according to Plato, as explained by Yulia Ustinova, in Divine Mania Alteration of Consciousness in Ancient Greece, “is the pleasure a man takes in seeing a handsome youth, and from this we can infer that aesthetic education in the Republic is still focused on the beauty of the male body.”[63] The Republic provided the basis for modern fascist projects, including the elimination of marriage and the family, compulsory education, the use of eugenics by the state, and the employment of deceptive propaganda methods. According to Plato, “all these women shall be wives in common to all the men, and not one of them shall live privately with any man; the children too should be held in common so that no parent shall know which is his own offspring, and no child shall know his parent”[64] This belief is associated with a need for eugenics, as “the best men must cohabit with the best women in as many cases as possible and the worst with the worst in the fewest, and that the offspring of the one must be reared and that of the other not, if the flock is to be as perfect as possible.” More pernicious still is his prescription for infanticide: “The offspring of the inferior, and any of those of the other sort who are born defective, they will properly dispose of in secret, so that no one will know what has become of them. That is the condition of preserving the purity of the guardians’ breed.”

Compulsory schooling is to be implemented in order to separate children from their parents, to have them indoctrinated in the ideals of the state:

They [philosopher-kings] will begin by sending out into the country all the inhabitants of the city who are more than ten years old, and will take possession of their children, who will be unaffected by the habits of their parents; these they will train in their own habits and laws, I mean in the laws which we have given them: and in this way the State and constitution of which we were speaking will soonest and most easily attain happiness, and the nation which has such a constitution will gain most.[65]

Plato also articulated the concept of the “noble lie.” As for propaganda, according to Plato, “Our rulers will find a considerable dose of falsehood and deceit necessary for the good of their subjects.” He further explains, “Rhetoric… is a producer of persuasion for belief, not for instruction in the matter of right and wrong. And so the rhetorician’s business is not to instruct a law court or a public meeting in matters of right and wrong, but only to make them believe; since, I take it, he could not in a short while instruct such a mass of people in matters so important.”[66]

In the “Parable of the Cave” of the Republic, Plato makes use of the image of a cave, in which shadows of objects are cast by a fire onto a wall. Men enchained in the cave cannot turn their heads to see the fire or the objects, and know only their projected images. The allegory is designed to explain the prison of illusion within which humans are generally trapped. If fortunate to be released from his shackles, that is, initiated, the philosopher may recognize that what he had thought was real were mere shadows of props projected by a false light. He may then begin the ascent upward to the entrance of the cave, to gaze at the true light, or true knowledge, symbolized by the Sun, as the Mithraists, who seek union with Mithras, the Sun.

Great Year

Plato used the term “perfect year” to describe the return of the planets and the diurnal rotation of the fixed stars to their original positions, a phenomenon associated with the precession of the equinoxes. As the Earth rotates on its own axis, such that the sun rises over time in different constellations, resulting in a Great Year, which scientific astronomy defines as the period of one complete cycle of the equinoxes around the circle of the zodiac, or about 25,800 years. The Sun thus rises during the Spring Equinox in a different constellation approximately every 2,000 years, such that we are perceived to be currently in the Age of Pisces, and on the verge or having already entered the Age of Aquarius. However, there is supposedly no evidence Plato had any knowledge of axial precession. The cycle which Plato describes is one of planetary and astral conjunction, which can be postulated without any awareness of axial precession. Instead, the discovery of the phenomenon is attributed to Hipparchus (c. 120 BC), roughly two hundred years after Plato’s death. However, in the twentieth century, additional evidence from Greek and Babylonian sources now support that Kidinnu or Kidenas, of the fourth-century BC, known to the Greeks as Cidenas, a Chaldean astronomer who was head of the astronomical school in Sippar, appears to have discovered the phenomenon before Hipparchus.[67]

In the Timaeus, Plato described a conflagration of the world by fire which connected the myth of the chariot of Phaethon with the Great Year. According to the Greek version of the myth, Helios reluctantly grants permission to his son Phaethon to drive the chariot of the Sun across the sky. Being unable to guide the Sun’s chariot, Phaethon scorches a part of the earth. According to Plato, when Solon inquired of it among the Egyptians, they explained to him that the myth actually refers to the fact that “there is at long intervals a variation in the course of the heavenly bodies and a consequent widespread destruction by fire of things on the earth.”[68]

Phaethon on the Chariot of Apollo by Nicolas Bertin (1720)

Recalling the ascent of Mithras to heaven in a chariot, in the Phaedrus, Plato offers an analogy of the soul, comparing it again to a chariot drawn by two horses, a myth which held particular importance for later philosophers and mystics, interpreted along with Timaeus, as an account of the celestial ascent of the soul and its subsequent fall. In the Phaedrus, Plato describes the soul’s ascent to the border of heaven, where Zeus, holding the reins of a winged chariot, leads the way in heaven, ordering all and taking care of all. Presumably referring to the twelve constellations, Zeus is followed by “the array of gods and demigods, marshaled in eleven bands; Hestia alone abides at home in the house of heaven; of the rest they who are reckoned among the princely twelve march in their appointed order.” Plato then puts forth the image of the soul, imparted with wings under the influence of divine love, which expresses and experiences this love according to the astrological nature of the god, or constellation, it followed in heaven. Thus, for example, the attendants of Ares, the god of war and the planet Mars, “if they fancy that they have been at all wronged, are ready to kill and put an end to themselves and their beloved.”[69]

Dio Chrysostom recorded a hymn sung by the Magi of Asia Minor on account of its resemblance to the Stoic theory of conflagrations. In the hymn, which Dio claimed was “sung by Zoroaster and the children of the Magi who learned it from him,”[70] Zeus is portrayed as the perfect and original driver of the most perfect chariot, drawn by four horses representing the four elements. The hymn ends at the moment that the Divine Fire, having absorbed all the substance of the universe, prepared for a new creation.

The name 'Stoicism' derives from the Stoa Poikile (“Painted Porch”), a colonnade decorated with mythic and historical battle scenes, on the north side of the Agora in Athens, where Zeno and his followers gathered to discuss their ideas.

Zeno of Citium (c. 334 – c. 262 BC), founder of Stoicism

While Greek philosophies and Greek sciences became universal throughout the Middle East, many teachers were not themselves Greek, and much of the philosophy and science was not Greek in origin or inspiration. Greek philosophy at this time was divided into fairly definite schools, of which the most important were the Cynics, Sceptics, Epicureans and the Stoics. Of these, the most influential was that of the Stoics, which takes its name from the place where its founder Zeno (c. 334 – c. 262 BC) would lecture, the Stoa Poikile, “Painted Porch,” a colonnade decorated with mythic and historical battle scenes, on the north side of the Agora in Athens. Zeno from Citium, principal Phoenician city in Cyprus, and the son of a Phoenician merchant.

A.H. Armstrong commented that, “The Stoics accepted with enthusiasm the horrible Eastern superstition of astrology, along with all forms of divination, as perfectly corresponding to their view of the cosmos.”[71] The Stoics, who encouraged all forms of divination, were promoters of astrology. All events were thought to be causally related to one another, and therefore anything that happens must in theory be a sign of some future effect. All coming events are theoretically predictable, and astrology and divination were appealed to as evidence for the validity of the causal continuum. Unless signs of what will happen are available in natural phenomena, the Stoic aim to live in accordance with natural law would be considered to have no bearing. The Stoics argued that the gods could not be interested in human welfare unless they gave signs of future events, which can be interpreted by humans. If the forecasts of diviners and astrologers turn out to be false, the fault lies with the forecasters and not with the dreams, meteorological phenomena, flights of birds, entrails, and other evidence from which the future can be foretold.[72]

The heretical Magi, according to Bidez and Cumont, based on an apocryphal work titled the Apocalypse of Hystaspes, taught that the life of the world was divided into seven millennia, each under a planet and bearing the name of an associated metal. For six millennia, the God of good and the Spirit of Evil fought over the earth, until the Evil Spirit established his dominion and spread calamities everywhere. Zeus, or Ahura Mazda, decided to send Apollo, named Mithras, to kill the wicked with a torrent of fire, resurrect the dead, and establish a reign of justice and felicity. The seventh millennium, that of the Sun, would assure a prosperous Age of Gold, at the end of which the Sun-Power ended, and all the domination of the planets. The eighth millennium brought about a general conflagration, in which Fire took in and resolved the other three elements, when earth was renovated and all corruptibility eradicated.[73]

The Stoics believed that the divine “fire,” or God, generated the universe, and at the end of the Great Year, took it back into itself through a great conflagration. Eventually, the Fire would die down to Air, and finally to a Watery condition in which the seed for the next cycle would be. This cycle repeats itself eternally. The idea of recurring conflagrations was attributed by Nigidius Figulus, prominent Roman philosopher and astrologer of the first century BC, to the Magi,[74] and the notion that the world would be destroyed by fire is found in the Bundahishn.[75] It may have been from the Magussaeans that Heraclitus learned the same doctrine. Also, in the Republic, Plato made use of the Babylonian Sar, where it appears as the numerical equivalent of the period between global catastrophes outlined in the Timaeus, when the stars and seven planets are aligned with each other exactly as they were at the Creation. This, believes Nicholas Campion, “is the clearest evidence of his connections with Babylonian historical cosmology.”[76]

As Anthony Long has indicated, the Stoics were probably influenced by the doctrine of Berossus, who, interpreting the “prophecies of Bel,” attributed these disasters to the movement of the planets, and claimed to be able to determine the date of the Conflagration and the Great Flood.[77] Berossus maintained that the earth will burn whenever all the planets converge in Cancer, and are arranged in such a manner as to be aligned in a straight line, and that there will be a further Great Flood, when the planets converge in the same manner in Capricorn, since the change to summer occurs under the sign of Cancer, and the change to winter under Capricorn.[78]

Planetary Gods

According to Pliny, “the most surprising thing…is that there is absolutely no reference to magic in the Iliad, although so much of the Odyssey is taken up with magic that it forms a major theme, unless people put another interpretation on the story of Proteus, the songs of the Sirens, Circe and the summoning of the dead from Hades.”[79] Since the time of Homer, Greek literature was filled with the names of constellations, which for the most part, were translations or adaptations of the Babylonian names. However, of the relationship between Babylonia and ancient Greece, as Professor Cornford explains, “influences” were stressed instead of actual “borrowings” and that, “more than one attempt was made in the nineteenth century to show that the Greeks ‘borrowed’ the wisdom of the East; but when it was seen that the fascinating theory led its advocates beyond all bounds of historic possibility, the Orientalists were crushed in a sort of anti-Semite reaction, and they are only now beginning to lift their heads again.”[80] As Franz Cumont remarks:

…the reality of Hellenic borrowings from Semitic sources remains none the less indisputable. At a distant date Hellas received from the far East a duodecimal or sexagesimal system of measurement, both of time and of objects. The habit of reckoning in terms of twelve hours which we still use today, is due to the fact that the Ionians borrowed from the Orientals this method of dividing the day. Besides the acquaintance with early instruments, such as the Sun-dial, they owed to the observatories of Mesopotamia the fundamental data of their celestial topography: the ecliptic, the signs of the zodiac, the majority of the planets.[81]

Astrological thought in Greece was so prevalent, from the fifth century BC onward, that the general trend was to associate many of the Greek myths with the constellations. For every Babylonian god a Greek god who bore some resemblance to him in character was substituted as ruler of the same planet. The Greeks had once worshipped many gods, and it was not until the fourth century BC that they settled on twelve as the most important, as featured in the Frieze of the Parthenon, perhaps to accord with the number of signs in the Zodiac, a Greek word meaning “circle of life.” Although this cannot be proven, in the fourth century BC, the catalogue of astronomical information by Eudoxus of Cnidus, a pupil of Plato, though scientific in spirit, had adopted the vocabulary of myth, drawing on Babylonian data. Eudoxus, enumerating the twelve gods, assigned each one to a sign of the Zodiac. These were: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Apollo, Artemis, Ares, Aphrodite, Hermes, Athena, Hephaestus, and Hestia, the same twelve represented in the frieze of the Parthenon, except that Hestia was replaced with Dionysus. A century later, Aratus’ poems on the stellar formations, encouraged the same tendency. Each of the constellations were given mythological significance, and the signs of the zodiac were connected with heroes of fable.

Orion was the son of Poseidon who died when he was bitten on the heel by a scorpion. His hunting companion, Artemis, pleaded with Zeus to place his image among the stars. The scorpion was given a constellation in the opposite side of the sky. Perseus, after slaying the gorgon Medusa, rescued his lover Andromeda, daughter of the beautiful Ethiopian queen of Phoenicia.

The first sign of the Zodiac is Aries, the flying ram with the golden fleece. It is ruled by Mars, the god of war. Taurus, was the form of the bull Zeus assumed to seduce Europa, or the bull killed by Hercules. While a number of labors were attributed to Hercules in prior centuries and in the Iliad, the number of twelve, to accord with the Zodiac, was not resolved until the fifth century BC. The constellation of Hercules, who steps on the head of the serpent, Draco, was known as Bel, who killed the Dragon Tiamat, and also Gilgamesh, whose myths gradually changed into the twelve labors of Hercules.

Taurus is ruled by Venus, or Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Gemini, has two leading stars that are named in honor of twin boys most famous for accompanying Jason in the Argo during his quest for the Golden Fleece. Cancer was a gigantic sea crab that attacked Hercules, and Leo is the Nemean Lion he killed. Virgo, the virgin, was known as Astraea, the daughter of Zeus and Themis, before she became a constellation. Sagittarius, the archer is a half-man, half-horse, called a Centaur. A Centaur named Pholus helped Hercules hunt the Erymanthian boar. Capricorn is associated with Pan. He and some other gods were feasting along the Nile, when Typhon attacked them. The gods turned themselves into animals and fled, but Pan panicked and leapt feet first into the river, and that half of his body became a fish, while the other half became a goat. The myth of Aquarius is related to Ganymede, who was so beautiful that Zeus abducted him into heaven, where he gained immortality and served as his cup-bearer.

Greeks of the Classical age venerated Orpheus as the greatest of all poets and musicians; it was said that while Hermes had invented the lyre, Orpheus had perfected it. The herald’s staff of Hermes is an Asherah pillar, or the bronze serpents of Moses, poles with images of serpents which he had commanded the Israelites to erect to heal them from snake bites. The staff of Hermes, also known as the Caduceus, now the modern symbol of medicine, was an image of two intertwined snakes, and a pair of wings attached to the staff above the snakes. The Caduceus is related to the staff of the healer Asclepius, the Latin name of Hermes, who was the Greco-Roman god of medicine, son of Apollo. The Centaur Chiron taught him the art of healing, but Zeus, afraid he might render men immortal, slew him with a thunderbolt. Though Homer mentions him in the Iliad only as a skillful physician, he was eventually honored as a hero and worshipped as a god.

However, the man scholars believe to have been most likely responsible for bringing astrology to Greece was Berossus, a priest of Bel-Marduk who established himself at the school of astrology on the island of Cos about 280 BC. His lost Babyloniaca, dedicated to the Seleucid ruler Antiochus I, survives only in fragments, quotes by later Greek writers, who were later cited by Eusebius and Josephus. In his first book he describes the land of Babylonia, to which the half-man/half-fish Oannes and other divinities came out of the sea to teach men the rudiments of civilization. The second and third books contained the chronology and history of Babylonia and Assyria, beginning with the “ten kings before the Flood,” then the story of the Flood itself, and finally the story of the Assyrians, the last Babylonian kingdom, and the Persians. Using the Babylonian units of time, he maintained that between the first descent of kings and the Flood was a period of 120 Sar or 432,000 years, from Creation to the final conflagration will be 600 Sar, or one Sar times one Ner or 2,160,000 years, and from Alexander to the final conflagration, 12,000 years.[82]

In the fifth century BC, the doctors from the Greek Island of Cos attained a high reputation, calling themselves Asklepiadai, descendants of Asclepius. The founder of the Asklepiada was Hippocrates, born in 460 BC, known as the father of medicine. Little is known of Hippocrates’ life, and there may have been several men of his name, or he may have been the author of only some, or none of the books that comprise the Corpus Hippocraticum. The Asclepiadai may have been introduced to Chaldean doctrines by Berossus, who had taught the myth of Oannes, who, like Thoth and Hermes, was attributed the role of having taught the arts of civilization to humanity.

[1] F. M. Cornford. From Religion to Philosophy: A Study in the Origins of Western Speculation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), p. 126.

[2] West. The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), p. 59.

[3] Walter Burkert. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 4

[4] Diodorus Siculus. XL: 3.2

[5] “Forging an Identity,” The Oxford History of the Biblical World, p. 128.

[6] Dobin. Kabbalistic Astrology, p. 109.

[7] Histories, VI: 54

[8] Cited in Martin Bernal. Black Athena, Volume I: The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785 - 1985 (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1987), p. 110

[9] Cited in Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln. Holy Blood, Holy Grail, p. 277

[10] Cited in Eusebius. Preparation for the Gospel, VI: X, p. 279a.

[11] Bernal. Black Athena, p. 99

[12] Mary Boyce. A History of Zoroastrianism: Volume II: Under the Achaemenians (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1982), p. 232.

[13] M. L. West. The Orphic Poems (Clarendon Press, 1983), p. 178.

[14] Pliny. Natural History, p. 269

[15] 7.330, fr. 18, cited in W. K. C. Guthrie. Orpheus and Greek Religion (Princeton: The University of Princeton Press, 1993), p. 61.

[16] Plato. The Republic, 364b -365a.

[17] Orphica, cited in James H. Charlesworth,, ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Apocalyptic Literature & Testaments, Vol. I & II (New York: Doubleday, 1983), p. 799).

[18] Eusebius. Praeparatio Evangelica, 9.27 .1-37

[19] Bertrand Russell. A History of Western Philosophy. (London: Unwin Paperbacks, 1984), p. 37

[20] Clement of Alexandria. Exhortation to the Greeks, 2.12

[21] Clement. Protreptic, 34.5, quoted fr. Patricia Curd, ed. & Richard D. McKirahan Jr., trans. A Presocratics Reader: Selected Fragments and Testimonia (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company Inc., 1995), p. 39.

[22] Idid.

[23] trans. Franklin Phillip (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1999), p. 23.

[24] Joseph Campbell. Masks of God: Creative Mythology, Vol. 4 (London: Arkana, 1995), p. 267.

[25] Eusebius. Preparation for the Gospel. II: I, p. 48c.

[26] Herodotus. Histories, II. 171.

[27] Charles Penglase. Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod (New York: Routledge Press, 1994), p. 127

[28] Walter Burkert. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, trans. Pinder, Margaret E. & Burkert, Walter (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 5.

[29] Burkert. The Orientalizing Revolution, p. 94.

[30] Arnaldo Momigliano. Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), p. 126.

[31] Simplicius. Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, 164.24-25, 156.13-157.4, Cited in A Presocratics Reader, p. 57.

[32] Aristotle. Metaphysics 1.5 987a13, A Presocratics Reader, p. 21

[33] Menippus 6, cited in Kingsley. Ancient Philosophy, Mystery and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), p. 226. n. 33.

[34] Kingsley. Ancient Philosophy, Mystery and Magic, p. 227.

[35] Pliny. Natural History, XXX: 8

[36] Franz Cumont. Astrology and Religion Among the Greeks and Romans (Montana: Kessinger Publishing Company, 1912), p. 47.

[37] Histories, III:139.

[38] Library of History, 1.96.

[39] Porphyry. The Life of Pythagoras, 1.

[40] Ibid., 12.

[41] Ibid., 3.

[42] Josephus. Against Apion, p. 614.

[43] F. M. Cornford. From Religion to Philosophy: A Study in the Origins of Western Speculation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), p.176.

[44] Russell. A History of Western Philosophy, p. 49.

[45] Momigliano. Alien Wisdom, p. 142.

[46] I: 121 cited in Boyce. Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism, p. 107.

[47] Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers, III: 6-7

[48] Momigliano. Alien Wisdom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), p.143.

[49] Natural History, XXX: 3

[50] Eusebius. 13.12.1f..

[51] Eusebius. Preparation for the Gospel, IX: VI, p. 411a.

[52] Peter Kingsley. “Meetings with the Magi: Iranian Themes Among the Greeks, From Xanthus of Lydia to Plato’s Academy.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 5, p. 204.

[53] Proclus. In Rem Publicam Platonis, cited from Bidez & Cumont. Les Mages Hellenisees, t. II, p. 159.

[54] Stromata, Book V, Chap 14.

[55] Timaeus, vi, 136.

[56] Plato. Phaedrus, 265a.

[57] Plato. Symposium, 203a.

[58] Plato. Phaedrus, 244a.

[59] Plato. Phaedrus, 244b.

[60] Plato. Phaedrus, 265b–c.

[61] Plato. Symposium, 242c.

[62] Plato. Symposium, 211b–d; cited in Yulia Ustinova. Divine Mania Alteration of Consciousness in Ancient Greece (Routledge, 2018), p. 297.

[63] Yulia Ustinova. Divine Mania Alteration of Consciousness in Ancient Greece (Routledge, 2018), p. 296.

[64] The Republic, 423e–424a.

[65] Ibid., Book VII.

[66] Gorgias.

[67] “Notes and Queries (Precession of the Equinoxes Discovered by the Babylonians-‘Neptune’)” Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 21 (1927), p. 215; Fotheringham, J. K. “The indebtedness of Greek to Chaldean astronomy.” The Observatory, Vol. 51 (1928), p. 301-315.

[68] Plato. Timaeus, 22c.

[69] Plato. Phaedrus, 252c.

[70] Bidez and Cumont. Les Mages Hellenisees, p. 91.

[71] A.H. Armstrong. An Introduction to Ancient Philosophy (London: Methuen & Co. 1957), p. 125.

[72] Anthony A. Long. Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974), p. 212.

[73] Bidez & Cumont. Les Mages Hellenisees, p. 218.

[74] Ibid., II, p. 361, note 2.

[75] Bundahishn, Chap. XXX.

[76] Nicholas Campion. The Great Year: Astrology, Millenarianism and History in the Western Tradition (London: Arkana, Penguin Books), p. 243.

[77] Anthony Long. “The Stoics on World-Conflagration and Everlasting Recurrence”. The Southern Journal of Philosophy (1985) Vol. XXIII, Supplement, p. 18.

[78] Seneca. Naturales Quaestiones, 3.29.1.

[79] Pliny. Natural History, XXX:5-6.

[80] Cornford. From Religion to Philosophy, p. 2.

[81] Cumont. Astrology and Religion Among the Greeks and Romans, p. 42.

[82] Campion. The Great Year (London: Arkana, Penguin Books), p. 98.

Volume One

Introduction

Babylon

Ancient Greece

The Hellenistic Age

The Book of Revelation

Gog and Magog

Eastern Mystics

Septimania

Princes' Crusade

The Reconquista

Ashkenazi Hasidim

The Holy Grail

Camelot

Perceval

The Champagne Fairs

Baphomet

The Order of Santiago

War of the Roses

The Age of Discovery

Renaissance & Reformation

Kings of Jerusalem

The Mason Word

The Order of the Dragon