18. The American Civil War

Dixieland

The Curse of Ham, the controversial rabbinical interpretation of the Bible, became the basis for the subjugation of African slaves, ultimately creating an ideological divide that resulted in the American Civil War of 1861 to 1865, and persists to this day, serving as the basis for the Southern Strategy. The Curse of Ham also received the support of Freemasonry where it served to justify the exclusion of blacks. The first justification was articulated in Anderson’s Constitutions of 1923, where he outlined the legends of Freemasonry as well as its regulations or charges, including the “ancient landmarks.” Among these landmarks was the requirement that a candidate for Freemasonry “must be good and true Men, free-born, and of mature and discreet Age, no Bondmen no Women, no immoral or scandalous Men, but of good report.” According to the Constitutions:

No doubt Adam taught his Sons Geometry, and the use of it, in the several Art and Crafts convenient, at least for those early Times; for Cain, we find, built a city, which he called consecrated, or dedicated, after the name of his eldest son Enoch; and becoming the Prince of the one Half of Mankind, his posterity would imitate his royal Example in approving both the noble Science and the useful Art.... Noah, and his three sons, Japheth, Shem and Ham, all Masons true, brought with them over the Flood the Traditions and Arts of the Ante-deluvians, and amply communicated them to their growing Offspring.

However, as noted by Michael W. Homer, Lawrence Dermott—the first Grand Secretary of the rival Grand Lodge of Antients, organized in London in 1751, and who took a design by Rabbi Leon Templo as the basis for its coat of arms—published Ahiman Rezo, a history which provided one of the foundations upon which some American Masons could rationalize that Ham’s descendants, who they believed were black, were ineligible to join their lodges. According to Dermott:

It is certain that Freemasonry has existed from the creation, though probably not under that name; that it was a divine gift from God; that Cain and the builders of his city were strangers to the secret mystery of Masonry, that there were but four Masons in the world when the deluge happened; that one of the four, even the second son of Noah, was not a master of the art.

“In antebellum America,” according to David Goldenberg, the Curse of Ham “was the single greatest justification for maintaining black slavery, and for keeping that social order in place for centuries.”[1] Pre-Civil War Americans regarded Southerners as a distinct people, who possessed their own values and ways of life. During the three decades leading up to the Civil War, popular writers created a stereotype, now known as the “plantation legend,” that described the South as a land of aristocratic planters, southern belles and devoted household slaves.[2] This image of the South as “a land of cotton where old times are not forgotten” was popularized in 1859 in a song called “Dixie,” written by a Northerner named Dan D. Emmett, probably the best-known song to have come out of blackface minstrelsy. Emmett adopted the tune for a pseudo-African American spiritual in the 1870s or 1880s. Blackface performers added their own verses or altered the song. The chorus changed to: “I wish I was in Canaan.”[3]

Lionel Nathan de Rothschild (1808 – 1879) introduced in the House of Commons (1858)

Guiseppe Mazzini (1805 – 1872)

In the United States, Giuseppe Mazzini spearheaded a plan in league with the Rothschilds, to foment the Civil War, along the divide of the volatile issue of race. Central to this plan, reports Hagger, was the Rothschild family.[4] The Mazzini-Rothschild conspiracy devolved from Southern Jewish community networked with secret societies of the Skull and Bones, the Knights of the Golden Circle, and the Ku Klux Klan—who were inspired by the vigilantism of the Holy Vehm—who advanced that cause of slave-ownership against the abolitionists of the North. The Supreme Council, Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction—commonly known as the Mother Supreme Council of the World—founded in Charleston in 1801, was headed by Albert Pike, who headed the super-rite of Freemasonry known as the Palladian Rite with Mazzini.

Despite having been defeated in the War of 1812, and having signed the non-aggression treaty of 1814, Britain still longed to return America to its rule. As explained Nicholas Hagger:

Through the Scottish Rite lodges of the English obedience in the North, it controlled North-eastern wealth, but could not control the South, as Southern wealth was measured in slaves. If Britain was to have economic control over the South, slavery would have to be abolished. And so a plan was devised to divide America over the slavery issue—in the hope that America could be controlled economically and financially, if not militarily.[5]

The Rothschilds’ funding of the North was conducted through August Belmont (1813 – 1890). James Rothschild controlled the South via the Rothschild agent Judah P. Benjamin (1811 – 1884), a Southern lawyer and politician who came to be known as “the Jewish Confederate.”[6] Benjamin was the most prominent Jewish plantation owner, having built Belle Chasse Plantation in Plaquemines Parish, and owning 140 slaves.[7] As observed by Feuerlicht:

[W]hether so many [Southern] Jews would have achieved so high a level of social, political, economic and intellectual status and recognition, without the presence of the lowly and degraded slave, is indeed dubious. How ironic that the distinctions bestowed upon [Jewish] men like Judah P. Benjamin were in some measure dependent upon the sufferings of the Negro slaves they bought and sold with such equanimity.[8]

As indicated by Feuerlicht, despite all the abolitionist activities of Jews in the North, slavery had been implanted and nourished by Northern merchants, both Christian and Jewish.[9] During the eighteenth century, Jews actively traded in slaves, with some running the slave markets.[10] “Therefore,” as noted George Cohen, “it is hardly surprising that they became staunch upholders of the slavery system, in their unwillingness to relinquish these personal benefits.”[11] The most dominant Jewish slave traders on the American continent included Isaac Da Costa of Charleston, South Carolina in the 1750s, David Franks of Philadelphia in the 1760s, and Aaron Lopez of Newport in the late 1760s and early 1770s. Jacob Rader Marcus, a historian and Reform rabbi, wrote in his four-volume history of American Jews that over 75 percent of Jewish families in Charleston, South Carolina; Richmond, Virginia; and Savannah, Georgia, owned slaves, and nearly 40 percent of Jewish households across the country did.[12]

As revealed in the Financial Times, Nathan Mayer Rothschild and James William Freshfield, founder of Freshfields, benefited financially from slavery, as records from the National Archives show, even though both have often been portrayed as opponents of slavery. On August 3, 1835, in the City of London, two years after the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act, Nathan Mayer Rothschild and his brother-in-law Moses Montefiore came to an agreement with the chancellor of the exchequer to issue one of the largest loans in history, to finance the slave compensation package required by the 1833 act. The two bankers agreed to loan the British government £15m, with the government adding an additional £5m later. The total sum represented 40% of the government’s yearly income at the time, equivalent to some £300bn today. It was the biggest bail-out of an industry as a percentage of annual government expenditure, dwarfing the rescue of the banking sector in 2008.[13]

The money was not paid back by the British taxpayers until 2015.[14] The funds were not intended as reparations to the freed slaves to redress the injustices they suffered. Instead, the money went exclusively to the owners of slaves, who were being compensated for the loss of what had, until then, been considered their property.[15] According to the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership at the University College London, Rothschild himself was a successful claimant under the scheme, as part of “Antigua 390 (Mathews or Constitution Hill)”, where he was a beneficiary as mortgage holder to a plantation in Antigua which had 158 slaves in his ownership, he received a £2,571 payment at the time (worth £246 thousand in 2020.[16]

August Belmont Sr. (1813 – 1890)

The Rothschilds wanted to start a central bank in America. The second America, created by James Madison in 1816, had collapsed in 1836. Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s son Lionel Rothschild (1808 – 1879) and his uncle James (1792 – 1868) were behind the funding of both North and South in the planned division. The North was to be annexed to Canada as a British colony under Lionel, who was based in London. In 1851, Mazzini began the process of bringing about a civil war by forming revolutionary groups throughout the United States to intensify the debate on slavery.[17] In 1857, a meeting in London convened by Mazzini’s Illuminati decided that there should be a conflict between North and South, and Lionel Rothschild used August Belmont as an emissary, together with Jay Cooke, the Seligman brothers and Speyer and Co.

Belmont, whose real name was August Schoenberg, was a German-born Jew who would become party chairman of the Democratic National Committee during the 1860s, and the founder of the Belmont Stakes, third leg of the Triple Crown series of American horse racing. Belmont began his first job as an apprentice to the Rothschild banking firm in Frankfurt. In 1837, he set sail for Havana where he was charged with the Rothschilds’ interests in the Spanish colony of Cuba. In the financial recession and Panic of 1837, like hundreds of American businesses, the Rothschilds’ American agent in New York City collapsed. As a result, Belmont stayed in New York and began a new firm, August Belmont & Company, and restored the Rothschilds’ wealth.[18]

Friends of the Blacks

"Mortals are equal, it is not birth, but virtue alone that makes the difference".

Illuminatus Jacques Pierre Brissot (1754 – 1793), founder of Amis de Noirs (“Friends of the Blacks”)

According to the Marquis de Luchet, in Essai sur les Illuminés, the Illuminati, who excelled in proclaiming ideals that looked noble while secretly aiming at subversion, were behind the creation of a secret society to support the cause of abolitionism, called Amis de Noirs (“Friends of the Blacks”), founded by Illuminatus Jacques-Pierre Brissot, a member of Bonneville’s Social Club. In England, Brissot had been invited by Thomas Clarkson (1760 –1846), to attend a meeting of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Clarkson had become convinced of the need to end the slave trade after writing a prize-winning essay, titled An essay on the slavery and commerce of the human species, particularly the African, translated from a Latin Dissertation (1786). Brissot founded his own abolitionist society in Paris in 1788, called Amis des Noirs (“Friends of the Blacks”).

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745 – 1799), the “Black Mozart”

Assisting Brissot in his cause was Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745 – 1799), a virtuoso musician and composer, a conductor of the leading symphony orchestra in Paris, and a renowned champion fencer. Born in the French colony of Guadeloupe, he was the son of George Bologne de Saint-Georges, a wealthy married planter, and Anne dite Nanon, his sixteen-year-old Senegalese slave. When he was young, Saint-Georges’ father took him to France, where he was educated. Saint-Georges' first opera, with a libretto by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, future author of Les Liaisons dangereuses and friend of the Marquis de Sade, was performed in 1777, at the Comédie-Italienne. During the French Revolution, the younger Saint-Georges served as a colonel of the Légion St.-Georges, the first all-black regiment in Europe, fighting on the side of the Republic. In 1769, he played violin in Gossec’s orchestra, Le Concert des Amateurs. When Gossec took a position at another orchestra in 1773, Saint-Georges took over as director, and under his leadership, Le Concert des Amateurs became one of the best in Europe.

By the mid-1780s, Illuminatus Philippe, Duke of Orléans, also known as Philippe Égalité, became Saint-Georges’s patron. It was with the duke that Saint-Georges became involved with the abolitionist movement in France and England. When Philippe sent Saint-Georges to England to secure the Prince of Wales’s support, his chief of staff, Brissot, privately asked Saint-Georges to meet with leading abolitionists in England to ask for their advice on how to advance the movement in France. Saint-Georges met with abolitionists William Wilberforce, John Wilkes, Clarkson. He spent the next two years between the two countries, continuing his work with the movement and having British abolitionist literature translated into French for the Société des amis des Noirs. During the French Revolution, Saint-Georges become colonel of his own regiment, the Légion Saint-Georges, the first all-black regiment in Europe. It attracted volunteers from all over the country, including Thomas Alexandre Dumas, the legendary father of Alexandre Dumas, author of the Count of Monte Christo. Dumas took over from Saint-Georges when he was arrested and very nearly executed during the Terror. By the time he passed away in 1799, Saint-Georges was a legend. US President John Adams referred to him “the most accomplished man in Europe.”[19]

Design of the medallion created as part of anti-slavery campaign by Josiah Wedgwood (1730 – 1795), a member of the Lunar Society

Brissot used the same seal as that chosen by the British society, a medallion representing a kneeling Black man with the motto “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?” translated into French as “Ne suis-je pas ton frère?” The medallion was designed by Josiah Wedgwood (1730 – 1795), who was active in the Lunar Society, where he became friends with Joseph Priestley and its founders Matthew Boulton and Erasmus Darwin, Freemason and father of Charles Darwin.[20] Wedgwood was also a strong supporter John Wilkes, a member of the Hellfire Club and a distant relative of Abraham Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth.[21] In 1788, Wedgwood sent copies of his medallions to Benjamin Franklin, then president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, who was convinced of its value in bringing attention to the cause.[22]

The Amis des Noirs created a Regulating Committee, composed of Illuminati like Condorcet, Mirabeau, Sieyès, the Duc de la Rochefoucauld and La Fayette, which was also in intimate correspondence with the Central Committee of the Grand Orient of France.[23] The Amis des Noirs opposed slavery, which was institutionalized in the French colonies of the Caribbean and North America, and the African slave trade. During the five years of its operation, it published anti-slavery literature and frequently addressed its concerns on a substantive political level in the National Assembly, which passed the Universal Emancipation decree, which effectively freed all colonial slaves and gave them equal rights. This decision was later reversed under Napoleon, who tried unsuccessfully to reinstitute slavery in the colonies and to regain control of Saint-Domingue, where a slave rebellion was underway.

In the United States, where he had visited Philadelphia’s constitutional convention following the American Revolution, Brisssot had become inspired by Thomas Jefferson’s humanitarian ideals as expressed in the Declaration of Independence. The first attempts to end slavery in the British/American colonies came from Thomas Jefferson and some of his contemporaries. Despite the fact that Jefferson was a lifelong slaveholder, he included strong anti-slavery language in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence, but other delegates took it out. Benjamin Franklin, also a slaveholder for much of his life, became a leading member of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, the first recognized organization for abolitionists in the United States.[24] Following the American Revolution, Northern states abolished slavery, beginning with the 1777 Constitution of Vermont, followed by Pennsylvania's gradual emancipation act in 1780. Other states with more of an economic interest in slaves, such as New York and New Jersey, also passed gradual emancipation laws, and by 1804, all the Northern states had abolished it, although this did not mean that existing slaves were freed. In 1801, as President, Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves and it took effect in 1808, which was the earliest allowed under the Constitution. In 1820 he privately supported the Missouri Compromise, believing it would help to end slavery. In his 1821 autobiography, he wrote “nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate, then these people are to be free; nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government. Nature, habit, opinion has drawn indelible lines of distinction between them.”[25]

Anti-Slavery Society

Thomas Clarkson (1760 – 1846) leading the Anti-Slavery Convention at Freemasons’ Hall in London (1840).

William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833)

Chiefly responsible for advancing the cause for the abolition of slavery were Evangelical Christians, who were affiliated with the crypto-Sabbatean Count Zinzendorf’s Moravian Church, who exploded in the United States with the First and Second Great Awakenings. Zinzendorf was critical of slavery and supported the first Moravian missionaries to the American colonies. Before the American Revolution, Baptist and Methodist evangelicals in the South had promoted the view of the common man’s equality before God, and welcomed slaves as Baptists and accepted them as preachers.[26] Baptists became the largest Christian community in many southern states, including among the black population.[27] It was only when John Wesley, who had been in contact with Zinzendorf, became actively opposed to slavery that the small protest became a mass movement resulting in the abolition of slavery. Wesley influenced George Whitefield—a friend of Benjamin Franklin also influenced by Zinzendorf—to journey to the colonies, spurring the transatlantic debate on slavery.[28] Whitefield nevertheless owned several hundred slaves himself.[29] Several of the leaders of the Great Awakening who endorsed this perspective of slavery including Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards, attempted to teach the slaves to accept their inferior status as accepting the will of God.[30] Edwards as well owned several slaves throughout his lifetime, and a “Negro boy named Titus” was listed among the “Quick Stock” in the inventory of his will.[31]

In 1791, Wesley wrote to his friend, the English politician William Wilberforce, to encourage him in his efforts to end the slave trade. Wilberforce had become an evangelical Christian in 1785, and became a leader of the Clapham, a group of influential Christian like-minded Church of England social reformers based in Clapham, London, at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Members of the Clapham sect were chiefly prominent and wealthy evangelical Anglicans. They shared in common political views concerning the liberation of slaves, the abolition of the slave trade and the reform of the penal system. The Clapham sect have been credited with playing a significant part in the development of Victorian morality. In the words of historian Stephen Tomkins, “The ethos of Clapham became the spirit of the age.”[32] The sect are described by Tomkins as:

A network of friends and families in England, with William Wilberforce as its center of gravity, who were powerfully bound together by their shared moral and spiritual values, by their religious mission and social activism, by their love for each other, and by marriage.[33]

Thomas Clarkson (1760 – 1846)

In 1783, when Wilberforce and his companions travelled to France—where their presence aroused police suspicion that they were English spies—and visited Paris, meeting prominent Freemasons like Benjamin Franklin, General Lafayette as well as Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI.[34] Madame Germaine de Staël’s was impressed by the speeches Wilberforce delivered at a meeting held at Freemasons’ Hall in London, in 1814. She met Wilberforce by special request at a dinner party hosted by the Duke of Gloucester (1776 – 1834), nephew and son-in-law of King George III. She described Wilberforce as the “wittiest man in England.”[35] Wilberforce later recalled their evenings by saying, “The whole scene was so intoxicating, even to me. The fever arising from it is not yet gone.”[36] Madame de Staël became converted to Wilberforce’s cause, and lent considerable support to Abolition when she returned to Paris.[37]

Wilberforce headed the parliamentary campaign against the British slave trade for twenty years until the passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807. In 1787, Wilberforce had come into contact with Thomas Clarkson, who called upon him to champion the cause to parliament. As the British abolitionists had been somewhat disappointed with their own campaign in Britain, Wilberforce, hoping that the ideals of the French Revolution would support the cause, entrusted Clarkson with the mission to France to gain the collaboration of the French abolitionists. Upon his arrival in Paris, in August 1789, Clarkson thus immediately contacted the French opponents to the slave trade, Condorcet, Brissot, Clavière, La Fayette and Illuminatus Comte de Mirabeau, with whom he was particularly impressed. However, certain members of the Assemblée Nationale accused Clarkson of being a spy for the British in an attempt to cause France to lose its colonies, and suspected Mirabeau of complicity. Clarkson was even physically threatened and required the assistance of the Garde nationale, commanded over by General Lafayette to protect him.[38] With the subsequent crackdown on the moderate Girondins in 1793, Brissot was beheaded in 1793.

Wilberforce made his last public appearance when he was named by Clarkson to server as the chairman of the Anti-Slavery Society convention of 1830, at Freemasons’ Hall in London, the headquarters of the United Grand Lodge of England and the Supreme Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons of England, as well as being a meeting place for many Masonic Lodges in the London area.[39] In 1833, the British government passed the Slavery Abolition Act, advocated by Wilberforce, which abolished slavery in the British Empire the following year.

Frederick Douglass (1818 – 1895)

Clarkson was the principal speaker in 1840 at the opening of the first World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in Freemasons’ Hall, London. In 1846, the World Evangelical Alliance was founded there as well. In 1846 Clarkson was host to Frederick Douglass (1818 – 1895), a prominent African-American abolitionist, on his first visit to England. Douglass was of mixed race, which likely included Native American and African on his mother’s side, as well as European, though his father was “almost certainly white,” as shown by historian David W. Blight.[40] In 1843, Douglass joined other speakers in the American Anti-Slavery Society’s “Hundred Conventions” project, a six-month tour at meeting halls throughout the eastern and midwestern United States. Douglass wrote several autobiographies, notably describing his experiences as a slave in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), which became a bestseller, and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). At risk after passage in the US of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Douglass became legally free in England when British friends raised the money and purchased his freedom from his American owner.

In the two decades after the Revolution, during the Second Great Awakening, Baptist preachers abandoned their pleas that slaves be freed, causing a split between the Northern and Southern branches of the denomination.[41] The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) was organized in 1845 at Augusta, Georgia, by Baptists in the Southern United States who split with northern Baptists over the issue of slavery, specifically whether Southern slave owners could serve as missionaries. The oldest Baptist church in the South, First Baptist Church of Charleston, South Carolina, was organized in 1682. With more than 15 million members as of 2015, SBC is the world’s largest Baptist denomination, the largest Protestant denomination in the United States, and the second-largest Christian denomination in the United States after the Catholic Church.

Abolitionists were categorized as hypocrites who wanted the South to free her slaves, but would not give the freed slaves jobs if they journeyed North. At the time of the split, the Southern Baptists used the Curse of Ham as a justification for slavery claiming they were serving God’s will.[42] Clergy even suggested Blacks were better off as slaves. Christianity, they claimed, not only served to civilize the Africans, but as The Baptist Messenger reported in 1850: “The arm of force has been rendered unnecessary by the peaceful influence of the gospel. The planters testify that this religious reformation has increased the value of their property 10 or 12 per cent.”[43]

States’ Rights

John C. Calhoun (1782 – 1850), a leading proponent of states’ rights

However, by the 1850s, southerners were losing their hold on national power, contributing to a backlash against the North that rallied to save their so-called Southern way of life. For fifty of the first 62 years of US history, Southerners such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe and Andrew Jackson, dominated the executive branch of the American government. The title of “Democrat” has its beginnings in the South, going back to the founding of the Democratic-Republican Party in 1793 by Jefferson and Madison. After being the dominant party in American politics from 1800 to 1829, the Democratic-Republicans split into two factions by 1828: the federalist National Republicans, and the Democrats. Northern Democrats were opposed to the Southern Democrats on the issue of slavery. Northern Democrats. The Southern Democrats (known as “Conservative Democrats”), reflecting the views of the late John C. Calhoun, insisted slavery was national.

Calhoun was the South’s recognized intellectual and political leader from the 1820s until his death in 1850. He had an illustrious political career, serving as a congressman for his home state of South Carolina, Vice President under both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, and a U.S. senator. Calhoun is remembered for strongly defending slavery and for advancing the concept of minority rights in politics in the interests of the white South. In the late 1820s, his views changed radically and he became a leading proponent of states’ rights, limited government.

Calhoun was certain that the issue of slavery was doomed to divide the country, and likely result in war. In a famous speech on the Senate floor on February 6, 1837, Calhoun asserted that slavery was a “positive good,” and that in every wealthy and civilized society one portion of the community has always lived on the labor of an other. According to Calhoun:

Be it good or bad, [slavery] has grown up with our society and institutions, and is so interwoven with them that to destroy it would be to destroy us as a people. But let me not be understood as admitting, even by implication, that the existing relations between the two races in the slaveholding States is an evil:–far otherwise; I hold it to be a good, as it has thus far proved itself to be to both, and will continue to prove so if not disturbed by the fell spirit of abolition. I appeal to facts. Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually.[44]

Calhoun believed that politicians in the North pandered to the anti-slavery vote, and that politicians in the slave states sacrificed Southern rights in an effort to placate the Northern wings of their parties. Thus, the essential first step in any successful assertion of Southern rights had to be the abandonment of all party affiliations. In 1848–49, Calhoun called for Southern unity, and was the driving force behind the drafting and publication of the “Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents.”[45] It alleged Northern violations of the constitutional rights of the South, and warned Southern voters to expect forced emancipation of slaves in the near future, followed by their complete subjugation by an unholy alliance of unprincipled Northerners and blacks. Whites would flee and the South would “become the permanent abode of disorder, anarchy, poverty, misery, and wretchedness.”[46] Only the immediate unity of Southern whites could prevent such a disaster.[47]

According to Calhoun’s biographer Margaret L. Coit, “The startling fact is that every principle of secession or states’ rights which Calhoun ever voiced can be traced right back to the thinking of intellectual New England in the early eighteen-hundreds.”[48] In 1802, Calhoun went to Yale College in Connecticut, which was dominated by its President, Timothy Dwight, an important figure in the Second Great Awakening, who became his mentor. Dwight also expounded on the strategy of secession from the Union as a legitimate solution for New England’s disagreements with the national government.[49] Calhoun studied law at the nation’s only real law school, Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, where he worked with Tapping Reeve and James Gould. According to Coit, “…Dwight, Reeve, and Gould could not convince the young patriot from South Carolina as to the desirability of secession, but they left no doubts in his mind as to its legality.”[50]

When he was admitted to Yale in 1802, Calhoun was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, the first American Greek Letter college fraternity and most prestigious academic honor society in the United States.[51] Phi Beta Kappa was heavily influenced by Freemasonry. The group consisted of students who frequented the Raleigh Tavern as a common meeting area off the college campus, where Masons also reputedly met.[52] Thomas Smith, one of the fraternity’s founders, belonged to the Williamsburg lodge, which operated under a charter from the Grand Lodge of England. Nine of the other original members later did became Freemasons within the first year.[53]

Skull and Bones

Skull and Bones members from the class of 1861.

William Huntington Russell (1809 – 1885)

In 1826, Captain William Morgan disappeared in upstate New York, allegedly abducted and murdered for publishing and exposing Masonic ritual. The story of Morgan’s disappearance resulted in an anti-Masonic period, which lasted until about 1840, marked the beginning of an explosion in published ritual exposures. The crisis faced by Freemasons also effected Phi Beta Kappa, when in 1831 A Ritual of Freemasonry, Illustrated by Numerous Engravings; with Notes and Remarks was published, to which was added a Key to the Phi Beta Kappa by Avery Allyn, an anti-Masonic lecturer of the time. The backlash resulted in the fraternity abandoning its secrecy and becoming little more than an academic honor society.[54]

In protest, members from the Linonia, the Brothers in Unity and the Calliopean societies of Yale diverged from their respective groups and formed the Skull and Bones society. Calhoun had been a member of the Brothers in Unity, to which also belonged Alphonso Taft, who founded Skull and Bones with William Huntington Russell. Russell was a descendant of several old New England families, including those of Pierpont, Hooker, Willett, Bingham, and Russell. According to Alexandra Robbins, author of Secrets of the Tomb, while he was in Germany, Russell had befriended the leader of a German secret society, itself an outgrowth of the Illuminati, that employed the death’s head as its logo. When Russell returned to the United States, he joined with Taft to found what they called the Brotherhood of Death. They adopted the numerological symbol 322 because they were the second chapter of the German sister organization and were founded in 1832. According to Robbins, “They worshiped the goddess Eulogia, celebrated pirates, and plotted an underground conspiracy to dominate the world.” Among the “gifts of tribute to the goddess” purloined by the order were a card table on which Calhoun used to play. Eventually joining the order was James Gould’s grandson, James Gardner Gould, eldest son of Judge William Tracy Gould.[55]

As reported by Robbins, by the late 1800s, Yale was dominated by the three prestigious secret senior societies, Skull and Bones, Scroll and Key, and Wolf’s Head. Scroll and Key had joined Skull and Bones in 1842 and quickly became a powerful secret society on campus. Scroll and Key was established in 1841 by students who resented not having been “tapped” to join Skull and Bones. However, its reputation is that it is more serious and literary than Bones. Its alumni include descendants of Mayflower families, as well as former Yale President A. Bartlett Giamatti.[56] Since 1868, Mark Twain was an honorary member. Twain’s Letters from the Earth, were among the earliest to actually feature Satan as a heroic character. From then on, Satan and Satanism started to gain a new meaning outside of Christianity.[57]

Between 1872 and 1936, of the thirty-four consecutively elected alumni fellows of Yale, seventeen were Skull and Bones and seven were Scroll and Key. Between 1862 and 1910, Bonesmen were forty-three of the forty-eight university treasurers. Every university secretary from 1869 to 1921 was a Bonesman, as were 80 percent of professors between 1865 and 1916. Between 1886 and 1985, the university president was an alumnus of Skull and Bones, Scroll and Key, or Wolf’s Head for sixty-eight of the ninety-nine years. Wolf’s Head members would eventually include future senator Thurston Morton, ambassador Douglas MacArthur, Jr., and Yale president A. Whitney Griswold.[58]

Alphonso Taft (1810 – 1891) was an American jurist, diplomat, politician, Attorney General and Secretary of War under President Ulysses S. Grant. He was also the founder of an American political dynasty, and father of President and Chief Justice William Howard Taft.

Taft would become Attorney General and Secretary of War under President Ulysses S. Grant. Taft was the first in the Taft family political dynasty. His son, William Howard Taft, was the 27th President of the United States and the 10th Chief Justice of the United States, and was a member of Yale’s Skull and Bones like his founder father; another son, Charles Phelps Taft, supported the founding of Wolf's Head Society at Yale; both his grandson and great-grandson, Robert A. Taft I (also Skull and Bones) and Robert Taft Jr., were U.S. Senators; his great-great-grandson, Robert A. Taft II, was the Governor of Ohio from 1999 until 2007. William Howard Taft III was ambassador to Ireland; William Howard Taft IV worked in several Republican administrations, most recently that of George W. Bush.

In September 1836, Russell opened a private prep school for boys that would become known as the New Haven Collegiate and Commercial Institute, or more popularly as the Russell Military Academy, that “fitted” students to apply for entrance to nearby Yale or West Point. He foresaw a Civil War in the future, and wanted to make sure his boys were prepared to fight for the Union. His students were so well schooled in military affairs that on the outbreak of Civil War some were enlisted as drill instructors.[59] During the American Civil War, the school of 130 to 160 pupils furnished more than one hundred officers for the Union Army, as well as many drill masters and volunteers.

Many Skulls and Bones members supported the Southern cause for succession that led to the Civil War. Young South Carolinian Joseph Heatly Dulles, whose family bought their slaves with the money from contract-security work for the British conquerors in India, had been a member of the Brothers in Unity. At Yale, Dulles worked with the Northern secessionists and attached himself to Daniel Lord. The Lords became powerful Anglo-American Wall Street lawyers, and J.H. Dulles’s grandson was the father of John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, future head of the CIA.[60]

From 1885 to 1891, Bonesman William M. Evarts was a U.S. Senator from New York. During President Rutherford B. Hayes’s administration he was United States Secretary of State. He raised funds to build up the Masonic Statue of Liberty building in New York City. Henry Rootes Jackson was a leader of the 1861 Georgia Succession Convention and post-Civil War President of the Georgia Historical Society, and a major general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. John Perkins, Jr. was chairman of the 1861 Louisiana Succession Convention. William Taylor Sullivan Barry was a national leader of the secessionist wing of the Democratic Party during the 1850’s and chairman of the 1861 “Mississippi” Secession Convention. Morris R. Waite was the chief justice of the United States Supreme Court at 1847-88, whose rulings destroyed many rights of African Americans gained after the Civil War. Also, he helped his cohorts Taft and Evarts arrange the 1876 Presidential settlement scheme to pull the rights-enforcing U.S. troops out of the South.[61]

Manifest Destiny

American Progress (1872) by John Gast.

George Nicholas Sanders (1812 – 1873), member of the Carbonari and suspected Lincoln assassination conspirator

Southern presidents had also been largely responsible for the country’s great expansion. Thomas Jefferson brought about the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803 and James Knox Polk (1795 – 1849) was a supporter of the concept of Manifest Destiny. John O’Sullivan (1813 – 1895), editor of the Democratic Review, is generally credited with coining the term Manifest Destiny in 1845. The Democratic Review in New York City was the center of the Young America Movement, which was inspired by European reform movements such as the Young Hegelians, Junges Deutschland and Mazzini’s Young Italy. In their heyday in the 1840s and 1850s, argues Yonatan Eyal, Young America were led by Polk, Stephen Douglas, Franklin Pierce, and August Belmont.[62] Young America was founded in 1845 by Edward DeLeone, who was later a confidant of Freemason Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy. The other founder of Young America was George Nicholas Sanders (1812 – 1873). Both were members of the Carbonari, and Sanders was a close friend of Mazzini. In January 1860, Sanders admitted in conversation that he was a friend of Louis Blanqui, who had worked with Buonarroti, and a member of society at Paris called the “Club Blanqui.”[63]

Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1810 – 1850), close friend of Mazzini

The motto of the Democratic Review was “The best government is that which governs least.” Contributors included Samuel Tilden, William Cullen Bryant, George Bancroft, Herman Melville and two its members, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe. The Democratic Review also published some of the early work of Walt Whitman, James Russell Lowell, and Henry David Thoreau. American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804 – 1864) graduated from Bowdoin College in 1825, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.[64] Hawthorne married O’Sullivan’s goddaughter, Sophia Amelia Peabody. The couple were close friends of a fellow-contributor to the Democratic Review, Sarah Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1810 – 1850) an American journalist and women’s rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movement. Fuller was also influenced by the work of Swedenborg.[65] Thomas Carlyle and his wife, Jane, had introduced her to Mazzini.[66] Fuller had met Mazzini in London where she began a friendship and correspondence with him, regarding him as “not only one of the heroic, the courageous, and the faithful,” she wrote, “but also one of the wise.”[67] Margaret Fuller actually fought in the Italian revolution alongside her lover, Giovanni Ossoli, who was a friend of Mazzini.[68] Fuller was also an inspiration to poet Walt Whitman.

O’Sullivan wrote that Manifest Destiny was the “divine destiny” of America “to establish on earth the moral dignity and salvation of man.”[69] O’Sullivan described the general purpose of the Young America in an 1837 editorial for the Democratic Review:

All history is to be re-written; political science and the whole scope of all moral truth have to be considered and illustrated in the light of the democratic principle. All old subjects of thought and all new questions arising, connected more or less directly with human existence, have to be taken up again and re-examined.[70]

Manifest Destiny had been seen as necessary to enforce the Monroe Doctrine, formulated by future President John Qincey Adams (1767 – 1848) formulated in 1823, which warned Europe that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open for European colonization. Historian William E. Weeks has noted three key themes that lent support to the notion of Manifest Destiny: the virtue of the American people, their mission to spread their institutions and the destiny under God to remake the world in the image of the United States.[71] The origin of the first theme, later known as American exceptionalism, was often traced to America's Puritan heritage, particularly the Rosicrucian John Winthrop’s famous “City upon a Hill” sermon of 1630, in which he called for the establishment of a virtuous community that would be a shining example to the Old World.[72] Illuminatus Thomas Paine, in his influential 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, echoed the notion, arguing that the American Revolution provided an opportunity to create a new, better society.

President James Knox Polk (1795 – 1849)

In 1842, US President John Tyler (1790 –1862) applied the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii and warned Britain not to interfere there, which began the process of Hawaii’s annexation to the US. The phrase “manifest destiny” originated in the Oregon boundary dispute between the United States and Britain, when. Rejecting a proposal by US President John Tyler’s to divide the region along the 49th parallel, the British instead proposed a boundary along the Columbia River. Presidential candidate Polk exploited the popular outcry from Advocates of manifest destiny and the Democrats called for the annexation of “All Oregon” in the 1844 U.S. Presidential election. As president, however, Polk sought compromise to the dismay of the most ardent advocates of manifest destiny. When the British refused the offer, American expansionists responded with slogans such as “The whole of Oregon or none” and “Fifty-four forty or fight.” When Polk moved to terminate the joint occupation agreement, the British finally agreed in early 1846 to divide the region along the 49th parallel, leaving the lower Columbia basin as part of the United States. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 formally settled the dispute.

On December 2, 1845, Polk announced that the principle of the Monroe Doctrine should be strictly enforced, reinterpreting it to argue that no European nation should interfere with the American western expansion.[73] Manifest destiny played an important role in the expansion of Texas and American relationship with Mexico. Shortly after attaining the presidency in 1845, Polk, who was also a member of Young America, provoked a war with Mexico for the purpose of obtaining more slave states. During Polk’s presidency, the United States expanded significantly with the annexation of the Republic of Texas, the Oregon Territory, and the Mexican Cession following the American victory in the Mexican–American War. In the July–August 1845 issue of the Democratic Review, O’Sullivan published an essay entitled “Annexation,” which called on the US to admit the Republic of Texas into the Union. The Republic of Texas had declared independence from the Republic of Mexico in 1836. However, the leadership of both major American political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, opposed the admission of Texas, a vast slave-holding region.

Beginning in 1843, President John Tyler made the annexation of Texas his leading priority, and through secret negotiations with the Houston administration, he secured a treaty of annexation April 1844. And though both major American political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, opposed the admission of Texas, which was widely viewed as a pro-slavery initiative because it would add another slave state to the union.[74] Nonetheless, in April 1844, John C. Calhoun, as Secretary of State, reached a treaty with Texas providing for its annexation. Polk secured the Democratic nomination on a Manifest Destiny platform in favor of annexation and narrowly defeated anti-annexation Whig Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election. The Democratic-dominated House of Representatives passed an amended bill expanding on the pro-slavery provisions of Tyler’s treaty. When Polk took office, he encouraged Texas to accept Tyler’s annexation bill, accepting Texas as the 28th state of the Union. Texas formally joined the union on February 19, 1846.

Following the annexation of Texas, relations between the United States and Mexico deteriorated, resulting a few months later in the Mexican–American War, from 1846 to 1848. In 1845, Polk had made a proposition to purchase Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico from Mexico, and to agree upon the Rio Grande river as the southern border of the United States. When Mexico rejected that offer, Polk moved American troops commanded by Major General Zachary Taylor (1846 – 1848) south into the Nueces Strip. Taylor was a descendant of Elder William Brewster, the Pilgrim leader of the Plymouth Colony, a Mayflower immigrant, and a signer of the Mayflower Compact. Taylor’s father, Richard Taylor, had served as a lieutenant colonel in the American Revolution. In July 1845, Polk sent Taylor to Texas, and by October he commanded 3,500 Americans on the Nueces River, ready to take the disputed land by force.

In November 1845, Polk had secretly sent John Slidell (1793 – 1871) to Mexico City with an offer to the Mexican government for the disputed land and other Mexican territories. Slidell, who was the uncle of August Belmont’s wife, was a U.S. Senator from Louisiana and later Southern secessionist who served the Confederate States government as a foreign diplomat and potential minister to Great Britain and French Emperor Napoleon III. When the Mexican again rejected the offer, Slidell returned to the United States, and Polk ordered General Taylor to garrison the southern border of Texas in 1846 and then moved into Texas and marched as far south as the Rio Grande, where he began to build a fort near the river's mouth on the Gulf of Mexico. The Mexican government regarded this action as a violation of its sovereignty, and immediately prepared for war. Following a United States victory and the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War on February 2, 1848, when Mexico surrendered its claims to Texas and the Rio Grande border was accepted by both nations.

In recognition of his victory at Buena Vista, on July 4, 1847, Taylor was elected an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati, whose Virginia branch included his father as a charter member. Polk declined to seek re-election for the 1848 election, and the Democratic ticket was defeated by Taylor, a slaveholder, who had won the Whig presidential nomination with the strong backing of slave state delegates.[75] Taylor became the 12th president of the United States, serving until his death in July 1850.

The Free Soil Party first raised the warning of an active Slave Power or Slavocracy in 1848, arguing that the annexation of Texas as a slave state was a terrible mistake. Slave Power, a term popularized by antislavery writers such as Frederick Douglass, was the perceived political power in the American federal government held by slave owners during the 1840s and 1850s, prior to the Civil War. Politicians who emphasized the theme included John Quincy Adams, Henry Wilson and William Pitt Fessenden. Abraham Lincoln also used the concept after 1854. It was believed that a small group of rich slave owners had seized political control of their own states and were working to take over the White House, the Congress, and the Supreme Court in order to expand and protect slavery. The argument was later widely used by the Republican Party that formed in 1854–55 to oppose the expansion of slavery.[76]

Happening in the same year as the Mexican–American War was the Year of Revolutions of 1848, fomented by the agents of the revived Illuminati, the Philadelphes and the Carbonari. These upheavals were celebrated by Americans with frequent parades and proclamations, and foreign revolutionaries like Hungarian Mason Louis Kossuth (1802 – 1894) emerged as national celebrities. At the highest levels of government, the United States offered diplomatic support. In May of that year, John C. Calhoun used his connections with the Prussian minister-resident in America to encourage the formulation of “constitutional governments” upon the “true principles” embodied in the American federal system. According to Calhoun, the construction of such political institutions necessary for “the successful consummation of what the recent revolutions aimed at in Germany” and “the rest of Europe.” The White House also reflected this revolutionary enthusiasm.[77]

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April – 1861)

After 1848, a faction of Democrats, concerned about the nation’s failure to support “democratic” revolutions abroad, formed a group identified as Young America.[78] They intended to contrast themselves from the caution of their party’s so-called Old Fogies. Young America argued that the nation could only secure its ideals through more forceful “expansion and progress.” Stephen A. Douglas (1813 – 1861), the U.S. senator from Illinois who would run against Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election, became the leading political figure for citizens who wished to make America a more effective beacon of revolution overseas. Douglas, however, failed to win the Democratic Party nomination for the presidency in 1852.

Another Democrat, Franklin Pierce (1804 – 1869), was elected to the White House that year after making numerous appeals to Young America sentiment. Pierce joined the Athenian Society, a progressive literary society, alongside Hawthorne, with whom he formed lasting friendships.[79] Hawthorne wrote the glowing biography The Life of Franklin Pierce in support of Pierce’s 1852 presidential campaign, which was positively reviewed in the Democratic Review. Pierce who was the fourteenth president of the United States from 1853–1857, advocated US expansion for the purpose of opening markets and spreading American principles. According to the Democratic Party platform, “in view of the condition of popular institutions in the Old World, a high and sacred duty is devolved with increased responsibility upon the Democracy in this country.”[80]

Franklin Pierce (1804 – 1869), who was the 14th president of the United States from 1853–1857

Pierce was a northern Democrat who saw the abolitionist movement as a fundamental threat to the unity of the nation. He would alienate anti-slavery groups by supporting and signing the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act. The Kansas–Nebraska Act was drafted by Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by Pierce. Douglas introduced the bill with the goal of opening up new lands to development and facilitating construction of a transcontinental railroad. But the act is most notable for effectively repealing the Missouri Compromise, that admitted Maine to the United States as a free state, simultaneously with Missouri as a slave state, thus maintaining the balance of power between North and South in the US Senate. The signing of the act stoked national tensions over slavery, and contributed to the “Bleeding Kansas,” a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory between 1854 and 1861, which emerged from a political and ideological debate over the legality of slavery in the proposed state of Kansas. The Fugitive Slave Act was passed by the United States Congress in 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern slave-holding interests and Northern Free-Soilers. Yet, Pierce failed to stem conflict between North and South, setting the stage for Southern secession and the American Civil War.

Young America

Lajos Kossuth Arrives at Southampton Docks (1851)

Louis Kossuth (1802 – 1894)

George Sanders was in Europe during the Revolutions of 1848 and fought alongside of the Communists at the barricades in Paris in 1848. George Law and the Rothschild agent, August Belmont, financers of many Young America initiatives, acquired a financial interest in the Democratic Review in 1851 and appointed Sanders as its editor. Sanders was a supporter of President Polk and was later awarded the position of Consul in London during Pierce’s administration. The Democratic Review promoted the invasion Europe and Cuba and other Young America initiatives. While in London, Sanders served as the London correspondent for the New York Herald newspaper run by Young America editor, James Gordon Bennett, who wanted to expand the United States into Cuba, Canada, and the West Indies by force. Sanders needed to be recalled after he became involved in revolutionary and anarchist causes, having supposedly been involved in plans to assassinate heads of state, including the enemy of the Carbonari, French Emperor Napoleon III.

In 1952, Mazzini sent Louis Kossuth and his right-hand man Adriano Lemmi (1822 – 1896)—also a Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy and successor as head of the Palladian Rite—to the United States to organize Young America lodges. Kossuth was a Hungarian nobleman who served as Governor-President of the Kingdom of Hungary during the revolution of 1848–49. Known for his talent in oratory, the influential American journalist Horace Greeley (1811 – 1872) said of Kossuth: “Among the orators, patriots, statesmen, exiles, he has, living or dead, no superior.”[81] According to Friedrich Engels:

For the first time in the revolutionary movements of 1848, for the first time since 1793, a nation surrounded by superior counterrevolutionary forces dares to counter the cowardly counterrevolutionary fury by revolutionary passion, the terreur blanche by the terreur rouge.

For the first time after a long period we meet with a truly revolutionary figure, a man who in the name of his people dares to accept the challenge of desperate struggle, who for his nation is Danton and Carnot in one person—Lajos Kossuth.[82]

In 1849, Kossuth issued the celebrated Hungarian Declaration of Independence from the Habsburg Monarchy during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, and he was appointed regent-president. However, in response to the intervention of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, who was an opponent of revolution, and the failure of appeals to the western powers, Kossuth abdicated. Kossuth then first fled to the Ottoman Empire and finally arrived in England in 1851. After his arrival, the press characterized the atmosphere of the streets of London as this: “It had seemed like a coronation day of Kings.”[83] Many leading British politicians tried without success to suppress the so-called “Kossuth mania.” Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston, a supporter of the revolutions of 1848, intended to receive Kossuth, but it was prevented by a vote in Cabinet. Instead received a delegation of Trade Unionists from Islington and Finsbury and listened sympathetically as they read an address that praised Kossuth and declared the Emperors of Austria and Russia “despots, tyrants and odious assassins.”[84] That, together with Palmerston’s support of Louis Napoleon, caused the fall of the government of Lord Russell.[85]

From Britain Kossuth went to the United States of America. Kossuth completed a tour of several Masonic lodges to educate the Masonic hierarchy on how to recruit, organize, and train the youth in revolutionary strategy.[86] In the same year, Kossuth made contact with Pierce, offering him the propaganda services of Young America to promote his bid for the presidency in return for appoint particular individuals to important posts. Earlier in the year, the New York Herald reported that Pierce was a “discreet representative of Young America.”[87] Mazzini confirmed in his diary that Pierce was willing to accept help from Kossuth and his network of Masonic operatives: “Kossuth and I are working with the very numerous Germanic element [Young America] in the United States for his [Pierce’s] election, and under certain conditions which he has accepted.”[88] Pierce appointed several Young Americans to the foreign service: George Sanders as Consul to London; Nathaniel Hawthorne as Consul to Liverpool; James Buchanan as Minister to the Court of St. James, Great Britain; Pierre Soulé as Minister to Spain; John L. Sullivan as Minister to Portugal; and Edwin DeLeone as Consul to Egypt. Mazzini wrote, almost all his nominations are such as we desired.”[89]

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (1837 – 1913)

President Pierce’s first appointment was Freemason Caleb Cushing (1800-1879), who as U.S. attorney general became the master-architect of the Civil War. Cushing was connected to English Freemasonry by his affiliation with the Northern Jurisdiction of Freemasonry. His first Masonic assignment was to transfer money from British Masonic banker George Peabody to the Young America abolitionists, who after the elections were calling for the dissolution of the Union.[90] Peabody, who owned a giant banking firm in England, hired the services of J.P. Morgan, Sr. (1837-1913) to handle the funds as they arrived in the United States. Upon Peabody’s death, Morgan took over the firm and later moved it from England to the United States, renaming it Northern Securities. In 1869, Morgan went to London and reached an agreement to act as an agent for the N.M. Rothschild Company in the United States.

The handler of the Peabody funds in London was George Nicholas Sanders. At his home in London on February 21, 1854, Saunders hosted a dinner party with guests of honor being Mazzini, Blanqui, Kossuth and Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin (1807 – 1874), a French member of Carbonari. It was the speeches of Ledru-Rollin and Louis Blanc at working-men's banquets in Lille, Dijon and Chalons that heralded the revolution of 1848. Also in attendance were General Giuseppe Garibaldi; Felice Orsine, one of Mazzini’s contract terrorists and assassins; and Alexander Herzen of Russia, the man who initiated Freemason Mikhail Bakunin into Mazzini’s Young Russia; and Arnold Ruge, who with Karl Marx was the editor of a revolutionary magazine for Young Germany.[91] George Sanders gave the toast: “To do away with the Crowned Heads of Europe.”[92]

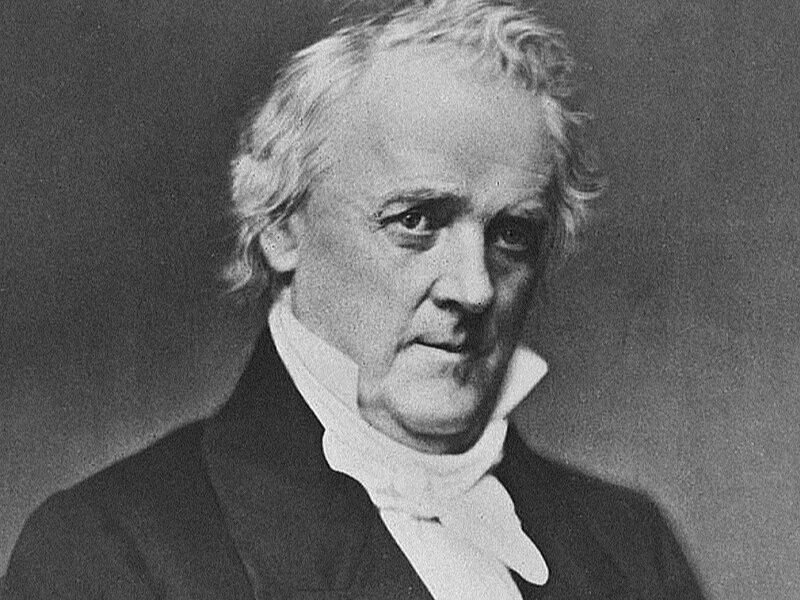

Also present at that meeting was President Pierce’s US Ambassador to England, Freemason James Buchanan (1791 – 1868), who would soon become the next president of the United States. In 1845, Buchanan had been appointed to serve as President Polk’s Secretary of State. Belmont served as campaign manager in New York for James Buchanan, then serving as an American diplomat in Europe, who was running for the Democratic Party’s nomination for president in the election of 1852. But when Pierce won the Democratic nomination and was elected President instead, he appointed Buchanan as his Minister to the United Kingdom, and August Belmont made further large contributions to the Democratic cause. In 1853, Pierce appointed Belmont Chargé d’affaires to The Hague of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Belmont had been taken under the wing of his wife’s uncle, John Slidell, a staunch defender of slavery as a Representative and Senator, who made Belmont his protégé.[93] Belmont helped organize the Democratic Vigilant Association, which sought to promote unity by promising Southerners that New York businessmen would protect the rights of the South and keep free-soil members out of office, who were largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into the western territories of the United States.[94]

James Buchanan Jr. (1791 – 1868)

With the support of Sanders, Buchanan was nominated in 1856 as president for the Democratic Party. When he was elected president, the Encyclopedia Americana relates, “Buchanan strongly favored the maintenance of slavery; his Cabinet was composed largely of advocates of the system, and he publicly supported proslavery elements…”[95] Buchanan was an advocate of states’ rights and for minimizing the role of the federal government in the nation’s closing era of slavery. He is therefore consistently ranked by historians as one of the least effective presidents in history, for his failure to mitigate the national disunity that led to the American Civil War. In his famous “House Divided” speech of June 1858, Abraham Lincoln charged that Douglas, Buchanan, his predecessor Pierce, and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney were all part of a plot to nationalize slavery, as allegedly proven by the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857.[96] Dred Scott v. Sandford was a landmark decision in which the Supreme Court held that the US Constitution was not meant to include American citizenship for black people, regardless of whether they were enslaved or free, and so the rights and privileges of the Constitution could not apply to them.

As a delegate to the pivotal 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina, Belmont supported Douglas, who had triumphed in the famous 1858 Lincoln-Douglas Debates over his long-time political rival, the newly recruited Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln, in their battle for Douglas’ Senate seat. Douglas subsequently nominated Belmont as chairman of the Democratic National Committee. Belmont also used his influence with European business and political leaders to support the Union cause in the Civil War, trying to dissuade the Rothschilds and other French bankers from lending funds or credit for military purchases to the Confederacy and meeting personally in London with the British prime minister, Lord Palmerston, and members of Emperor Napoleon III's French Imperial Government in Paris.[97] The Confederates had offered the states of Louisiana and Texas to Napoleon III if he would send troops against the North.

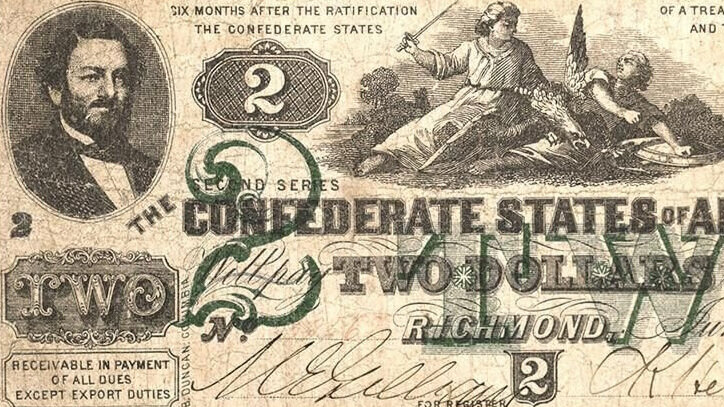

On November 8, 1861, the Union Navy set off a diplomatic incident known as the Trent Affair, illegally captured Slidell and James Murray Mason. The two were travelling as envoys bound for Britain and France to press the Confederacy’s case for diplomatic recognition and to lobby for possible financial and military support. Slidell’s daughter married Baron Frederic Emile d’Erlanger, from Erlanger & Cie, the Jewish bankers who headed the most distinguished banking house in France. Erlanger & Cie offered to float a loan to benefit the Confederacy. Baron d’Erlanger journeyed to Richmond in early 1863, and negotiated with Benjamin acting on behalf of the Confederacy, which he felt would provide the Confederacy with badly needed funds to pay its agents in Europe.[98] The crisis brought the US and Britain to the brink of war, but was resolved by their release.

Knights of the Golden Circle

Albert Pike (1809 – 1891)

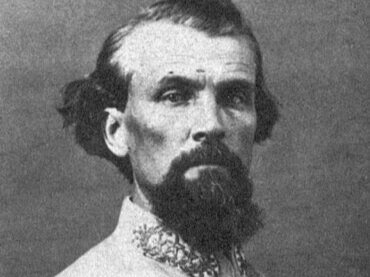

Strong evidence also suggests that Albert Pike was the secret brains behind the influence and power of the Masonic-influenced Knights of the Golden Circle, from which emerged the Ku Klux Klan.[99] Pike, Cushing’s nominee, was elected to take his place and became leader of the Southern secessionists.[100] At the same time, Cushing prepared for the British control of the Southern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry. In 1853, two weeks after Cushing was appointed attorney general, he sent Pike to Charleston to receive the higher Masonic degrees from Albert Gallatin Mackey. In 1857, Pike received the 33º degree in New Orleans, and in 1859 he was elected Sovereign Grand Commander of the Supreme Council of the Southern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry. In 1859, Pike was elected Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite’s Southern Jurisdiction. Pike now became the most powerful Mason in the world, occupying simultaneously the positions of Grand Master of the Central Directory at Washington, D.C., Grand Commander of the Supreme Council at Charleston, South Carolina, and Sovereign Pontiff of Universal Freemasonry.[101] Pike was regarded as the man most responsible for the growth and success of the Scottish Rite from an obscure Masonic Rite in the mid-nineteenth century to the international fraternity that it became. Pike remained Sovereign Grand Commander for the remainder of his life, devoting a large amount of his time to developing the rituals of the order.

The Northern Jurisdiction was still under the British spy and 33rd-degree Freemason John J.J. Gourgas. The English Masons sent Gourgas to New York to organize clandestine Scottish Rite lodges that would appear to be pro-French but would in fact were pro-English to help Britain in the War of 1812. In the summer of 1813, Emanual de la Motta, one of the founders of the Supreme Council of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite in Charleston, and a congregant of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, the colony’s first synagogue, reached a territorial agreement with Gourgas whereby the northern area was under the English Northern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry and based in Boston, while Charleston became the base for the French Southern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry. In 1854, Gourgas is said to have helped Killian Van Rensselaer founded a secret society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC), in Cincinnati, Ohio.[102] The seal of the KGC featured a Maltese cross used by the old Knights of Malta. The Golden Circle immediately absorbed the Freemasons working within Young America and became the Confederacy’s military pre-organization.[103] The self-styled Kentucky Gen. George W.L. Bickley (1819–1867), a Young American, took control of the KGC which advanced the societies goals of Manifest Destiny.[104]

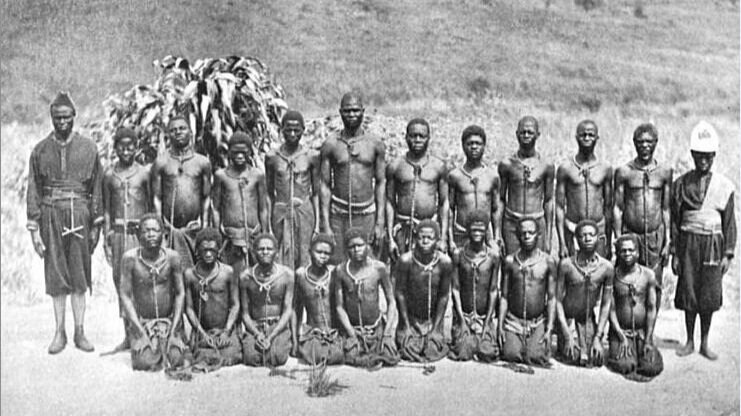

As abolitionism in the United States increased after the Dred Scott Decision of 1857, members of the KGC, inspired by the philosophies of Calhoun, proposed a separate confederation of slave states, with U.S. states south of the Mason-Dixon line to secede and to align with other slave states to be formed from the “golden circle.” Benson J. Lossing, author of Civil War in America, published in 1866, wrote, “It is authoritatively asserted that it was founded by John C. Calhoun and other South Carolina conspirators, in the year 1835.”[105] By the year 1834, in Charleston, New Orleans, and some other Southern cities, there were a few politicians who earnestly desired the re-establishment of the African slave-trade and the acquisition of new slave territory. These men formed themselves into Southern Rights Clubs.[106] They had certain signs of recognition, by which they made themselves known to each other. Most of the KGC’s rituals were borrowed from Freemasonry and later from the Knights of Pythias. Some members were also said to be Rosicrucians.[107] They supposedly amassed huge wealth for the purpose of restarting the Civil War.[108] It has been said of the KGC “that they were one of the deadliest, wealthiest, most secretive and subversive spy and underground organizations in the history of the world.”[109]

Gen. George W.L. Bickley (1819 – 1867)

Another scheme for an expanded southern empire took place in 1859, when Bickley took control of the KGC for plan to annex a “golden circle” of territories around the Gulf of Mexico, covering Central America, Confederate States of America, and the Caribbean as slave states, to be led by Maximilian I of Mexico. This would have resulted in the addition of 25 new slave states and monopolized the world’s sugar, tobacco and slave trades. Havana, Cuba, the geographical center of this vast “golden circle,” would become its capital. Bickley was the organization’s leading promoter and chief organizer for the KGC lodges, called “Castles,” in several states. All the Grand State Castles were represented by delegates in what was named the Grand United States or American Legion.[110]

One castle was opened by John A. Quitman (1798 –1858) in Jackson, Mississippi, and another by Albert Pike in New Orleans. Bickley claimed more than 100,000 members, mostly from Texas.[111] Quitman (1798 –1858), a protégé of John C. Calhoun, was the father of Mississippi Freemasonry and leader of the southern secessionists, was the representative from Mississippi in the House of Representatives. He was initiated to the Scottish Rite Masonry till his elevation to the 33rd and highest degree. Quitman was slated to be the next Sovereign Grand Commander of the Southern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry, but on July 17, 1858, he suddenly died by poisoning, according to Masonic authority.[112]

From its earliest origins in the Southern Rights Clubs in 1835, the KGC was to become “the most powerful secret and subversive organization in the history of the United States with members in every state and territory before the end of the Civil War.”[113] One of the recruits initiated into the Knights of the Golden Circle was General and Freemason P.T. Beauregard (1818-1893), a West Point graduate of 1838, and brother-in-law of John Slidell. Beauregard is credited with starting the Civil War with his surprise attack on Fort Sumter in 1861. On 12 April 1861 General Beauregard, was ordered to make a surprise attack on US-held Fort Sumter, and thus began the Civil War.[114]

The inauguration of President Jefferson Davis of the Confederate States of America on Feb. 18, 1861, in Montgomery, Alabama

Jefferson Finis Davis (1808 – 1889)

The South had begun to secede from the Union in January 1861, and in February of that year, seven seceding states ratified the Confederate Constitution and named Freemason Jefferson Davis as provisional president. Davis fought in the Mexican–American War as the colonel of a volunteer regiment. Pierce appointed him as Secretary of War. There are several indications that Davis was active in the network of the Carbonari.[115] Before the American Civil War, he operated a large cotton plantation in Mississippi, which his brother Joseph gave him, and owned as many as 113 slaves.[116] Davis married Sarah Knox Taylor, the daughter of General Taylor. Her brother, Richard Taylor (1826 – 1879), a Confederate general, was a member of Skull and Bones, as was Davis’s private secretary Burton Norville Harrison (1838 – 1904).[117]

Many Southerners believed Calhoun’s warnings of the planned destruction of the white southern way of life. The climax came a decade after Calhoun’s death with the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860, which led to the secession of South Carolina, followed by six other Southern states. The KGC became the first and most powerful ally of the newly-created Confederate States of America, commonly referred to as the Confederacy and the South.[118] The Confederacy was originally formed by seven secessionist slave-holding states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—in the Lower South region of the United States, whose economy was heavily dependent upon agriculture, particularly cotton, and a plantation system that relied upon the labor of African-American slaves. They formed the new Confederate States, which, in accordance with Calhoun's theory, did not have any organized political parties.[119] Each state declared its secession from the United States, which became known as the Union during the ensuing civil war, following the November 1860 election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln to the U.S. presidency on a platform which opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories.

Mystick Krewe of Comus

New Orleans Mardis Gras

Mimi L. Eustis published a website in 2005, titled Mardi Gras Secrets, to share the deathbed confessions of her father Samuel Todd Churchill, a high-level member of the Mystick Krewe of Comus, a secret society founded in 1856 by Judah P. Benjamin and Albert Pike in order to meet and communicate the plans of the Rothschilds. The Mystick Krewe of Comus, which is named after John Milton’s Lord of Misrule in his masque Comus, is oldest continuous organization of New Orleans Mardi Gras, a modern adaptation of the Feast of Fools festival. Prior to the advent of Comus, Carnival celebrations in New Orleans were mostly confined to the Roman Catholic Creole community, and parades were irregular and often very informally organized.

The Mardi Gras was originally a Catholic festive season that occurs before the liturgical season of Lent. From Italy, Carnival traditions spread to Spain, Portugal, and France, and from France to New France in North America. From Spain and Portugal, it spread with colonization to the Caribbean and Latin America. Most Louisiana cities which were under French control at one time or another, also hold Carnival celebrations. The most widely known, elaborate, and popular US events are in New Orleans where Carnival season is referred to as Mardi Gras.

Although officially, the Krewe of Comus claims to descend from the Cowbellion de Rakin Society of Mobile, Alabama, Eustis’ father claimed the society was founded by Yankee bankers from New England, who used the society as a front for the House of Rothschild, as well as for Skull and Bones, which was a branch of the Bavarian Illuminati. Passage into the secret of the code number 33, the highest stages of membership within the Skull and Bones society, required participation in the ritual “Killing of the King.” Eustis says her father emphasized that most Masons below the 3º remained in ignorance, while those to who rose past the 33º did so by participating in the “Killing of the King” ritual.

According to Eustis, William H. Russell, the founder of Skull and Bones, had a key partner by the name of Caleb Cushing, who served as a U.S. Congressman from Massachusetts and Attorney General under President Franklin Pierce. Cushing was involved in the secret “Killing of the King” of Presidents William Henry Harrison (1773 –1841) in 1841, and Zachary Taylor (1784 – 1850) in 1850, who had both opposed admitting Texas and California as slave states. Cushing dispatched Albert Pike, where his mission was to further the cause of slavery and to foster the Civil War, and to establish a line of communication with other fellow Illuminati. Pike was chosen by Cushing to head an Illuminati branch in New Orleans and to establish a New World order. Pike moved his law office to New Orleans in 1853 and was made Masonic Special Deputy of the Supreme Council of Louisiana on April 25, 1857.

Cushing, recounted Eustis, dispatched Albert Pike to Arkansas and Louisiana. Pike’s mission was to further the cause of slavery and to foment a and America civil war, and to establish a line of communication with other fellow Illuminati. Pike was chosen by Cushing to head an Illuminati branch in New Orleans and to establish a New World order. Pike moved his law office to New Orleans in 1853 and was made Masonic Special Deputy of the Supreme Council of Louisiana on April 25, 1857. Eustis further asserts, Pike and Judah P. Benjamin needed a secret society in order to foster a civil war in the United States and to establish the House of Rothschild, for which purpose they founded the Mystick Krewe of Comus in that same year.

The Mystick Krewe of Comus was founded to observe Mardi Gras in a more organized fashion. The second-oldest krewe in the New Orleans Mardi Gras is the Krewe of Momus, Son of Night & Lord of Misrule, which was founded in 1872. The Knights of Momus has operated continuously since its founding, and remains a secret society. The 1877 parade theme, “Hades, A Dream of Momus,” caused an uproar when it took aim at the Reconstruction government established in New Orleans after the Civil War. Attempts at retribution by local authorities were largely unsuccessful due to the secrecy of the membership. Momus’s 1878 float was inspired by Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Young American Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804 – 1864)

The inspiration for the Krewe of Comus came from Rosicrucian author John Milton’s Lord of Misrule in his masque Comus. The rebellious Thomas Morton declared himself “Lord of Misrule” during the pagan revelry in Merrymount in 1627, and his fellow celebrants were described by Young American Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804 – 1864) in The May-Pole of Merry Mount (1837) as a “crew of Comus.” Hawthorne was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, where his ancestors included John Hathorne, the only judge involved in the Salem witch trials who never repented of his actions. Much of Hawthorne’s fiction, such as The Scarlet Letter is set in seventeenth-century Salem. In 1851, Hawthorne published The House of the Seven Gables, a Gothic novel whose setting was inspired by the Turner-Ingersoll Mansion, a gabled house in Salem, belonging to Hawthorne’s cousin Susanna Ingersoll, and by his ancestors who had played a part in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. In Young Goodman Brown, the main character is led through a forest at night by the Devil, appearing as man who carries a black serpent-shaped staff. Goodman is led to a coven where the townspeople of Salem are assembled, including those who had a reputation for Christian piety, in-mixed with criminals and others of lesser reputations, as well as Indian priests. Herman Melville said the novel was “as deep as Dante” and Henry James called it a “magnificent little romance.”[120]

Edgar Allan Poe, a fellow contributor to the Democratic Review, referred to Hawthorne’s short stories as “the products of a truly imaginative intellect.”[121] Poe’s gothic works are replete with occult symbolism. Poe’s Cask of Amontillado enacts a Masonic ritual in a way that would be evident only to Masons. The story is set in an unnamed Italian city, told from the perspective of a man named Montresor plots to murder his friend Fortunato during Carnevale (Mardi Gras), while the man is drunk and wearing a jester’s motley. who, he believes, has insulted him. According to Robert Con Davis-Undiano, “the plot of story, from Montresor’s initial meeting with Fortunato during Italian Carnevale, through Fortunato’s final entombment, itself enacts an initiation rite for Freemasonry.”[122]

Jewish Confederate