4. Eugenics and Sexology

Fabian Society

The idea of a modern project of improving the human population, through a statistical understanding of heredity used to encourage good breeding, was originally developed by Francis Galton and, initially, was closely linked to Darwinism and his theory of natural selection. Assessing the work of Charles Darwin, and considering the experience of animal breeders and horticulturists, Galton wondered if the human genetic pool could be improved: “The question was then forced upon me—Could not the race of men be similarly improved? Could not the undesirables be got rid of and the desirables multiplied?”[1] Galton’s concept of soon won many adherents, notably in North America and England, particularly among members of the Fabian Society, the British socialist organization founded in 1884. The purpose of the Fabian Society was to advance the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. At the core of the Fabian Society were Sidney and Beatrice Webb, who co-founded the London School of Economics. Leading Fabians included Bertrand Russell, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells and Aldous’s brother Julian Huxley. Shaw revealed that their goal was to be achieved by “stealth, intrigue, subversion, and the deception of never calling socialism by its right name.”[2]

George Bernard Shaw (1856 – 1950)

The Fabian Society was as a splinter group of the Fellowship of the New Life, composed of artists and intellectuals, which included Annie Besant and also members of the Society for Psychical Research. Fellowship members included Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor, Edward Carpenter, George Bernard Shaw, Havelock Ellis and H.P. Blavatsky’s successor Annie Besant. Carpenter, Walt Whitman’s homosexual lover, was a leading figure in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain, and corresponded with many famous figures such as Isadora Duncan, Mahatma Gandhi, Jack London, William Morris and John Ruskin. Carpenter was also instrumental in the foundation of the Fabian Society and the Labour Party.

Annie Besant was a leading speaker for the society. Besant’s interest in socialism was sparked through her relationship with George Bernard Shaw, who considered Besant to be “The greatest orator in England.” During 1884, Besant had developed a very close friendship with Edward Aveling, who first translated the works of Marx into English. Aveling eventually went to live with Marx’s daughter Eleanor Marx. Aveling and Eleanor had joined the Marxist Social Democratic Federation and then the Socialist League, a small Marxist splinter group which formed around the artist William Morris. It seems that Morris played a large part in converting Besant to Marxism.[3] Eliza Doolittle in Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion (1914) and the later film My Fair Lady was based on William Morris’s wife Jane.

H.G. Wells (1866 – 1946), author of War of the Worlds

In addition to Nehru, several pre-independence leaders in colonial India such as Jawaharlal Nehru (1889 – 1964) later the first Prime Minister of India, were members of the Fabian Society. Both Nehru and Gandhi spoke of Besant’s influence with admiration.[4] As a child, under the influence of a tutor, Ferdinand T. Brooks, Nehru became interested in theosophy and was initiated into the Theosophical Society at age thirteen by family friend Besant. Nehru went to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1907 and studied the writings of Shaw, Wells, Keynes and Russell.[5] After completing his degree in 1910, Nehru moved to London and studied law at Inner temple Inn, and continued to study the scholars of the Fabian Society including Beatrice Webb.[6]

According to Shaw, “the most thoroughgoing opponents of our existing state of society” declared themselves followers not of Karl Marx but of John Ruskin, the English art critic, Social Darwinist, Freemason, occultist and pedophile, who inspired Cecil Rhodes imperialistic ambitions.[7] Ruskin first came to widespread attention with the first volume of Modern Painters in 1843, in which he argued that the principle role of the artist is “truth to nature.” Theorists and practitioners in a broad range of disciplines acknowledged their debt to Ruskin. Architects including Le Corbusier, Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright (who married Gurdjieff’s former lover Olga Ivanovna Hinzenberg) and Walter Gropius incorporated Ruskin’s ideas in their work. Writers as diverse as Oscar Wilde, G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats and Ezra Pound felt Ruskin’s influence.

Aldous Huxley (1894 – 1963), author of Brave New World, and brother Julian Huxley (1887 – 1975)

Bertrand Russell (1872 – 1970)

The Huxleys came from a family of eugenicists and ardent defenders of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Huxley’s grandfather, Thomas Henry Huxley (1825 –1895), was known as “Darwin’s Bulldog.” It was Thomas Henry Huxley who coined the term “Darwinism” in his March 1861 review of On the Origin of Species, and by the 1870s the term opened the way to the interpretations of “Social Darwinism,” when it was used to apply biological concepts of “natural selection” and “survival of the fittest” to sociology and politics. Despite the fact that Social Darwinism bears Charles Darwin’s name, it is also linked today with others, notably Herbert Spencer, Thomas Malthus, and Francis Galton, the founder of eugenics.

Aldous Huxley was widely acknowledged as one of the pre-eminent intellectuals of his time.[8] He was nominated seven times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. After studying at Balliol, Oxford, Huxley taught French at Eton, where George Orwell and Stephen Runciman were among his pupils. During World War I, Huxley spent time among the Bloomsbury Group. Huxley was also involved in the Fabian Society and along with his student George Orwell, he was the protégé of H.G. Wells.

The first Fabian Society pamphlets advocating tenets of social justice also advanced eugenics, advocating the ideal of a scientifically planned society and supported eugenics by way of sterilization.[9] According to H.G. Wells:

We cannot go on giving you health, freedom, enlargement, limitless wealth, if all our gifts to you are to be swamped by an indiscriminate torrent of progeny… and we cannot make the social life and the world-peace we are determined to make, with the ill-bred, ill-trained swarms of inferior citizens that you inflict upon us.[10]

“Beneath their seemingly compassionate rhetoric,” wrote Dennis Sewell in the New Spectator, “the founders of the Fabian Society were snobbish, elitist and harboured a savage contempt for the poorest of the poor.”[11] At the peak of its popularity, eugenics was supported by a wide variety of prominent people including, Winston Churchill, Theodore Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, and a disproportionate number of Fabians, including Havelock Ellis, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, John Maynard Keynes and Sidney Webb, and others influenced by them, like sexologist Norman Haire and sex educators Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Even for George Bernard Shaw, “the only fundamental and possible Socialism” was “the socialisation of the selective breeding of Man.”[12] Beatrice Webb declared eugenics to be “the most important question of all” while her husband Sydney remarked that “no eugenicist can be a laissez-faire individualist.”[13]

Beatrice and Syndey Webb

The field adapted to psychiatry the concepts of eugenics, or more specifically, race purification, race hygiene, or race betterment developed in London’s Galton Laboratory and its sister eugenics societies in England and America. Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities and received funding from many sources. In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations.

Eugenics was supported through extensive financing by corporate philanthropies, specifically the Carnegie Institution, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Harriman railroad fortune.[14] They were all in league with many of America’s most respected scientists at the time, hailing from prestigious universities such as Stanford, Yale, Harvard, and Princeton. Stanford president David Starr Jordan originated the notion of “race and blood” in his 1901 thesis “The Blood of the Nation: A Study in the Decay of Races by the Survival of the Unfit,” published in Popular Science Monthly.

The government under Theodore Roosevelt created a national Heredity Commission in 1906 that was charged to investigate the genetic heritage of the country and to “(encourage) the increase of families of good blood and (discourage) the vicious elements in the cross-bred American civilization.”[15] Roosevelt wrote to a prominent eugenicist named Charles Davenport that “society has no business to permit degenerates to reproduce their kind. It is really extraordinary that our people refuse to apply “to human beings such elementary knowledge as every successful farmer is obliged to apply to his own stock breeding.”[16] Charles Davenport supported by the Carnegie Institution established the Eugenics Record Office, a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity research from 1910 to 1939.[17]

Madison Grant (1865 – 1937)

Roosevelt was a friend of Madison Grant, an American lawyer, known primarily for his The Passing of the Great Race (1916), a book espousing scientific racism, which played an active role in crafting strong immigration restriction and anti-miscegenation laws in the United States. According to Grant: “[I]f the valuable elements in the Nordic race mix with inferior strains or die out through race suicide, then the citadel of civilization will fall for mere lack of defenders.”[18] Hitler would write to him, complimenting Grant for what he called “my bible.”[19]

Working with the eugenicists of the Fabian Society of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Lord Balfour— Round Table member and later Prime Minister, known for the Balfour Declaration—founded the first International Eugenics Conference in 1912 alongside a young Winston Churchill, First Lord of the British Admiralty. Charles Darwin’s cousin and founder of eugenics, Sir Francis Galton died mere weeks before being able to keynote the conference. Major Leonard Darwin, the son of Charles Darwin, was presiding. Luminaries included Lord Alverstone, as well as the ambassadors of Norway, Greece, and France. By its end, the Congress had established a Permanent International Eugenics Committee, over which Darwin was named president. In 1921, the Committee arranged for the second meeting of the International Eugenics Congress to take place, led by Henry Fairfield Osborn, Madison Grant, and Clarence Little. In 1925, the Committee was renamed the International Federation of Eugenic Organizations (IFEO), where Charles Davenport was a dominant force.

Nazi eugenics actually began in the United States, and emerged in Germany under Rockefeller funding. After World War I, the Rockefeller Foundation began funding a medical specialty known as psychiatric genetics in Germany. In 1917, the Rockefeller Foundation created the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Psychiatry in Munich (formerly known as the Kraepelin Institute) and in 1927, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Eugenics and Human Heredity in Berlin. The Kraepelin institute had initially been endowed by Paul Warburg’s brother-in-law James Loeb, of the Kuhn-Loeb banking family, and Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, head of the Krupp family. The institute was named after Emil Kraepelin (1856 –1926), who is considered the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, as well as of psychopharmacology and psychiatric genetics.[20] The theories of Kraepelin, whom Freud nicknamed “the super-pope” of psychiatry, dominated the subject at the start of the twentieth century, although he was eventually overshadowed by the reception of Freud.[21]

Society for Psychical Research

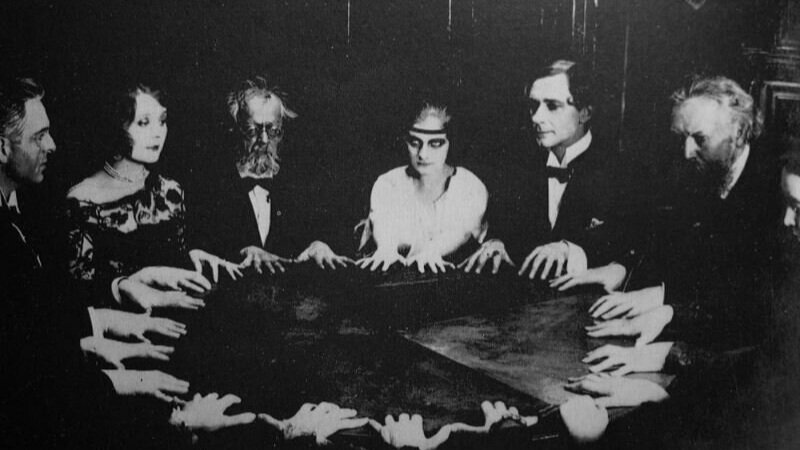

A seance scene from the 1922 film Dr. Mabuse the Gambler.

William James (1842 – 1910)

Fabian Society member Bertrand Russell, along with Arthur Conan Doyle, Lord Balfour, John Dewey and John Ruskin was a member of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), a non-profit organization founded in 1882 for the stated purpose of understanding “events and abilities commonly described as psychic or paranormal by promoting and supporting important research in this area” and to “examine allegedly paranormal phenomena in a scientific and unbiased way.” In 1884, William James became a founding member of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) and, in 1894 and 1895, a president of the SPR, and he reviewed and defended the work of the SPR in psychology and science periodicals like Mind, the Psychological Review, Nature and Science.

As indicated by Andreas Sommers, at the end of the nineteenth century, largely unacknowledged by historians of the human sciences, psychical researchers were actively involved in the development of the emerging science of psychology. “While rooted in attempts to test controversial claims of telepathy, clairvoyance and survival of death,” explains Sommer, “these contributions enriched early psychological knowledge quite independently of the still hotly debated evidence for ‘supernormal’ phenomena.”[22] For the most part, as Sommers has indicated, historians have failed to assess the wider implications of the fact that William James, the founder of academic psychology in America, considered himself a psychical researcher and sought to assimilate the scientific study of mediumship, telepathy and other paranormal subject into the new field. Joseph Jastrow, one of the founding members of the American Society for Psychical Research, reminisced about the problem of psychical research, “which in the closing decades of the nineteenth century was so prominent that in many circles a psychologist meant a ‘spook hunter’.”[23]

Albert Freiherr von Schrenck-Notzing (1862 – 1929)

Despite the association of several of its members with Theosophy, it was the SPR which later investigated Blavatsky’s mysterious Mahatma letters which were said to appear out of thin air and in 1885 declared her to be a fraud. It has been suggested that the hasty attempt to found a German branch of the Theosophical Society sprang from Blavatsky’s desire for a new center after a scandal involving charges of charlatanism against the theosophists at Madras early in 1884 by Richard Hodgson of the SPR.[24] The German Theosophical Society, to which belonged Franz Hartmann and Rudolf Steiner, was founded by Wilhelm Hübbe-Schleiden, an associate of Henry Steel Olcott and Annie Besant.

Max Dessoir (1867 – 1947)

Hübbe-Schleiden was a founding member of the German Gesellschaft für psychologische Forschung (“Society for Psychological Research”), co-founded in 1890 with Albert Freiherr von Schrenck-Notzing (1862 – 1929) and Max Dessoir (1867 – 1947).[25] The Gesellschaft was an amalgamation of two previously existing associations, the Psychologische Gesellschaft (“Psychological Society”) in Munich, cofounded by Schrenck-Notzing, and the Gesellschaft für Experimental-Psychologie (“Society of Experimental Psychology”) in Berlin under the leadership of Max Dessoir. Both organizations were founded as psychical research societies similar to the SPR in England, whose research program, which included studies of telepathy, apparitional experiences, mediumship, and hypnotism, they attempted to emulate.

Dessoir was a member of the SPR.[26] Dessoir, who was born in Berlin into a German Jewish family, was an associate of Pierre Janet and Freud. According to Sommer, Dessoir and Schrenck-Notzing closely followed the example of William James by acting as conduits for French and English strands of experimental psychology.[27] Dessoir was an amateur magician who had used the pseudonym “Edmund W. Rells,” and was interested in the history and psychology of magic. Dessoir is also known for his coinage of the term “Parapsychologie” in an attempt to delineate the scientific study of a certain class of “abnormal,” though not necessarily pathological mental phenomena. He published a series of articles entitled The Psychology of Legerdemain, which were printed in five weekly installments for the Open Court journal in 1893.[28] Dessoir was a professor at Berlin from 1897 until 1933, when the Nazis forbade him to teach.

Schrenck-Notzing and medium Eva Carrière

Schrenck-Notzing was a German medical doctor and a pioneer of psychotherapy and parapsychology, who had participated in Max Theon’s Cosmic Movement.[29] Schrenck-Notzing devoted his time to the study of paranormal events connected with mediumship, hypnotism and telepathy. He investigated spiritualist mediums such as Willi Schneider, Rudi Schneider, and Valentine Dencausse.[30] Also a witness to these experiments was author Thomas Mann, who detailed his experiences with Willy and Rudi Schneider in Okkulte Erlebnisse (“Occult Experiences”). Schrenck-Notzing investigated the medium Eva Carrière. Carrière was well known for running around the séance room naked indulging in sexual activities with her audience. During the course of the séance sittings with Schrenck-Notzing, her companion Juliette Bisson would put her finger into Eva’s vagina to ensure no “ectoplasm” had been placed there beforehand to deceived the investigators, and she would also strip nude at the end of a séance, demanding another full gynecological exam.[31] Carrière’s psychic performances were investigated by Arthur Conan Doyle, and Harry Houdini dismissed her performance as a magician’s trick, the Hindu needle trick.[32] Schrenck-Notzing, however, believed the ectoplasm she produced was real. However, Schrenck-Notzing theorized that her ectoplasm “materializations” did not have anything to do with spirits, but were the result of “ideoplasty” in which the medium could form images onto ectoplasm from her mind.[33]

Charles Richet (1850 – 1935) who coined the term “ectoplasm”

The foundation of the Psychologische Gesellschaft in 1886 was preceded in January of the same year by Hübbe-Schleiden’s periodical The Sphinx, which was a powerful influence in the German occult revival until 1895. Both Dessoir and Schrenck-Notzing were regular contributors. The focus of publication was the promotion of the “transcendental psychology” of Carl du Prel (1839 – 1899), a German philosopher and writer on mysticism and the occult, as outlined in his Philosophie der Mystik. According to Sommer, “It was owing to the purpose of establishing du Prel’s transcendental psychology, whose empirical foundations were research into dreams, mesmerism, somnambulism, and hypnotism, that The Sphinx became one of the most important—if not the most important—early German periodicals serving as a conduit for the latestworks in hypnotism from France and England.”[34]

According to Corinna Treitel, in A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern, “the coming together of de Prel and Schrenk-Notzing under the umbrella of the Pshychologische Gesellschaft of Munich in 1886 to 1889 was an important chapter in both the history of the mind/brain sciences and the emergence of the modern German occult movement.”[35] When the first International Congress of Physiological Psychology met in 1889, Schrenk-Notzing and his paranormal interests played a prominent role.[36] Attendees of the conference read like an who’s who in the new field of psychology. In addition to Schrenk-Notzing, Max Dessoir and William James, these included Charles Richet, Pierre Janet, Auguste Forel, Joseph Delbouef, Francis Galton, Frederick W.H. Myers, James’ student Hugo von Münsterberg, SPR member Henry Sidgwick and his wife Eleanor Balfour—the sister of Lord Balfour.

Also attending the conference was Cesare Lombroso (1835 – 1909), known for his theory of anthropological criminology, which essentially stated that criminality was inherited, and could be identified by congenital physical defects. In the early 1890s, Prof Charles Robert Richet (1850 – 1935), the president of the British SPR, invited Schrenck-Notzing to attend sittings with the notorious Italian medium Eusapia Paladino, who converted previous sceptics, such as Cesare Lombroso, Enrico Morselli and Pierre Curie to a belief in paranormal phenomena.[37] Richet was a French physiologist at the Collège de France known for his pioneering work in immunology. In 1913, he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “in recognition of his work on anaphylaxis.” Richet devoted many years to the study of paranormal and spiritualist phenomena, coining the term “ectoplasm.” Richet also believed in the inferiority of blacks, was a proponent of eugenics and presided over the French Eugenics Society towards the end of his life.

Eusapia Palladino and SPR founder Henry Sidgwick in Cambridge (1895)

Paladino claimed powers such as the ability to levitate tables, communicate with the dead through her spirit guide John King, and to produce other supernatural phenomena. Joseph Jastrow, in his book The Psychology of Conviction (1918), included a chapter denouncing Palladino as a fraud. Harry Houdini and Joseph Rinn also claimed her feats were conjuring tricks. Dessoir and Albert Moll of Berlin detected the precise substitution tricks that were used by Palladino. Dessoir and Moll wrote: “The main point is cleverly to distract attention and to release one or both hands or one or both feet. This is Paladino’s chief trick.”[38]

While Paladino would cheat whenever she was given the opportunity, she was nevertheless reported to have produced, sometimes under good conditions of experimental control, levitations and remote manipulations of objects, materializations of human forms and the development of bizarre pseudopodia. Many skeptical scientists who came to investigate her left as believers. For example, Cesare Lombroso, one of the chief enemies of psychical research and spiritualism in Italy, attended sittings with Palladino in the 1890s with the intent of exposing her, but left completely convinced and embraced the spirit hypothesis to explain some of these phenomena. Most other investigators of Palladino and other mediums, such as Charles Richet, Enrico Morselli, Théodore Flournoy and Schrenck-Notzing, however, rejected the spirit hypothesis and favored a psychodynamic explanation in terms of “teleplasty” or “ideoplasty,” describing the materializations as “externalized dreams” of physical mediums.[39]

Hugo Münsterberg, who worked on pro-German propaganda George Sylvester and Otto Kahn’s friend Hanns Heinz Ewers, who were all intimately acquainted with Aleister Crowley

The definitive blow to Paladino, and the credibility of mediums and seances in general, came with the Harvard psychologist Hugo Münsterberg (1863 – 1916), a student of William James and an attendee of the Paris conference. Münsterberg was born into a merchant family in Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland), then a port city in West Prussia. Even if he was later known for his German nationalism, Münsterberg’s family was actually Jewish.[40] Münsterberg was one of the pioneers in applied psychology. He was a student and research assistant of the University of Leipzig of Wilhelm Wundt (1832 – 1920), who is widely regarded as the "father of experimental psychology.”[41] In 1889, he met William James, who eventually invited him to Harvard for a three-year term as a chair of the psychology lab. As Crowley indicated, Münsterberg was “someone who had made a special study for years of the psychology of Americans,” a man of “ripe, balanced wisdom,” who as a teacher at Harvard had “acquired the habit of forming and directing minds.”[42]

With the help of a hidden man lying under a table, Münsterberg caught Paladino levitating the table with her foot.[43] Münsterberg’s report, originally published in the Metropolitan Magazine in 1910, reprinted with minor changes in American Problems in 1912, was summarized in the New York Times and many other papers across the country and beyond, and publicized in both the popular and scientific press as the final verdict on paranormal phenomena for public general in general.[44] Münsterberg’s conclusion was that, “Her greatest wonders are absolutely nothing but fraud and humbug; this is no longer a theory but a proven fact.”[45] At the same time, however, Münsterberg believed that Paladino might not be held fully responsible for her deceptions, proposing that it was “improbable that Madame Palladino, in her normal state is fully conscious of this fraud. I rather suppose it to be a case of complex hysteria in which a splitting of the personality has set in.”[46]

In 1912, the SPR extended a request for a contribution to a special medical edition of its Proceedings to Sigmund Freud. Though according to Ronald W. Clark, “Freud surmised, no doubt correctly, that the existence of any link between the founding fathers of psychoanalysis and investigation of the paranormal would hamper acceptance of psychoanalysis” as would any perceived involvement with the occult. Nonetheless, Freud did respond, contributing an essay titled “A Note on the Unconscious in Psycho-Analysis” to the Medical Supplement to the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research.[47]

Sigmund Fraud

Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939) and his daughter Anna

David Bakan, in Sigmund Freud and The Jewish Mystical Tradition, has shown that Freud too was a “crypto-Sabbatean,” which would explain his extensive interest in the occult and the Kabbalah. The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots, by Joseph H. Berke, explores Freud and his Jewish roots and demonstrates the input of the Jewish mystical tradition into Western culture through psychoanalysis. According to Dr. Sanford Drob, the Chabad psychology is, “an important precursor of Freud’s famous description of psychoanalytic cure.”[48] As Drob noted, while none of Freud’s biographers discuss Jewish religious influence on his work, they are unanimous in acknowledging that Freud’s sense of Jewishness was the single most important part of his personal background. Freud’s parents each came from towns in Galicia which was a center of Hasidism and learning. In a letter to a personal acquaintance, Freud described his father as coming from a Hasidic background. Freud’s great‑grandfather, Rabbi Ephraim Freud, and grandfather, Rabbi Shlomo Freud, were learned Hasidic Jews.[49]

Hippolyte Bernheim (1840 – 1919)

Maya Balakirsky Katz revealed that in consultation with Freud, the Viennese psychoanalyst Wilhelm Stekel (1868 – 1940) treated the sixth Chabad rebbe, Sholom DovBer Schneerson (1860 – 1920), commonly referred to as the Rashab. The Rashab confessed that a “man-servant,” whose tasks included watching over the rabbi as a child, sexually molested him from the time he was “five or six” until his marriage. The Rashab’s brother habitually took the rabbi into his wife’s bedroom, “where he displayed her in scant attire, with the idea of arousing him, and to hold his wife’s beauty before his eyes.” In his brother’s absence, the Rashab remained with his sister-in-law, playing with her and “having fun.” The Rashab occasionally wrestled with a friend in his wife’s presence, and, after successfully pinning his friend on the floor, the rabbi triumphantly took his wife to bed.[50]

Although he tried to keep it hidden during his lifetime, Freud too experimented with occult phenomena. In the late 1880s, Freud studied hypnotism under Hippolyte Bernheim (1840 – 1919) in Nancy, together with Wilhelm Hübbe-Schleiden. Bernheim was a Jewish physician and neurologist from France, chiefly known for his theory of suggestibility in relation to hypnotism.[51] Bernheim also had a significant influence on Freud, who had visited Bernheim in 1889, and witnessed some of his experiments. Freud would later refer to himself a pupil of Bernheim, and it was out of his practice of Bernheim’s suggestion and hypnosis that psychoanalysis would evolve.[52] Freud had already translated Bernheim’s On Suggestion and its Applications to Therapy in 1888, and later described how “I was a spectator of Bernheim’s astonishing experiments upon his hospital patients, and I received the profoundest impression of the possibility that there could be powerful mental processes which nevertheless remained hidden from the consciousness of man.”[53]

With his colleague Sandor Ferenczi, Freud visited a clairvoyant in Berlin in 1909. He also treated several patient who had consulted psychics for their phycological ills. In 1913, along with three other psychologists, he organized a séance in his own home. Although he was not entirely satisfied with the results, he could not entirely deny the reality of paranormal phenomena. Freud’s interest in the occult was finally exposed when an essay from 1921 about telepathy was published in 1941.[54] Freud eventually accepted the possibility of telepathic communication as psychoanalytic rather than occult phenomena, particularly as manifested in dreams.[55]

Lou Andreas-Salomé, Paul Rée and Nietzsche

Freud also read Nietzsche as a student and analogies between their work were pointed out almost as soon as he developed a following. Freud and Nietzsche had a common acquaintance in Lou Andreas-Salomé, a Russian-born psychoanalyst and author. Somewhat of a femme fatale, Andreas-Salomé also had an affair with Richard Wagner and Nietzsche. Salomé claimed that Nietzsche was desperately in love with her and that she refused his proposal of marriage to her. During her lifetime she achieved some fame with her controversial biography of Nietzsche, the first major study of his life. Salomé was a pupil of Freud and became his associate in the creation of psychoanalysis. Freud considered Salomé’s article on anal eroticism from 1916 one of the best things she wrote. This led him to his own theories about anal retentiveness.[56]

According to Frederick Crews, author of Freud: The Making of an Illusion, Freud was a money-obsessed, sex-crazed fraud. According to his ex-friend Wilhelm Fliess, “the reader of thoughts merely reads his own thoughts into other people.”[57] He writes how Freud would sexually assault his female patients, who would come away from his treatments in much worse condition. Crews deduces that as a teenager, while his parents were away and he was left in charge of his younger siblings, Freud sexually abused his younger sister. After Freud and his wife Martha’s sex life ended, he had an affair with her sister, Minna, who came to live with them when she was widowed. In what became the basis of his Oedipal Complex, Freud admitted he was in love with his mother: “I have found, in my own case, the phenomenon of being in love with my mother and jealous of my father, and I now consider it a universal event in early childhood.”[58]

Freud proposed that the Oedipus complex, which originally refers to the sexual desire of a son for his mother, is a desire for the parent in both males and females, and that boys and girls experience the complex differently: boys in a form of castration anxiety, girls in a form of penis envy. Penis envy is a stage in which young girls experience anxiety upon realization that they do not have a penis, beginning the transition from an attachment to the mother to competition with the mother for the affection of the father. The parallel reaction of a boy’s realization that women do not have a penis is castration anxiety, the theory that a child has a fear of damage being done to their genitalia by the parent of the same sex as punishment for sexual feelings toward the parent of the opposite sex.

Essentially, Freud provided a secular justification for the Gnostic concept of sin. According to Freud, young children are “polymorphously perverse” by nature, displaying basic sexual tendencies otherwise regarded as perverse. Societal mores “suppress” infantile “sexuality” which remains latent in the unconscious mind of adults. He further argued that as humans develop they become fixated on different and specific objects through their developmental stages from infancy through about age five. The first is the oral stage, exemplified by an infant’s incestuous “pleasure” in nursing. Next, Freud justifies coprophilia, or sexual arousal from human excrement, but he suggested that the anal stage marked by a child’s “pleasure” in evacuating his or her bowels. In the phallic stage, Freud contended, male infants become fixated on the mother as a sexual object—referred to as the Oedipus Complex—a phase brought to an end by threats of castration, resulting in the castration complex, which is the severest trauma in a young man’s life.

Freud’s theories were excessively concerned with sex and even incest, which is reflected in Sabbatean antinomianism. As Gershom Scholem noted, the Sabbateans were particularly obsessed with upturning prohibitions against sexuality, particularly those against incest, as the Torah lists thirty-six prohibitions that are punishable by “extirpation of the soul,” half of them against incest. Baruchiah Russo (Osman Baba), who in about the year 1700 was the leader of the most radical wing of the Sabbateans in Salonika and who directly influenced Jacob Frank, not only declared these prohibitions abrogated but went so far as to transform their contents into commandments of the new “Messianic Torah.” Orgiastic rituals were preserved for a long time among Sabbatean groups and among the Dönmeh until about 1900. As late as the seventeenth century a festival was introduced called Purim, celebrated at the beginning of spring, which reached its climax in the “extinguishing of the lights” and in an orgiastic exchange of wives.[59]

As Bakan indicated, in his book Moses and Monotheism, Freud makes clear that, as in the case of the Pharaohs of Egypt, incest confers god-like status on its perpetrators. In the same book, Freud argued that Moses had been a priest of Aten instituted by Akhenaten, the Pharaoh revered by Rosicrucian tradition, after whose death Moses was forced to leave Egypt with his followers. Freud also claims that Moses was an Egyptian, in an attempt to discredit the origin of the Law conferred by him. Commenting on these passages, Bakan claims that his attack on Moses was an attempt to abolish the law in the same way that Sabbatai Zevi did.

Thus, Freud disguised a Frankist creed with psychological jargon, proposing that conventional morality is an unnatural repression of the sexual urges imposed during childhood. Freud instead posited that we are driven by subconscious impulses, primarily the sex drive. In Totem and Taboo, published in 1913, which caused quite a scandal. Freud theorized about incest through the Greek myth of Oedipus, in which Oedipus unknowingly killed his father and married his mother, and incest and reincarnation rituals practiced in ancient Egypt. He used the Oedipus conflict to point out how much he believed that people desire incest and must repress that desire.

Archetypes

Freud met William James once in 1909, at a gathering of psychologists at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, who had come to hear his Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. Several other psychologists who had also attended soon came to achieve renown in their own right, including Alfred Adler, Ernest Jones, and Carl Jung (1875 – 1961), the founder analytical psychology. Jung, who had worked with Freud, commented approvingly on the Jewish mystical origins of Freudian psychoanalysis, stating that in order to comprehend the origin of Freud’s theories:

…one would have to take a deep plunge into the history of the Jewish mind. This would carry us beyond Jewish Orthodoxy into the subterranean workings of Hasidism...and then into the intricacies of the Kabbalah, which still remains unexplored psychologically.[60]

The uncle to Jung’s grandfather was Johann Sigmund Jung (1745 – 1824), a member of the Illuminati.[61] In his autobiography, Jung attributes the roots of his destiny as the founder of analytical psychology to his ancestor Dr. Carl Jung of Mainz (d. 1645), whom he portrays as a follower of the Rosicrucian and alchemist Michael Maier.[62] Jung indicated that his own grandfather, Carl Gustav Jung Sr., famous as a doctor in Basel, rector of the University and a Grand Master of Swiss Masons, and that his coat of arms included Rosicrucian and Masonic symbolism. During his student days, he entertained acquaintances with the family legend that his paternal grandfather was the illegitimate son of Goethe and his German great-grandmother, Sophie Ziegler.[63]

Jung’s mother, Emilie Preiswerk, was the youngest child of a distinguished Basel churchman and academic, Samuel Preiswerk (1799 – 1871), an antistes of the Swiss Reformed Church and a proto-Zionist, who taught Jung’s father Paul Hebrew at Basel University. Emilie’s father, who learned Hebrew because he believed it was spoken in heaven, accepted the reality of spirits, and kept a chair in his study for the ghost of his deceased first wife, who often came to visit him. Emilie herself often demonstrated “mediumistic powers” in her late teens and continued to enter curious trance states throughout her life, and during them she would communicate with the spirits of the dead.[64] In the doctoral thesis that emerged from these proceedings, On the Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena, Jung described séances held with his cousin Helene Preiswerk, whom Jung refers to her as a “young woman with marked mediumistic faculties,” and other family members.

The Psychiatrische Universitätsklinik Zürich (Psychiatric University Hospital Zürich), also called Burghölzli, is a leading psychiatric hospital in Switzerland associated with the University of Zürich.

Eugen Bleuler (1857 – 1939)

In 1900, Jung moved to Zürich and began working at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital under Eugen Bleuler (1857 – 1939), a Swiss psychiatrist and eugenicist, whose thought was derived from Spinoza and Nietzsche. Bleuler was already in communication with Freud, who eventually developed a close friendship with Jung. For six years they cooperated in their work. As sitters in Schrenck-Notzing psychical research seances, Bleuler and Jung confirmed reports of movements of objects and other phenomena previously observed with Willi Schneider’s brother Rudi and his predecessors. Records of the sittings with Rudi were compiled by Gerda Walther after Schrenck-Notzing’s death and published, with a foreword by Bleuler, by his widow.[65]

Among the formative influences on Jung were writings of Blavatsky’s secretary, G.R.S. Mead, on Gnosticism, Hermeticism, and Mithraism. Jung had an apparent interest in the paranormal and occult. For decades he attended séances and claimed to have witnessed “parapsychic phenomena.”[66] Initially, he attributed these to psychological causes, even delivering a 1919 lecture in England for the SPR on “The Psychological Foundations for the belief in spirits.” However, he began to “doubt whether an exclusively psychological approach can do justice to the phenomena in question,” and stated that “the spirit hypothesis yields better results.”[67]

Jung had read Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams shortly after its publication in 1900 and the two entered into a correspondence that was to last for over six years. In 1909, they traveled to the United States to participate in the twentieth anniversary commemoration at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, at the invitation of American psychologist, G. Stanley Hall. Jung became part of a weekly discussion group that met at Freud's house and included, among others, Alfred Adler and Otto Rank. This group evolved into the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, and Jung became its first president in 1911. Jung had begun to develop concepts about psychoanalysis and the nature of the unconscious that differed from those of Freud, however, especially Freud’s insistence on the sexual basis of neurosis. After the publication of Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious in 1912, the disagreement between the two men grew, and their relationship ended in 1914.

Jung’s early published studies on schizophrenia established his reputation, and he also won recognition for developing a word association test. Jung’s discovery of the collective unconscious and the function of archetypes arose from his own dreams and visions, but more importantly from the investigation of the fantasies of his schizophrenic patients. It was not until 1919 that he first used the term “archetypes” in an essay titled “Instinct and the Unconscious.” In addition to being a practicing psychiatrist, Jung conducted an extensive study of religious and mythological symbology that led him to develop this theory of the archetypes. Jung noticed that many religions shared similar patterns, themes, and symbols. What further provoked Jung’s curiosity was that some of these same themes and symbols arose in the dreams and fantasies of patients who suffered from schizophrenia. Jung proposed that the human mind, or psyche, is not exclusively the product of personal experience, but rather contains elements which are pre-personal, or transpersonal, that are common to all. These elements he called the archetypes and he proposed that it is their influence on human thought and behavior that gives rise to the similarities between the various myths and religions.[68]

Artwork from Jung’s Red Book: Red Cross, Serpent and Tree, and Philemon.

In 1913, at the age of thirty-eight, Jung had experienced a horrible “confrontation with the unconscious,” and worried at times that he was “menaced by a psychosis” or was “doing a schizophrenia.”[69] Jung repeatedly induced trance states in himself using methods he had learned from his experience with spiritualism, when he saw visions and heard voices. Jung began to transcribe his notes into what came to be called the Red Book, in which he described that he was visited by two figures, an old man and a young woman, who identified themselves as Elijah and Salome, and were accompanied by a large black snake. It is from his discussions with the Elijah figure—whom Jung called Philemon, as recounted in Memories, Dreams and Reflections—that Jung received his most profound insights about the nature of the human psyche. Salome, who was identified by Jung as an anima figure, began worshipping Jung, saying to him, “You are Christ.” Then the snake coiled itself around Jung, and he realized as he struggled that he had assumed the attitude of the crucifixion.

During the period when Jung began composing his Red Book, his lover Toni Wolff was a crucial figure in his life. Wolff published little under her own name, but helped Jung develop some of his best-known concepts, including anima, animus, and persona, as well as the theory of the psychological types. Her best-known paper is an essay on four “types” or aspects of the feminine psyche: the Amazon, the Mother, the Hetaira, and the Medial (or mediumistic) Woman.[70] Jung and Wolff believed they had founded a new religion, conceived through polygamy, which was reminiscent of Sabbatean antinomianism. According to Noll: “They believed in a new faith in which their former sins and evils became necessary for spiritual rebirth. God—no longer One—would emerge from individual visionary experiences and automatic writing as a multitude of natural forces or entities that were both good and evil.”[71]

Monte Verità

Monte Verità (literally Hill of Truth) in Ascona, Switzerland.

Carl Jung was a friend of Dr. Otto Gross who was a student of Freud. Gross was the dominant influence in the area of Ascona, Switzerland, originally a resort area for members of Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophy cult. In 1889, OTO founder and List Society member Franz Hartmann established, together with Alfredo Pioda and Countess Constance Wachtmeister, the close friend of Blavatsky, a theosophical monastery at Ascona. There, Hartmann published his periodical Lotusblüten (“Lotus Blossoms”), which was the first German publication to use the theosophical swastika on its cover. In 1900, Henri Oedenkoven and Ida Hofmann founded Monte Verità (The Mountain of Truth), a utopian commune near Ascona, which became a sort of early New Age haven of bohemianism and the occult, featuring experimentation in surrealism, paganism, feminism, pacifism, nudism, psychoanalysis and alternative healing.

Emil Kraepelin at one time hired Otto Gross as his assistant, but later fired him for erratic behavior and drug abuse.[72] As a bohemian drug user from youth, as well as an advocate of free love, Gross is sometimes credited as a founding father of twentieth century counterculture. While working as a ship’s doctor in 1900, he became addicted to cocaine, and remained an addict for the rest of his life. He entered a clinic for it several times but did not succeed in becoming clean. Gross was involved in a number of scandalous affairs and illegitimate children. He had an affair with Frieda Weekly, who later eloped with D.H. Lawrence, with whom she would spend the rest of her life.[73]

Years later, Jung recalled that Gross “mainly hung out with artists, writers, political dreamers, and degenerates of any description, and in the swamps of Ascona he celebrated miserable and cruel orgies.”[74] Carl Jung was highly influenced by Gross, and claimed his entire worldview changed when he attempted to analyze Gross and partially had the tables turned on him.[75] It was as a doctor that Jung met Gross, when Freud sent him to the Burghölzli, after his father asked him to cure Gross of his addictions. Freud told Jung, “You really are the only one capable of making an original contribution; except perhaps for O. Gross, but unfortunately his health is poor.”[76] Jung credited Gross with having described two general types, “inferiority with shallow consciousness” and “inferiority with contracted consciousness,” that very closely resembled what Jung described as the extraverted feeling and introverted thinking types a decade later. Gross introduced Jung to the ideas he absorbed among the sun worshippers on Monte Verità, among them paganism and the notion of an ancient matriarchal society.[77] About his relationship with Gross, Jung wrote to Freud that “I have learnt an unspeakable amount of marital wisdom, for until now I had a totally inadequate idea of my polygamous components despite all self-analysis.”[78]

Trailer for A Dangerous Method directed by David Cronenberg, featuring Vincent Cassel (right) as Otto Gross

As a psychoanalyst, Gross was one of Freud’s first disciples, but they had a falling out at the first formal psychoanalysis convention, when Gross wanted to draw radical political conclusions from Freud’s theories. Gross was described by Freud’s English disciple, Ernest Jones, as:

…the nearest approach to the romantic ideal of a genius I have ever met, and he also illustrated the supposed resemblance of genius to madness, for he was suffering from an unmistakeable form of insanity that before my very eyes culminated in murder, asylum and suicide.[79]

As noted by Elizabeth Wilson in Bohemians, madness was quite prevalent among bohemians, and Gross “and his fellow Nietzscheans blurred the distinction between madman and seer. Nietzsche himself had gone mad, and Gross was the hero of a youth movement for whose adherents madness was a privileged condition and the psychiatric asylum an instrument of patriarchal state oppression.”[80] Based on his interpretation of Nietzsche and Freud, Gross’ aim was to revive the cult of Astarte to bring about a “sexual utopia” through “sexual revolution and orgy.”[81] Gross’ motto, taken from Nietzsche, was “repress nothing.” Based on his interpretation of Nietzsche and Freud, Gross’ aim was to revive the cult of the pagan goddess to bring about a “sexual utopia” through “sexual revolution and orgy.”[82] Jung wrote Freud, “Dr. Gross tells me he puts a quick stop to the transference by turning people into sexual immoralists. He says the transference to the analyst and its persistent fixation are more monogamy symbols and as such symptomatic of repression. The truly healthy state for the neurotic is sexual immorality. Hence he associates you with Nietzsche.”[83]

Bloomsbury Group

Bertrand Russell, John Maynard Keynes and Lytton Strachey, all member of the Cambridge Apostles

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809 – 1892)

Freud provided the foundation for the reinterpretation of “Victorian” morality which became the basis of the “bohemianism” cultivated by the Bloomsbury Group of which D.H. Lawrence was a member. The leading Fabians intersected with the Bloomsbury Group, a group of writers and intellectuals who were particularly influential in England, who revolted against a “Victorian morality” which was shaped by their ancestors, the Clapham Sect.[84] Leonard, the son of Sidney Woolf, a Jewish barrister and Queen’s Counsel, and his wife Virginia Woolf formed the core of the Bloomsbury Group, along with the well-known economist John Maynard Keynes and his homosexual lover, Ludwig Wittgenstein, E.M. Forster, Roger Fry, Lytton Strachey and Bertrand Russell.

The Bloomsbury Set was also closely affiliated with the Cambridge Apostles—an intellectual secret society at Cambridge University, founded in 1820—who were predominantly homosexuals, inspired by their interest in “Platonic love.” The Apostles included a long list of the most eminent Victorians. To name a few: Charles Darwin’s brother Erasmus, poets Arthur Hallam and Alfred Tennyson, Henry Sidgwick and his brother-in-law Lord Balfour. Of the Bloomsbury Set, John Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey and his brother James, E.M. Forster and Rupert Brooke were all Apostles. Through the Apostles they also encountered the analytic philosophers G.E. Moore and Bertrand Russell.

Left to right: Lady Ottoline Morrell, Maria Nys (neither members of Bloomsbury), Lytton Strachey, Duncan Grant, and Vanessa Bell.

Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941)

From 1910, core members of the group became psychoanalysts. In 1917, Leonard and Virginia Woolf founded the Hogarth Press, which became the official psychoanalytic publishing house, publishing numerous books by Freud and members of the Bloomsbury group. As well as publishing the works of the members of the Bloomsbury group, the Hogarth Press was at the forefront of publishing works on psychoanalysis and translations of foreign, especially Russian, works. There is evidence suggesting that Leonard Woolf and fellow Bloomsbury members John Maynard Keynes and Lytton Strachey became sufficiently interested to make significant use of psychoanalysis in their own work.[85] As explained by Ted Wilson in Bloomsbury, Freud, and the Vulgar Passions, according to Leonard Woolf, opposition to civilized values in European history can be traced to “the sense of sin,” which he claimed “accounts for the rigidity and persistence of the authoritarian view of politics.”[86] According to Woolf, Freud’s contributions to an understanding of the conscious and unconscious mind were as important as those of Newton and Darwin to other sciences:

And just as Newton’s and Darwin’s discoveries or hypotheses profoundly affected spheres of thought and knowledge far outside the sciences in which they were made, so Freud’s discoveries regarding the unconscious are of immense significance, not merely for individual psychology, but also for religion, ethics, politics, and sociology. Of all his contributions, that which is probably the most fundamental and far-reaching concerns man’s sense of sin.[87]

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes (1883 – 1946)

Influenced by the crypto-Sabbatean antinomianism of Freud, the Bloomsbury Group attempted to push the bounds of sexual morality and public decency, under the guise of challenging society’s prudishness. The Bloomsbury Group, which reacted against the social norms, “the bourgeois habits ... the conventions of Victorian life,” deeply influenced literature, aesthetics, criticism, and economics as well as modern attitudes towards feminism, pacifism, and sexuality.[88] The group “believed in pleasure... They tried to get the maximum of pleasure out of their personal relations. If this meant triangles or more complicated geometric figures, well then, one accepted that too.”[89] According to John Maynard Keynes:

We repudiated entirely customary morals, conventions and traditional wisdom. We were, that is to say, in the strict sense of the term, immoralists. The consequences of being found out had, of course, to be considered for what they were worth. But we recognized no moral obligation on us, no inner sanction, to conform or to obey. Before heaven we claimed to be our own judge in our own case.

Aldous Huxley and D.H. Lawrence (1885 – 1930), author of Lady Chatterley’s Lover

For example, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, first published in 1928, soon became notorious for its explicit descriptions of sex, and its use of then-unprintable words. Likewise, E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, which took place in the caves of Malabar, explored notions of “suppressed” sexuality. As the Bloomsbury group encouraged a liberal approach to sexuality, in 1922 Virginia Woolf met the wife of Harold Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West, with whom she had a sexual affair. Agreeing to an open marriage, both Sackville-West and her husband had same-sex relationships, as did some of the people in the Bloomsbury Group. Tragically, however, modern scholars, including her nephew and biographer, Quentin Bell, have suggested the symptoms of mental illness she suffered from were influenced by the sexual abuse to which she and her sister were subjected by their half-brothers George and Gerald Duckworth, which Woolf recalls in her autobiographical essays. Until her suicide in 1941, Woolf was afflicted with manic depression or bipolar disorder as well as auditory hallucinations.[90]

World League for Sexual Reform

Edith Lees and Havelock Ellis (1859 – 1939), who maintained an “open marriage.”

As Heather Wolffram has shown, early-twentieth-century German psychical research was heavily dominated by studies in physical mediumship through the influence of the pioneering work in hypnotism and sexology of Albert von Schrenck-Notzing.[91] In 1899, at the First International Congress of Hypnotism, Schrenck-Notzing declared that he had cured a man of his homosexuality. Through hypnosis, he claimed, he had manipulated the man’s sexual impulses, diverting them from his interest in men to a lasting desire for women.[92] According to Frederick Crews in Freud: The Making of an Illusion:

More generally, the quarter century after 1880 was the golden age of sexology, whose major figures—Richard von Krafft-Ebin, Albert Moll, Iran Bloch, Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, and Havelock Ellis— exerted a decisive and multifarious influence on Freud. There is no sexual topic in his writings, from homosexuality, bisexuality, sadomasochism, and fetishism through infantile masturbation, the pregenital “component instincts,” they psychosexual stages, and even the evolutionary origin of sexual disgust, that wasn’t anticipated and largely shaped by his readings.[93]

British physician Havelock Ellis (1859 – 1939) was a contributor to Alfred P. Orage’s New Age magazine. Ellis joined The Fellowship of the New Life in 1883, meeting other social reformers like Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor, Edward Carpenter, George Bernard Shaw and Annie Besant. Ellis served as president of the Galton Institute and supported eugenics. He served as vice-president to the Eugenics Education Society and wrote:

Eventually, it seems evident, a general system, whether private or public, whereby all personal facts, biological and mental, normal and morbid, are duly and systematically registered, must become inevitable if we are to have a real guide as to those persons who are most fit, or most unfit to carry on the race.[94]

Margaret Sanger (1879 – 1966), founder of Planned Parenthood, who reportedly had an affair with Havelock Ellis

Ellis is considered the founding father of sexology, and to have challenged the sexual “taboos” of his era regarding masturbation and homosexuality and supposedly revolutionized the conception of sex in his time. Ellis also developed psychological concepts such as autoerotism and narcissism, later developed further by Sigmund Freud. The 1897 English translation of Ellis’ book Sexual Inversion, was the first English medical textbook on homosexuality, describing the sexual relations of homosexual males, including men with boys. Ellis married the English writer and proponent of women’s rights, Edith Lees. From the beginning, their marriage was unconventional, as Edith was openly lesbian. Their “open marriage” was the central subject in Ellis’ autobiography My Life. Ellis reportedly had an affair with Margaret Sanger, the founder of the American Birth Control League, which later became the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Eugenicist Auguste-Henri Forel (1848 – 1931)

Many Fabians were involved in the World League for Sexual Reform, a league for coordinating policy reforms related to greater openness around sex. Congress speakers included prominent Fabians like Norman Haire, George Bernard Shaw and Bertrand Russell. Although not a speaker, Albert Einstein was in contact with the Congress. Havelock Ellis and the eugenicist Auguste Forel (1848 – 1931), was one the League's presidents. the World League for Sexual Reform. Forel was a Swiss psychiatrist notable for his investigations into the structure of the human brain and that of ants. His first major work was a 450 page treatise on the ants of Switzerland which was published in 1874 and commended by Charles Darwin.

A party at the Institute for Sexual Science. Magnus Hirschfeld (1868 – 1935) is second from right

Harry Benjamin (1885 – 1986) sexologist widely known for his clinical work with transsexualism.

The league was formed in 1921, when Magnus Hirschfeld (1868 – 1935) organized the First Congress for Sexual Reform. Hirschfeld, a prominent Jewish homosexual, founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee (SHC), which historian Dustin Goltz characterized as having carried out “the first advocacy for homosexual and transgender rights.”[95] Hirschfeld coined the term “transvestite.” Under Hirschfeld’s leadership, the SHC gathered over 5000 signatures from prominent Germans on a petition to overturn Paragraph 175 of the German legal code, which criminalized homosexuality. Signatories included Albert Einstein, Hermann Hesse, Käthe Kollwitz, Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, August Bebel, Max Brod, Karl Kautsky, Stefan Zweig, Gerhart Hauptmann, Martin Buber, Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Eduard Bernstein.

Hirschfeld was friends with Dr. Harry Benjamin (1885 – 1986), the sex-change-operation pioneer. Benjamin recounted that he met Magnus Hirschfeld through a girlfriend, who knew the police official in charge investigating of sexual offenses. They repeatedly visited the homosexual bars in Berlin. Benjamin especially remember the “Eldorado” with its drag shows, and where many of the customers dressed in the clothing of the other sex. The word “transvestite,” which had not yet been invented, was coined by Hirschfeld only in 1910 in his well-known study.[96]

Eugen Steinach (1861 – 1944) conducted sex change operations in guinea pigs

Benjamin was also in contact with Eugen Steinach (1861 – 1944), an Austrian physiologist and pioneer in endocrinology. Steinach was known to have successfully performed sex change operations in rats and guinea pigs by means of castration and transplantation of endocrine glands. He developed the “Steinach operation,” or “Steinach vasoligature,” the goals of which were to reduce fatigue and the consequences of aging and to increase overall vigor and sexual potency in men. It consisted of a half-(unilateral) vasectomy, which Steinach theorized would shift the balance from sperm production toward increased hormone production in the affected testicle.[97] Steinach introduced Benjamin to Freud, who admitted to him to having undergone the operation. Freud believed that it had done him good, that his vitality had been strengthened, but he asked Benjamin not to tell anyone about his operation until after his death.[98]

lbert Moll (1862 – 1939)

Benjamin also knew Margaret Sanger quite well and also Ben Lindsey and many other Americans who have worked for the alleviation of sexual misery. In 1926, Benjamin spoke at the great International Congress for Sex Research organized by Albert Moll (1862 – 1939), who along with Hirschfeld is considered the founder of sexology. Moll, an active promoter of hypnotism in Germany, went to Nancy and studied with Hippolyte Bernheim.[99] Moll believed sexual nature involved two entirely distinct parts: sexual stimulation and sexual attraction. In an article of 1894, Max Dessoir published an account of the evolution of the sex instinct from undifferentiated to differentiated, which was taken up by Albert Moll and Sigmund Freud. Freud cites it approvingly in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.[100] Moll published his account of the history of hypnotism and his own experiments in Hypnotism (1889), in preparation of which he was assisted by support from Prof. Auguste Forel and Max Dessoir. In his book Christian Science, Medicine, and Occultism (1902), Moll criticized practices such as Christian Science, spiritualism and occultism and wrote they were the result of fraud and hypnotic suggestion. He wrote that fraud and hypnotism could explain mediumistic phenomena. Shortly after the death of Albert von Schrenck-Notzing in 1929, Moll published a treatise on the psychology and pathology of parapsychologists, with Schrenck-Notzing serving as a prototype of a scientist suffering from an “occult complex.” Moll’s analysis concluded that parapsychologists vouching for the reality of supernormal phenomena, such as telepathy, clairvoyance, telekinesis and materializations, suffered from a morbid will to believe, which paralyzed their critical faculties and made them cover obvious mediumistic fraud.[101]

[1] Karl Pearson. The Life, Letters, and Labours of Francis Galton (University Press, London, 1914).

[2] David Rivera. Final Warning, Chapter 5.1: “The Fabians, the Round Table, and the Rhodes Scholars.”

[3] Edward R. Pease. The History of the Fabian Society (Library of Alexandria, 1925).

[4] Dinnage Rosemary. Alone! alone!: lives of some outsider women (New York: New York Review Books, 2004).

[5] Bal Ram Nanda. The Nehrus (Oxford University Press, 1962). p. 65.

[6] Om Prakash Misra. Economic Thought of Gandhi and Nehru: A Comparative Analysis (M.D. Publications. 1995). pp. 49–65.

[7] Cited in Edward Alexander. Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin, and the Modern Temper (Ohio State University Press, 1973), p. 190.

[8] Philipe Thody. Huxley: A Biographical Introduction (Scribner, 1973).

[9] Jonathan Freedland. “Eugenics: the skeleton that rattles loudest in the left’s closet.” The Guardian (February 17, 2012).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Dennis Sewell. “How eugenics poisoned the welfare state.” The New Spectator (November 25, 2018).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Victoria Brignell. “The eugenics movement Britain wants to forget.” New Statesman (December 9, 2010). Retrieved from https://www.newstatesman.com/society/2010/12/british-eugenics-disabled

[14] Edwin Black. War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race (Dialog Press, 2012).

[15] Harry Bruinius. Better For All the World. The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America's Quest for Racial Purity (New York: A. A. Knopf, 2006).

[16] Theodore Roosevelt, Letter to Charles Davenport (New York, January 3, 1913).

[17] “Eugenics Record Office - Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory - Library & Archives.” library.cshl.edu. Retrieved from http://library.cshl.edu/special-collections/eugenics

[18] “Madison Grant. The Passing of the Great Race: Or, the Racial Basis of European History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922), xxxi.

[19] Stefan Kühl. Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism (Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 85.

[20] H. J. Eysenck. Encyclopedia of Psychology.

[21] The Freud/Jung Letters - The correspondence between Sigmund Freud and C. G. Jung (1906 - 1914). Bollingen Series XCIV (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1974).

[22] Andreas Sommer. “Policing Epistemic Deviance: Albert von Schrenck-Notzing and Albert Moll.” Medical History, 2012 Apr; 56(2): 255–276.

[23] Jastrow. Autobiography. in Carl Murchison [ed.] A History of Psychology in Autobiography, vol. 1 (Worcester, MA: Clark University Press, 1930), pp. 135–62, cited in Sommer. “Policing Epistemic Deviance.”

[24] Goodrick-Clarke. The Occult Roots of Nazism, p. 23.

[25] Andreas Sommer. “Normalizing the Supernormal: The Formation of the “Gesellschaft Für Psychologische Forschung” (“Society for Psychological Research”), c. 1886–1890.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 2013 January; 49(1): 18–44.

[26] Jaan Valsiner & Rene van der Veer. The Social Mind: Construction of the Idea (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 70.

[27] Andreas Sommer. “Policing epistemic deviance: Albert Von Schrenck-Notzing and Albert Moll(1).” Medical History. 56: 255–276.

[28] Colin Williamson. Hidden in Plain Sight: An Archaeology of Magic and the Cinema (Rutgers University Press, 2015), p. 203.

[29] Pascal Themanlys. “Le Mouvement Cosmique.” Retrieved from http://www.abpw.net/cosmique/theon/mouvem.htm

[30] Andreas Sommer. “Policing Epistemic Deviance: Albert von Schrenck-Notzing and Albert Moll.” Medical History, 2012 Apr; 56(2): 255–276.

[31] Kalush. The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero (Atria Books, 2006). p. 419.

[32] Harry Houdini. A Magician among the Spirits (Cambridge Library Collection - Spiritualism and Esoteric Knowledge). (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[33] M. Brady Brower. Unruly Spirits: The Science of Psychic Phenomena in Modern France (University of Illinois Press, 2010), p. 120.

[34] Andreas Sommer. “Normalizing the Supernormal: The Formation of the “Gesellschaft Für Psychologische Forschung” (“Society for Psychological Research”), c. 1886–1890.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 2013 Jan; 49(1): 18–44.

[35] Corinna Treitel. A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), p. 45.

[36] Corinna Treitel. A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), p. 46.

[37] Sommer. “Policing Epistemic Deviance.”

[38] Joseph Jastrow. The Psychology of Conviction (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1918), pp. 100–111.

[39] Sommer. “Policing Epistemic Deviance.”

[40] Sander Gilman. Multiculturalism and the Jews (Routledge, 2013), p. 73.

[41] Alan Kim. “Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 Edition).

[42] Spence. Secret Agent 666, Kindle Locations 1556-1558.

[43] C.E.M. Hansel. ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-Evaluation (Prometheus Books, 1980). pp. 58–64.

[44] Sommer. “Policing Epistemic Deviance.”

[45] Hugo Münsterberg. American Problems from the Point of View of a Psychologist (New York: Moffat, Yard, 1912).

[46] Ibid.

[47] James P. Keeley. “Subliminal Promptings: Psychoanalytic Theory and the Society for Psychical Research.” American Imago, vol. 58 no. 4, 2001, pp. 767–791.

[48] Dr. Sanford Drob. “Freud and Chasidim: Redeeming the Jewish Soul of Psychoanalysis.” The Jewish Review. Volume 3 , Issue 1 (Sept, 1989 | Tishrei, 5750).

[49] Joseph H. Berke. The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots (London: Karnac Books, 2015), p. 8.

[50] Maya Balakirsky Katz. “An Occupational Neurosis: A Psychoanalytic Case History Of a Rabbi.” AJS Review 34, no. 1 (2010).

[51] R. Gregory ed. The Oxford Companion to the Mind (1987), p. 332.

[52] Sigmund Freud. Introductory Lectures of Psychoanalysis (PFL 1) p. 501-2.

[53] Cited in Ernest Jones. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (1964) p. 211.

[54] Corinna Treitel. A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), p. 49.

[55] Marsha Aileen Hewitt. “Freud and the Psychoanalysis of Telepathy: Commentary on Claudie Massicotte’s “Psychical Transmissions”.” Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 24 (2014): 103 - 108.

[56] Sigmund Freud. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, S.E. Vol. 7, p. 187.

[57] Frederick Crews. Freud: The Making of an Illusion (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017), p. 547.

[58] Ibid., p. 516.

[59] Gershom Scholem. “Redeption Through Sin,” The Messianic Idea in Judaism: And Other Essays on Jewish Spirituality, (New York: Schocken, 1971).

[60] Carl. G. Jung. Letters (Gerhard Adler, Aniela Jaffe, and R.F.C. Hull, Eds.). (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973), Vol. 2, pp. 358–9.

[61] Terry Melanson. “Was Carl Jung’s Ancestor an Illuminatus?” Bavarian-Illuminati.com ((17/2/2009)). Retrieved from http://www.bavarian-illuminati.info/2009/02/was-carl-jungs-ancestor-an-illuminatus/

[62] Hereward Tilton. The Quest for the Phoenix: Spiritual Alchemy and Rosicrucianism in the Work of Count Michael Maier (1569-1622), (Walter de Gruyter, 2003), p. 23.

[63] Gerhard Wehr. Jung: A Biography (Boston/Shaftesbury, Dorset: Shambhala, 1987), p. 14.

[64] Gary Lachman. Jung the Mystic (Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition), p. 18.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Carl Gustav Jung (1997). “Jung on Synchronicity and the Paranormal.” Psychology Press. p. 6.

[67] Ibid., p. 7.

[68] Carl Jung – What are the Archetypes? Academy of Ideas (February 14, 2017). Retrieved from https://academyofideas.com/2017/02/carl-jung-what-are-archetypes/

[69] Sara Corbett. “The Holy Grail of the Unconscious.” The New York Times (September 16, 2009).

[70] Toni Wolff. Structural Forms of the Feminine Psyche (1956).

[71] Noll. The Aryan Christ, p. 94.

[72] Rik Loose. The Subject of Addiction: Psychoanalysis and The Administration of Enjoyment (Routledge, 2018).

[73] Cited in Gottfried Heuer. “Jung’s twin brother. Otto Gross and Carl Gustav Jung.” Journal of Analytical Psychology (2001, 46: 3), p. 670.

[74] Cited in Gottfried Heuer. “Jung’s twin brother. Otto Gross and Carl Gustav Jung.” Journal of Analytical Psychology (2001, 46: 3), p. 670.

[75] Ronald Hayman. A Life of Jung (1999), p. 102.

[76] Cited in Richard Noll. The Aryan Christ: The Secret Life of Carl Jung, (Random House, 1997), p. 71.

[77] Lachman. Jung the Mystic, p. 74

[78] Cited in Jay Sherry. Carl Jung: Avant-Garde Conservative (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), p. 41.

[79] Elizabeth Wilson. Bohemians. (London: Tauris Park Paperpacks, 2003) p. 186.

[80] Ibid. p. 199.

[81] Mary Ann Mattoon & Robert Hinshaw. Cambridge 2001: Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Congress for Analytical Psychology (Daimon, 2003) p. 127.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Brenda Maddox. Freud’s Wizard: Ernest Jones and the Transformation of Psychoanalysis (Da Capo Press, 2007) p. 54.

[84] Ronald Blythe. As cited in David Daiches (ed.), The Penguin Companion to Literature I (Penguin, 1971), p. 54

[85] Douglass W. Orr, M.D. Psychoanalysis and the Bloomsbury Group (Clemson University Digital Press, 2004).

[86] Ted Wilson. “Bloomsbury, Freud, and the Vulgar Passions.” Social Research, Vol. 57, No. 4, Reception of Psychoanalysis (WINTER 1990) p. 797.

[87] Woolf. Principia, pp. 64-65

[88] Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf (London, 1996) p. 54.

[89] C. P. Snow. Last Things (Penguin, 1974) p. 84.

[90] Susan Sellers. The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf. (Cambridge University Press, 2010) p. 31.

[91] Heather Wolffram. “Stepchildren of Science: Psychical Research and Parapsychology in Germany, c. 1870–1939.” Clio Medica vol. 88 (2009).

[92] Tommy Dickinson. ‘Curing Queers’: Mental Nurses and Their Patients, 1935-74 (Manchester University Press, 2016).

[93] Frederick Crews. Freud: The Making of an Illusion (Metropolitan Books, 2017), p. 277.

[94] Havelock Ellis. The Task of Social Hygiene.

[95] Dustin Goltz. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Movements,” In Amy Lind & Stephanie Brzuzy, (eds.). Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality: Volume 2 (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008), pp. 291 ff.

[96] “The Transatlantic Commuter.” Archiv für Sexualwissenschaft. Hu-Berlnin.de Retrieved from http://www2.hu-berlin.de/sexology/GESUND/ARCHIV/TRANS_B5.HTM

[97] “Medicine: What Am I Doing?” Time (February 12, 1940).

[98] Ibid.

[99] Henri Ellenberger. The Discovery of the Unconscious (1970) p. 88.

[100] Sigmund Freud. On Sexuality (PFL 7), p. 152-3.

[101] Sommer. “Policing Epistemic Deviance.”

Volume Three

Synarchy

Ariosophy

Zionism

Eugenics & Sexology

The Round Table

The League of Nations

avant-Garde

Black Gold

Secrets of Fatima

Polaires Brotherhood

Operation Trust

Aryan Christ

Aufbau

Brotherhood of Death

The Cliveden Set

Conservative Revolution

Eranos Conferences

Frankfurt School

Vichy Regime

Shangri-La

The Final Solution

Cold War

European Union