7. The Royal Society

The Great Instauration

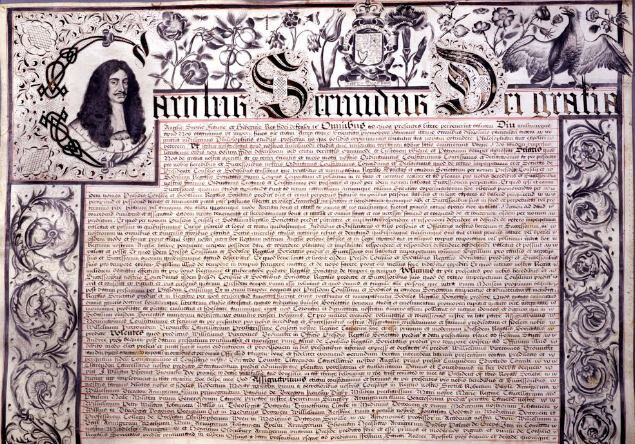

Although the movement was defeated in Germany with the start of the Thirty Years War, the Rosicrucians regrouped in England to found the Royal Society in 1660, as a revival of the Invisible College of Samuel Hartlib and his circle, coinciding with the readmittance of the Jews in England under the leadership of Menasseh ben Israel. When Oliver Cromwell died in 1658, his despotic legacy fell to his son Richard who did not possess his father’s ruthlessness, with the result that it was not long before Charles II the late king’s son was invited back to rule as King of England in 1660. After the Stuarts returned to Jerusalem (Britain) in 1660, Charles II granted his personal protection to the Jews, despite attempts by various Puritans to persecute or exploit them.[1] He also responded positively to the plan of Sir Robert Moray, one of the founders of modern Freemasonry in Great Britain, to establish the Royal Society of Sciences as a Solomonic organization for the non-sectarian, universalist exploration of the natural and supernatural sciences.[2] In the Charter, the Charles II indicated his desire and favor to expand all forms of learning to all corners of “the Empire,” with a special emphasis on “natural philosophy” or what only later became “science.” Comenius, a core member of the Hartlib Circle, dedicated his book, The Way of Light, published in Amsterdam in 1668, to the Royal Society—which he recognized as the fruition of his and his friends efforts—addressing its Fellows as “illuminati.”[3] As early as 1638, a hint as to a connection between Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry was published, with the earliest known reference to the “Mason Word,” in a poem at Edinburgh in 1638:

For what we do presage is not in grosse,

For we be brethren of the Rosie Crosse:

We have the Mason word and second sight,

Things for to come we can foretell aright…[4]

Henry Oldenburg (c. 1619 – 1677), original member of the Invisible College and first secretary of the Royal Society

It was through its promotion of the “Great Instauration” initiated by Francis Bacon, that the Royal Society provided the philosophical underpinnings of the Scientific Revolution, which marked the emergence of modern science in Europe towards the end of the Renaissance and continued through the late eighteenth century, influencing the Enlightenment. The publication in 1543 of Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is often cited as marking the beginning of the Scientific Revolution. Its beginning is generally considered to have ended in 1632 with publication of Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, dedicated to his patron, Ferdinando II de’ Medici. The completion of the Scientific Revolution is attributed to the “grand synthesis” of Royal Society member Isaac Newton’s Principia (1687), which formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation, thereby completing the synthesis of a new cosmology.

The expression “knowledge is power” is commonly attributed Bacon, occurring as scientia potestas est (“knowledge itself is power”) in his Meditationes Sacrae (1597). Paradoxically, the Scientific Revolution begins with the study of magic as “natural philosophy” initiated by Bacon, who was believed to represent the advent of Elias Artista. “This transformation of both Elias and Elisha from prophets into magi and natural philosophers,” observed Allison P. Coudert, “reveals the way apocalyptic and messianic thought contributed to the emerging idea of scientific progress.”[5] As explained by Herbert Breger, in “Elias artista - a Precursor of the Messiah in Natural Science”:

A common association in the 19th century and one which has persisted into the 20th century, was to link the development of natural science with the improvement of the human condition. Thus, it would appear that the figure of Elias artist a was a forerunner of the liberal definition of progress in natural science: scientific advancement as vehicle of social advancement, individual well-being and as a means of attaining a more humane society.[6]

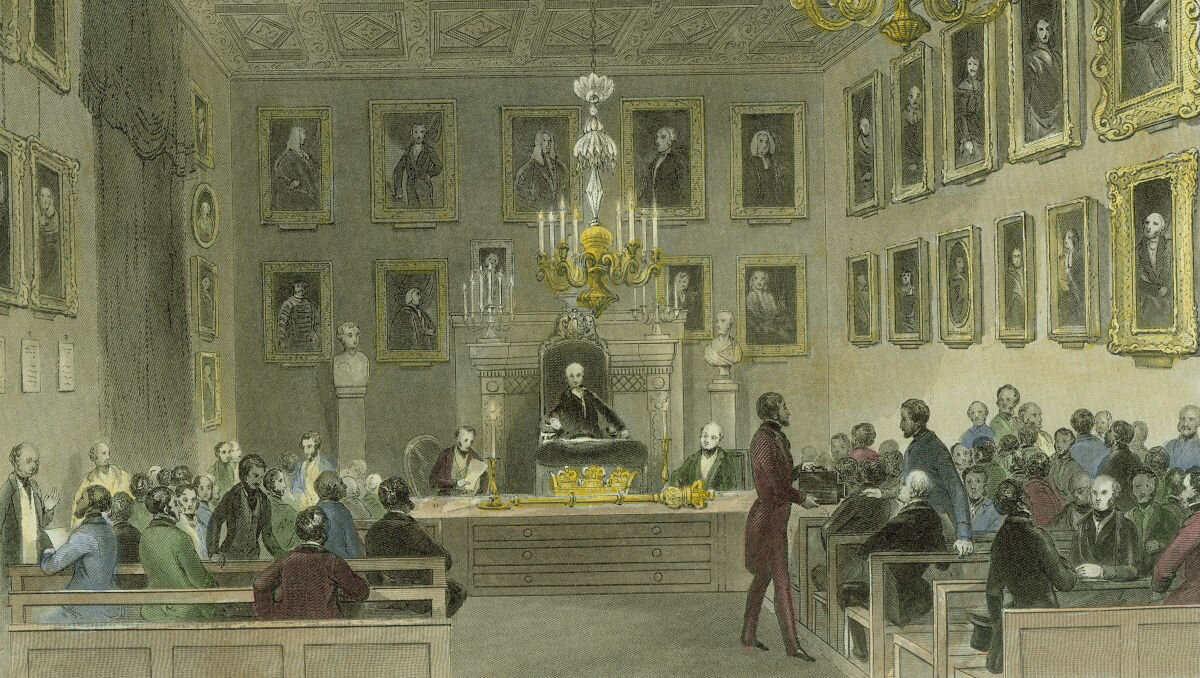

The frontispiece of Thomas Sprat's History of the Royal Society (1667), with Lord Brouncker, the society's first president, seated to the left of the bust of King Charles II, and Sir Francis Bacon to the right, the “artium instaurator” (Arts Restorer)

In 1618, Bacon had decided to secure a lease for York House, where he would host banquets that were attended by the leading men of the time, including poets, scholars, authors, scientists, lawyers, diplomats, and foreign dignitaries On January 22, 1621, in honor of his sixtieth birthday, a select group of men assembled in the large banquet hall at Bacon’s York House for what has been described as a Masonic banquet.[7] Only those of the Rosicrosse (Rosicrucians) and the Masons who were already aware of Bacon’s leadership role were invited.[8] On that day, a long-time friend of Bacon, the poet Ben Jonson, best known for his satirical plays, Volpone, The Alchemist, and Bartholomew Fair, gave a Masonic ode to Bacon.

According to Burton, Elias Artista was considered by some to be a person who was alive at that time, and using language that clearly applied to Francis Bacon, he referred to him as “the renewer of all arts and sciences,” “reformer of the world,” “a most divine man,” and the “quintessence of wisdom.”[9] Bacon’s agenda, outlined in his Advancement of Learning, was to transform society by supplanting organized religion in favor of occultism. Bacon prescribed the study of “natural philosophy,”—which would become the origin of modern science—a branch of magic that sought to study the universe in order to discover, and later manipulate, its occult properties. In The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science, John Henry remarked that, “a number of historians of science have refused to accept that something which they see as so irrational could have had any impact whatsoever upon the supremely rational pursuit of science. Their arguments seem to be based on mere prejudice, or on a failure to understand the richness and complexity of the magical tradition.”[10]

The Royal Society were influenced by the “new science,” as promoted by Francis Bacon in his New Atlantis, from approximately 1645 onwards.[11] Although Bacon is considered one of the fathers of modern science, in Francis Bacon: From Magic to Science, Paolo Rossi showed that Bacon’s projected reform was tinged with a millennial aspect, and drawn from the Hermetic tradition of the “Magia and Cabala” of the Renaissance. Frances Yates observed a link between Bacon’s Great Instauration and the ideals as expressed in the Rosicrucian manifestos, for the two were calling for a reformation of both “divine and human understanding,” and both held a view of the purpose of mankind to return to the “state before the Fall.”[12] Bacon had proposed a great reformation of all process of knowledge for the advancement of learning divine and human, which he called Instauratio Magna (“The Great Instauration”). Bacon planned his instauration in imitation of the Divine Work: the Work of the Six Days of Creation, as defined in the Bible, leading to the Seventh Day of Rest or Sabbath in which Adam’s dominion over creation would be restored. When this salvation through science is achieved the millennium will be at hand.[13]

As the notorious Baconian scholar William Francis C. Wigston shows, Bacon also makes reference to the great conjunction of 1603/04 in the margin to his early pseudonymous text on scientific reform, Valerio Terminus Interpretation of Nature: with the annotations of Hermes Stella (1603). Thomas Vaughan (1621 – 1666), who published in 1652 an English version of the Fama and Confessio of the Rosicrucians, declared Elias Artista to have already been born into the world and that “the entire Universe is to be transmuted and transfigured by the science of this Artist into the pure mystical gold of the Spiritual City of God, when all currencies have been destroyed.”[14]

Bacon referred to himself as buccinator novi temporis (“herald of a new time”),[15] and recalled the prophecy of Daniel, that “Many shall go to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased,” ushered in by the “last ages” when “the thorough passage of the world and the advancement of the sciences are destined by fate, that is, by Divine Providence, to meet in the same age.”[16] The prophetic quote from Daniel is prominently displayed in Latin as “Multi pertransibunt et augebitur scientia” on the title page of Bacon’s 1620 Instauratio Magna, which also serves as the illustrated title page to Novum Organum, and the 1640 Advancement and of Learning.

Susana Åkerman remarked, “As the French historian Gabriel Naudé argued in 1623, it would not even be entirely wrong to call this understanding Postellian, for Postel baptized his own program of mystical reform the Instauration of the new age.”[17] Bacon stated that “Salomon is said to have written a natural history of all that is green from cedar to the moss (which is but a rudiment between putrefaction and a herb) and also of all that liveth and moveth.”[18] The phrase that Bacon then used, and which he repeated in all his writings on the scientific method, “Nay, the same Salomon the king affirmeth directly that the glory of God is to conceal a thing, but the glory of a King is to find it out,” is the concluding line of Guillaume de Postel’s Candelabri typicy (1547).[19] Bacon cited Postel as a man who “in our time, lived nearly 120 years; the top of his moustache being still black, and not at all grey. He was a man of disordered brain and unsound mind, a great traveler and mathematician and somewhat tainted with heresy.”[20]

According to Bacon, “The aim of magic is to recall natural philosophy from the vanity speculations to the importance of experiments.”[21] As Bacon clarifies:

We here understand magic in its ancient and honourable sense—among the Persians it stood for a sublimer wisdom, or a knowledge of the relations of universal nature, as may be observed in the title of those kinds who came from the East to adore Christ. And in the same sense we would have it signify that science, which leads to the knowledge of hidden forms, for producing great effects, and by joining agents to patients setting the capital works of nature to view.[22]

Joseph Agassi writes: “Historians who write on Bacon’s Utopian college view it as an inspiration for the early Royal Society.”[23] During the Restoration of Charles II, Bacon became the popular inspiration for “science,” from the Latin Scientia, first entered public use. In the fourteenth century the term in English referred to knowledge gained through experiment, systematic observation and reasoning. This restricted modern sense of term in the seventeenth century was termed natural philosophy. It was subsequent to the founding of the Royal Society that the word took on a consistent modern association with the Baconian method.[24]

Rabbi Templo

The chief rabbi of Hamburg in 1628, Jacob Judah Leon (1602-1675)—known as Leon Templo—with the assistance of the Christian theologian Adam Boreel, who was associated with the Hartlib Circle

Charles I of England, son of King James, with his wife Henrietta Maria, daughter of Marie de Medici, with their children, the future Charles II of England and Princess Mary.

In 1649, after the execution of Charles I and the establishment of the Cromwellian Commonwealth, his exiled son Charles II was initiated into Freemasonry.[25] As “Mason Kings,” explains Schuchard, James and his son Charles I and grandson Charles II, considered themselves Solomonic monarchs and employed Jewish visionary and ritual themes while they sought to rebuild the “Temple of Wisdom” in their kingdoms.[26] Referring to Charles I’s expertise in numerical-linguistic combinations and invisible inks, John Milton denounced his royalist correspondents as “a Sect of those Cabalists,” who deserved exposure and punishment.[27] In 1665, the identification of Stuart Masons with Jews was expressed in a rare manuscript, “Ye History of Masonry,” written by Thomas Treloar.[28] Using Hebrew lettering and symbols, Treloar wrote a highly Judaized version of the Old Charges of operative Masonry, in which Solomon and Hiram play much greater roles than in earlier English texts. He drew on earlier Scottish traditions of Hiram, the murdered architect who could be rejuvenated by certain Kabbalistic and necromantic rituals.[29] Treloar portrayed Charles II as the restored and anointed king who now reigned over “the Craft.”[30]

Charles II’s mother, Queen Henrietta Maria, was the daughter of Henry IV of France and Marie de Medici. Her brother was Louis XIII of France, who married Anne of Austria, the daughter of Philip III of Spain, Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece, and fathered of Louis XIV, the “Sun King.” Henrietta Maria’s sister, Christine Marie, married Victor Amadeus I of Savoy, the son of Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy, whose birth was prophesied by Nostradamus, and who was also titular King of Cyprus and Jerusalem.[31] Charles Emmanuel I was also the grandson of Francis I of France, a supporter of Guillaume Postel and Leonardo da Vinci. Christine Marie also rebuilt Palazzo Madama in Turin following the advice of master alchemists.[32]

Genealogy of Charles II of England

FREDERICK II OF DENMARK (Order of the Garter; close friend of AUGUSTUS, ELECTOR OF SAXONY; interested in alchemy and astrology; supported TYCHO BRAHE) + Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow

Elizabeth of Denmark + Henry Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Anne of Denmark + KING JAMES I OF ENGLAND

Elizabeth Stuart + ALCHEMICAL WEDDING: Frederick V of the Palatinate

CHARLES I OF ENGLAND + Henrietta Maria (daughter of Henry IV of France and Marie de Medici)

CHARLES II OF ENGLAND + Catherine of Braganza (daughter of John IV of Portugal + Luisa de Guzmán, from the ducal house of Medina-Sidonia of allegedly crypto-Jewish background. See Genealogy of the Order of Santiago)

Mary, Princess of Orange + WILLIAM II, PRINCE OF ORANGE (grandson of WILLIAM THE SILENT, Order of the Golden Fleece; son of FREDERICK HENRY, PRINCE OF ORANGE, the step-brother of MAURICE OF NASSAU, who was uncle of Frederick V of the Palatinate)

William III of England + Mary II of England (known as William and Mary, overthrew James II in Glorious Revolution)

James II & VII + Anne Hyde

Mary II of England + William III of England (see above)

Anne, Queen of Great Britain (succeeded by George I of England)

James II & VII + Mary of Modena

James Francis Edward Stuart (“The Old Pretender”) + Maria Clementina Sobieska (family related to Jacob Frank)

CHARLES EDWARD STUART (Bonnie Prince Charlie, "the Young Pretender")

HENRY BENEDICT STUART (Cardinal Duke of York)

Henrietta of England + PHILIPPE I, DUKE OF ORLEANS

CHRISTIAN IV OF DENMARK (knight of the Order of the Garter; hosted CHRISTIAN OF ANHALT, leader of the Rosicrucians, during his exile) + Anne Catherine of Brandenburg

In 1641, Henrietta Maria, accompanied by her daughter Mary, left England for The Hague, where her sister-in-law Elizabeth Stuart, widow of Frederick V of the Palatinate—whose marriage to Elizabeth Stuart was the basis of the Alchemical Wedding of the Rosicrucians—and mother of her old favorite, Prince Rupert (1619 – 1682), had been living for some years already. The Hague was the seat of William II, Prince of Orange (1626 – 1650), Mary’s first cousin, which she was to marry shortly afterwards. William II’s father was Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange (1584 – 1647), the son of William the Silent. Frederick Henry’s step-sister, Countess Louise Juliana of Nassau, was the mother of Frederick V. Henrietta Maria focused on raising money and in attempting to persuade Frederick Henry and Christian IV of Denmark to support Charles I’s cause.[33] Christian IV was the son of Frederick II of Denmark, whose interest in astrology supported the career of astronomer Tycho Brahe. Christian IV, a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, hosted the fugitive Christian of Anhalt, who masterminded the political agenda of the Rosicrucian movement. Christian’s brother, Augustus, Prince of Anhalt-Plötzkau, led a Rosicrucian court, and kept as his personal physician Baltazar Walther, whose travels to the Middle East inspired the legend of Christian Rosenkreutz and transmitted the knowledge of the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria to his pupil Jacob Boehme.[34]

Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange (1584 – 1647), the son of William the Silent, and and his family

William II, Prince of Orange (1626 – 1650) and Mary, Princess Royal, daughter of Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria, daughter of Henry IV of France and Marie de Medici

Frederick Henry was the sovereign prince of Orange and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 1625 until his death in 1647. The epoch of Frederick Henry is usually referred to by Dutch writers as the golden age of the Dutch Republic.[35] It was marked by great military triumphs, worldwide maritime and commercial expansion, and an outburst of productivity in art and literature. In 1648, after Frederick Henry’s illness and death caused a delay in the negotiations, the Lords States General of the United Netherlands and the Spanish Crown agreed to the Peace of Münster, part of the Peace of Westphalia, marking the end of both the Thirty Years’ War and the Eighty Years’ War, when the Dutch Republic was definitively recognized as an independent country no longer part of the Holy Roman Empire.

While the English Royal Family was in exile on the Continent, they had ample opportunity to meet members of the local Jewish community. Henrietta Maria had long enjoyed good relations with Jews. She included a Jewish favorite in her entourage, and patronized Jewish scholars who “practised divination through the medium of the Cabbalah.”[36] As explained by A.L. Shane, “the support of the Jewish merchants extended throughout the Royal Family’s exile and it was the Jewish merchants of Amsterdam who provided the money which the English Royal Family needed to finance their return to England, a fact which was gratefully acknowledged by Charles II, who promised to extend his protection to the Jews when he was restored to his kingdom.”[37] But the best demonstration of the Henrietta Maria’s interest in the Jewish community was her Royal visit to the Amsterdam Synagogue in 1642, accompanied by Frederick Henry, William III and new daughter-in-law. The visit was the occasion of the famous Address of Welcome of Menasseh ben Israel, which included a eulogy of the Queen, who was described as the “Worthy consort of the Most august Charles, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland.”[38]

Charles II (1630 – 1685) crowned at Westminster Abbey (1661).

Rabbi Jacob Judah Leon Templo (1603 – after 1675)

Soon after, Henrietta Maria visited the residence of Rabbi Jacob Judah Leon Templo (1603 – after 1675), a Jewish Dutch scholar, translator of the Psalms, and expert on heraldry, of Sephardic descent. Templo was born in Livorno, Italy, a stronghold of the Sabbatean movement, and would become Hakam in Middelburg and after 1643 in Amsterdam. His fascination with the Temple gained him the appellation, “Templo.” Templo wrote treatises about the Arc of the Covenant, and the form and nature of cherubim. His last work, a Spanish paraphrase of the Psalms, was dedicated to Isaac Senior Teixeira, financial agent of Queen Christina of Sweden.[39] In Amsterdam, Henrietta Maria examined his model of the Temple of Jerusalem and studied his explanatory pamphlet.[40]

Templo’s model was exhibited to public view at Paris and Vienna and afterwards in London. Templo had an introductory pamphlet prepared, whose title page bore a reproduction of the Royal Warrant or coat of arms of the English Royal Family with the well-known motto “Dieu et Mon Droit,” indicating Royal approval and patronage. The booklet was prefaced by a Dedication to Charles II, which read:

May it please your Sacred Majestie But the love of the Divine worship, that imparalel Pietie of your Majestie, known not only to your Brittains, but to all Europe, cals for the Protection, not of the most magnificent structures of this World, but of a building, though made with hands, yet that hath God Himself for the Architect thereof.[41]

Sir William Davidson (1614/5 – c. 1689) and his son

According to Jewish and Masonic historians in the eighteenth-century, Leon was welcomed by Charles II as a “brother Mason,” and he designed a coat of arms for the restored Stuart fraternity.[42] Despite ongoing criticism from London, the Stuart exiles in Holland continued to solicit Jewish support, while maintaining secretive contacts with sympathetic Freemasons in Britain. The Cromwellian apologist James Howell further accused the Stuarts of being descended from Jews who had found refuge in Scotland after their expulsion from England in 1290.[43] Howell also ridiculed what he claimed was the unpleasant odor of the Jews, who “much glory of their mysterious Cabal,” and he prayed that “England not be troubled with that scent again.”[44] In London the parliamentary writer Edward Spencer expressed his concern about rumors of collaboration between the Stuarts and the Jews, whom he warned not to be misled by their purported affinities nor by claims that Charles II is “your new Messias.”[45] These attacks only enhanced Jewish sympathy for Charles II, who further earned their support when he visited the synagogue in Frankfurt in 1655.[46] A year later, a delegation of prominent Jews in Amsterdam called on the Scottish agent John Middleton to pledge their secret financial and organizational assistance for the restoration effort.[47] In turn, Charles II promised them freedom to live and worship as Jews in Britain. To consolidate Jewish financial support, Charles called upon Sir William Davidson (1614/5 – c. 1689), a Scottish merchant and spy based in Amsterdam, who collaborated with Jewish trading partners.[48]

Augustus the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1579 – 1666), friend of Johann Valentin Andreae, reputed autor of the Rosicrucian manifestos

Equipped with recommendation letters from Constantijn Huygens, a confident of Moray and Davidson, to Christopher Wren and the Earl of Arlington, who were both also Masons, Templo reportedly met with the Charles II as a Masonic brother.[49] Huygens (1596 – 1687) was secretary to two Princes of Orange, Frederick Henry and William II. Huygens was the tutor of Frederick V and Elizabeth Stuart’s daughter, Elisabeth of Bohemia.[50] He was the father of the scientist Christiaan Huygens (1629 – 1695), who would become a member of the Royal Society. Constantijn referred fondly to his Hebrew studies with Templo.[51]

Templo had been assisted in the design of the Temple by Adam Boreel (1602 – 1665), an enthusiastic disciple of Jacob Boehme.[52] Boreel took a close interest in Judaism, working with Menasseh Ben Israel and Judah Leon Templo on editions of the Mishnah.[53] Boreel’s associates included the Sabbatean Peter Serrarius, John Dury, and Dury’s son-in-law Henry Oldenburg (c. 1619 – 1677), an original member of Samuel Hartlib’s Invisible College.[54] Serrarius had been able to convince both John Dury and Comenius of Sabbatai Zevi’s messiahship.[55] Oldenburg, a distinguished German savant who became the first secretary of the Royal Society, had kept a close watch on Zevi’s mission of, due to his interest in the restoration of the Jews.[56]

According to Willem Surenhuis (c.1664 – 1729) a Dutch Christian scholar of Hebrew, Templo “won the admiration of the highest and most eminent men of his day by exhibiting to antiquaries, and others interested in such matters, an elaborate model of the Temple of Jerusalem, constructed by himself.”[57] His renown inspired Augustus the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel—a member of the Fruitbearing Society and a close friend of Johann Valentin Andreae, the reputed author the Rosicrucian manifestos, to have his Hebrew treatise on the Temple translated into Latin by the German orientalist Johann Saubert (1638 – 1688), and to have Leon's portrait engraved.[58] Augustus’ first wife was Dorothea of Anhalt-Zerbst, the daughter of Christian of Anhalt’s brother, Rudolph, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst.

Bevis Marks Synagogue

Bevis Marks synaguoge, London

Davidson’s tolerance was greatly admired by a close friend of Rabbi Templo, Rabbi Jacob Abendana (1630 – 1685), who from 1680 until his death was Haham or Chief Rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese community.[59] Abendana was head of the first synagogue in England following the resettlement of 1656, the small Creechurch Lane Synagogue, located in the Aldgate Ward of the City of London. The actual founder of the synagogue was Antonio Fernandez Carvajal (c. 1590 – 1659), the first Jew to be admitted to England since the expulsion of 1290 and a close associate of Cromwell. Carvajal was the head of a secret congregation formed when a considerable number of Marrano merchants settled in London toward the middle of the seventh century. Outwardly, they passed as Spaniards and Catholics, but they held prayer-meetings at Creechurch Lane, and became known to the government as Jews by faith. They formed an important link in the network of trade with the Levant, East and West Indies, Canary Islands, and Brazil, and above all with the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal.

When Menasseh ben Israel came to England in 1655 to petition Parliament for the return of the Jews to England, Carvajal, though his own position was secured, associated himself with the petition. In 1656, Cromwell gave the Jews permission “to meet privately in their houses for prayer” and to lease a cemetery. Carvajal agreed with the church wardens of St. Katherine’s Creechurch for the lease of a house at 5 Creechurch Lane for about thirty Sephardi families from Spain and Portugal to use as a synagogue.[60] Carvajal and his comrades refused to appoint Menasseh as their community’s rabbi, choosing instead Carvajal’s cousin from Hamburg, Rabbi Moses Athias. Athias was succeeded by Jacob ben Aaron Sasportas (1610 – 1698), a Kabbalist and anti-Sabbatian, who had accompanied Menasseh ben Israel to London in 1655. Sasportas was followed by Abendana’s predecessor, another Amsterdam Rabbi, Joshua da Silva (d. 1679).

Abendana had already held that office in Amsterdam, but was born and spent most of his life in Hamburg, Germany. In Leyden, Abendana met Antonius Hulsius (1615 – 1685), who engaged with the mystic and pietistic separatist Jean de Labadie. With Hulsius, Abendana entered into a polemical discussion of Haggai 2:9, which Hulsius attempted to prove was a reference to the Church. Abendana responded with a Spanish translation of Rabbi Judah Halevi’s Kuzari, which he planned to dedicate to Davidson.[61] Kuzari takes the form of a dialogue between the king of the Khazars and a rabbi he invited to instruct him in the tenets of Judaism. Halevi’s treatise, explains Marsha Schuchard, “was especially relevant to the exiled Scottish Masons, for he utilized architectural terminology and demonstrated a method of ‘visual thinking’ by which the exiled Jews could regain imaginative access to their lost homeland and Temple.”[62] Arguing that Solomon was expert in all sciences, Halevi noted that “the roots and principles of all sciences were handed down from us,” especially through the Sefer Yetzirah:

To this [science of vision] belongs the “Book of Creation” by the Patriarch Abraham… Expansion, measure, weight, relation of movements, and musical harmony, all these are based on the number expressed by the word S’far. No building emerges from the hand of the architect unless its image had first existed in his soul.[63]

Abendana lauded Davidson’s tolerance and interest in Halevi’s “wholly intellectual and scientific” work.[64] Abendana praised Davidson as an embodiment of his Solomonic qualities, as well as Jewish capacity for loyalty to Charles II:

…your natural Lord and Master, who, absent from his opulent Provinces, has experienced in your worship the height to which Royal felicity can reach, in finding a vassal who by continued help has considerably relieved the cares of an offended Majesty, preserving, amid the tumult of the greatest disturbances, and of the most detestable ingratitude of many, the love which makes up for that of all others, and is constant both as regards the laws of nature and of duty.[65]

The Shochet to the Creechurch congregation from 1664 and its Hazan from 1667, Benjamin Levy, was described by Jewish historian Cecil Roth, as “a devoted adherent of the pseudo-Messiah Sabbatai Zevi, who received the first reports from abroad.”[66] According to David Katz, the “uncrowned king” of the Ashkenazi community in London was also named Benjamin Levy, who came to the city with other members of his family from Hamburg, the Ashkenazi equivalent of Amsterdam for the Sephardic community.[67] Benjamin was the son of Moses Levy, a wealthy merchant who numbered some of the best-known Rabbis among his connections. Levy was an original Subscriber to the Bank of England, and the only Jew on the list. It was also said that he had been responsible for procuring the new Charter for the East India Company in 1698, with the result that his name was the second on its registers.[68]

Solomon Ayllon (1660 or 1664 – 1728), the first of the successors of Shabbatai Zevi after Nathan of Gaza, and chief Rabbi of London

The Creechurch Lane Synagogue would later be known as the Bevis Marks Synagogue. In 1689, a Williamite bishop, Edward Stillingfleet (1635 – 1699), asked his Scottish visitor, Reverend Robert Kirk, about the Scottish phenomenon of second sight and the Mason Word. Rejecting Kirk’s explanation of second sight, Stillingfleet called it “the work of the devil” and then scorned the Mason Word as “a Rabbinical mystery.”[69] Provoked by this conversation, Kirk visited the Bevis Marks synagogue in London order to observe the ceremonies, which were led by Solomon Ayllon (1660 or 1664 – 1728), a follower of Sabbatai Zevi and the Haham or Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community of London.[70] After returning to Scotland, Kirk published his findings in 1691:

The Mason-Word, which tho some make a Misterie of it, I will not conceal a little of what I know; its like a Rabbinical tradition in a way of comment on Jachin and Boaz the two pillars erected in Solomon's Temple; with an addition of some secret signe delivered from hand to hand, by which they know and become familiar with another.[71]

Rabbi David Nieto (1654 – 1728)

According to a Sabbatean list of ordination, from a certificate held in the Schiff Collection at the New York Public Library, Ayllon was the first of the successors of Shabbatai Zevi after Nathan of Gaza.[72] Born in Salonica to a family of Spanish origin, Ayllon spent most of his life in Safed, Palestine, the center of Jewish mysticism. Sent on a mission to collect funds for the Jews of Palestine, Ayllon reached London, where he was offered the position of Haham. Ayllon succeeded Rabbi Jacob Judah Leon Templo’s friend, Jacob Abendana, as chief rabbi of the first synagogue in England, the small Creechurch Lane Synagogue, in the Aldgate Ward of the City of London, originally founded by Antonio Fernandez Carvajal, who was close Oliver Cromwell. Ayllon retained the position for fifteen years (1685–1700), but was under constant attack by the congregation of Bevis Marks for this his Sabbatean leanings, and finally resigned took and appointment as associate rabbi of the Sephardic congregation of Amsterdam.

Bevis Marks, the oldest Jewish house of worship in London, was established by the Sephardic Jews in 1698, when Rabbi David Nieto (1654 – 1728) took spiritual charge of the congregation of Creechurch Lane. Nieto was born in Venice, and first practiced as a physician and officiated as a Jewish preacher at Livorno, Italy, a stronghold of the Sabbatean sect. Nieto succeeded Ayllon as Haham in 1702.[73] In 1704, Nieto himself was accused of heresy, but he was defended by Tzvi Ashkenazi (1656 – 1718), known as the Chacham Tzvi, who served for some time as rabbi of Amsterdam, and was a resolute opponent of the followers of the Sabbatai Zevi.[74] Nieto’s works indicate that he was fully aware of the religious controversies of his time, including Spinozism and Sabbateanism. Nieto’s Esh Dat (1715) was directed against the Bosian Kabbalist and Sabbatean, Nehemiah Ḥiyya Hayyun (ca. 1650 – ca. 1730).[75]

Royal Society Fellows

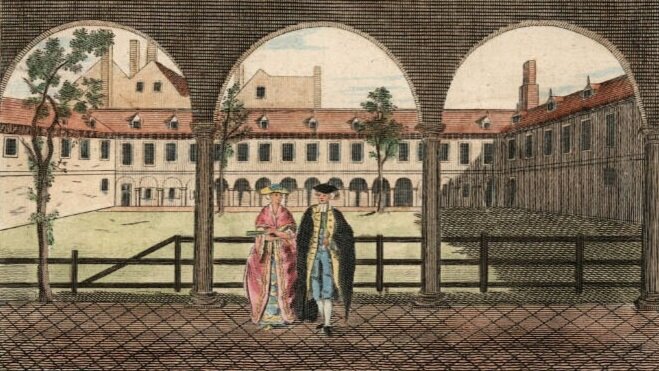

Gresham College, the first home of the Royal Society, had been set up in 1597 under the will of the founder of the Royal Exchange, Sir Thomas Gresham (1519-1579).

The Royal Society’s first charter (1662)

Robert Boyle (1627 – 1691)

Sir William Davidson worked closely with Robert Moray, Alexander Bruce, and other Scottish Freemasons.[76] Moray, a Scottish supporter of the Stuarts, who would serve as Colonel in the Scots Guard, was a student of Rosicrucianism and an ardent Freemason.[77] Moray was also well known to the cardinals Richelieu and Mazarin. Moray was probably familiar with Abendana’s work on Halevi, for he praised the writings of medieval Jews on mathematics, astronomy, and cosmology in his letters to his Masonic protégé, Alexander Bruce.[78] Moray further recommended the works of Christian Hebraists, such as Drusius, Joseph Scaliger, and Amama, who provided scholarly reinforcement for Scottish Masonic traditions. In 1572, Johannes van den Driesche, or Drusius (1550 – 1616), a student of Hebrew, became professor of Oriental languages at Oxford. Scaliger, a friend of Guillaume Postel, was associated, along with King James’ tutor George Buchanan, with Plantin Press, said to have operated as a front for a kind of “pre-Freemasonry.”[79] Drusius and Scaliger utilized their extensive research in Hebrew and Kabbalistic literature to argue that the Hassidim and Essenes, descendants of the Maccabeans, were a guild of religious craftsmen who played a key role in developing the mystical traditions of the Temple.[80] Drusius stressed the fraternal relationship between Solomon and Hiram, while Scaliger compared the Hasidim to contemporary craft guilds.[81]

According to Thomas De Quincey’s Historico-Critical Inquiry into the Origin of the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons (1886), the Rosicrucian Robert Fludd “it was, or whoever was the author of the ‘Summum Bonum,’ 1629, that must be considered as the immediate father of Freemasonry, as Andreä was its remote father.”[82] According to a statement made by John Wallis (1616 – 1703), some meetings organized in London in 1645, during the civil wars for enquiry into natural philosophy were the origin of the Royal Society. Amongst those who took part in these meetings were Theodore Haak, who was Comenius’ agent in England, a German from the Palatinate, and John Wilkins (1614 – 1672) who was later prominent in the Royal Society as Henry Oldenburg’s co-secretary.[83] Wilkins, chaplain to Frederick V of the Palatinate, was closely linked to Rosicrucianism in the Palatinate and tutored Frederick and Elizabeth’s son when he was sent to England.[84]

John Wilkins (1614 – 1672)

An admirer of Fludd, Wilkins’ work is placed clearly in the Rosicrucian tradition.[85] Wilkins quotes from the Rosicrucian Fama, and his Mathematicall Magick (1648) is largely based on the section on mechanics in Fludd’s Utriusque Cosmi Historia, published at Oppenheim in the Palatinate in 1619. In the preface to Mathematical and Philosophical Works, Wilkins praised the scientific works of Roger Bacon, Albertus Magnus, Agrippa, Dee, and Kircher, and denounced that “vulgar opinion attributes all such strange operations unto the power of Magick.”[86] Wilkins frequently mentions the “Lord Verulam” (Francis Bacon) in the book, or “Francis Rosicrosse.”[87] In 1648, meetings in Wilkins’ rooms at Wadham College at Oxford began which are stated by Thomas Sprat in his official to have been the origin of the Royal Society.[88] Among the members of this Oxford group were the alchemist Robert Boyle, William Petty, and Christopher Wren, England’s most famous architect, the designer of St Paul’s Cathedral. William Petty (1623 – 1687) became the personal secretary to Thomas Hobbes, allowing him contact with Descartes, Gassendi and Mersenne. He befriended Samuel Hartlib and Boyle.

Henry More (1614 – 1687), member of the Cambridge Platonists, who met with Menasseh ben Israel in London

According to Laursen and Popkin, “The publication of Henry Oldenburg’s and Robert Boyle’s correspondence has made it clear that millenarianism was at the center of the concerns of the Royal Society in its founding years.”[89] In 1647, Boyle had written to Samuel Hartlib mentioning his “Invisible College” and that he wished to support “so glorious a design.”[90] In 1663, the Invisible College became the Royal Society and the charter of incorporation granted by Charles II named Boyle a member of the council. The first secretary of the Royal Society was Henry Oldenburg, who forged a strong relationship with John Milton and his lifelong patron, Robert Boyle. Dury was connected to Boyle by his marriage to Dorothy Moore, an Irish Puritan widow. Their daughter, Dora Katherina Dury, later became the second wife of Henry Oldenburg. When Menaseh ben Israel arrived in London in 1650, Cromwell appointed a committee of important millenarian clergymen and government officials to receive him. Lady Ranelegh, Robert Boyle’s sister, had dinner parties for Menasseh, and Oldenburg met with him as well.[91] Menasseh also met with the Cambridge Platonists Ralph Cudworth (1617 – 1688) and Henry More (1614 – 1687). The Cambridge Platonists were a group of theologians and philosophers at the University of Cambridge in the middle of the seventeenth century. Frances Yates regarded the Cambridge Platonists as scholars who engaged with the Christian Kabbalah but rejected Hermeticism following Isaac Casaubon’s redating of the Hermetic corpus.[92]

Elias Ashmole (1617 –1692)

Among the first Freemasons on record were Sir Robert Moray and Elias Ashmole (1617 – 1692) who became original members of the Royal Society. Ashmole supported the royalist side during the English Civil War, and at the restoration of Charles II he was rewarded with several lucrative offices. His diary entry for October 16, 1646, reads in part: "I was made a Free Mason at Warrington in Lancashire, with Coll: Henry Mainwaring of Karincham [Kermincham] in Cheshire.”[93] In 1652, Ashmole befriended Solomon Franco, a Jewish convert to Anglicanism who combined his interest in Kabbalah and the architecture of the Temple with support for the English monarchy.[94] While Franco instructed him in Hebrew and was probably the source for his manuscript “Of the Cabalistic Doctrine,” Ashmole carried out intelligence work for the Stuart cause.[95] Also Stuart supporter, Franco believed in the Hebrew traditions of anointed kingship, and he looked for spiritual portents in the life of Charles II, with whose eventual restoration he was greatly pleased.[96] After the Restoration, Franco converted to Christianity, persuaded by his belief that God had a divine plan for Charles II. He gave a copy of his book to Ashmole.

Isaac Newton, a president of the Royal Society.

Ashmole was described by De Quincey as “one of the earliest Freemasons, [and] appears from his writings to have been a zealous Rosicrucian.”[97] Ashmole copied in his own hand an English translation of the Fama and the Confessio, and added a letter in Latin addressed to the “most illuminated Brothers of the Rose Cross,” petitioning them to be allowed him to join their fraternity. Ashmole had a strong Baconian leaning towards the study of nature.[98] He was an antiquary with a particular interest in the history of the Order of the Garter. Ashmole revered John Dee, whose writings he collected and whose alchemical and magical teachings he endeavoured to put into practice. In 1650, he published Fasciculus Chemicus under the anagrammatic pseudonym James Hasolle. This work was an English translation of two Latin alchemical works, one by Arthur Dee, the son of John Dee.

Ashmole’s works were avidly studied by other natural philosophers, such as Isaac Newton.[99] Newton, a president of the Royal Society, was committed to interpretations of the “Restoration” of the Jews to their own land of Palestine and spent the remaining years of his intellectual life exploring the Book of Daniel. In his library, Newton kept a heavily annotated copy of The Fame and Confession of the Fraternity R.C., Thomas Vaughan’s English translation of The Rosicrucian Manifestos. Newton’s writings suggest that one of the main goals of his alchemy may have been the discovery of the philosopher’s stone, and perhaps to a lesser extent, the discovery of the highly coveted Elixir of Life.[100] Newton also possessed copies of Themis Aurea and Symbola Aurea Mensae Duodecium by the alchemist Michael Maier. As a Bible scholar, Newton was initially interested in the sacred geometry of Solomon’s Temple, dedicating an entire chapter of The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended. Found within book are several passages that directly mention the land of Atlantis. Newton believed that before its corruption, a scientific priesthood secretly maintained the original primordial religion. In particular, the priests knew that the sun and not the earth was the center of their universe, and therefore the ancient temples from Stonehenge to the Temple in Jerusalem were organized around perpetual fires that represented the sun.[101]

Quakers

Quakers Meeting. Egbert van Heemskerk the Elder

In 1699, the Bevis Marks congregation signed a contract with Joseph Avis, a Quaker, for the construction of a new building, incorporating in the roof a beam from a royal ship presented by Queen Anne herself.[102] It has often been claimed that Quakers have been vastly over–represented among Fellows of the Royal Society.[103] Adam Boreel, who assisted Rabbi Templo in his famous design of the Temple of Solomon, is reputed to be the author of Lucerna Super Candelabrum (“The Light upon the Candlestick”), a mystical text accepted by both the Quakers and the Collegiants, also called the Amsterdam college, a society which he founded in 1646.[104] Their name is derived from their custom of calling their communities “Colleges,” as did Spener and the Pietists.[105] The Collegiants were a spiritualist cell, like those of Sebastian Franck (1499 – 1542/3) and Kaspar Schwenkfeld (1489 or 1490 – 1561), who presented the idea of an “invisible church,” and the idea that true Christianity was what he called the “inner light.”[106] Schwenkfeld was the founder of the Schwenkfelders, who had flourished in Görlitz in Boehme’s time there.[107] Luther referred to Franck as “the devil’s most cherished slanderous mouth.”[108] Franck was effectively a pantheist, who believed God to be immanent in nature. Franck made a distinction between what he called the “visible and “invisible” church. The “invisible church” derives from the Holy Spirit, through the hearts of all men. The concept would later be important to the Rosicrucians and Freemasons, and their heirs such as Schelling, Hölderlin and Hegel.[109]

The Landing of the Schwenkfelders, Adolph Pannash (1934).

George Fox (1624 – 1691)

In De Lammerenkrigh (1663), it is stated that “the majority of the Netherlands Quakers have first been Collegiants.”[110] The Quakers, also called Friends, are a historically Christian group of religious movements formally known as the Religious Society of Friends, Society of Friends or Friends Church. The movement was founded by George Fox (July 1624 – 1691) and his wife, Margaret Fell, popularly as the “mother of Quakerism.” Fox’s ministry expanded to North America and the Low Countries, though he was arrested and jailed numerous times for his beliefs. He spent his final decade working in London to organize his expanding movement. Despite objection from some Anglicans and Puritans, he was viewed with respect by Oliver Cromwell and the Quaker convert William Penn, son of Sir William Penn (1644 – 1718) who led Cromwell Western Design expedition which captured Jamaica in 1655, and founder of the State of Pennsylvania.

Margaret Fell or Margaret Fox (1614 – 1702)

William Penn (1644 – 1718)

Evidence of the influence of Jakob Boehme on the Quakers can be found in Fox’s writings. The nineteenth-century Quaker historian, Robert Barclay, printed passages from Fox’s Journal with parallel text from Boehme. Theodor Sippel spoke of Fox’s “free translation of Boehme’s writings.” William Braithwaite also cited a passage from the Journal where Fox claims an insight into the prelapsarian language of nature, and describes his mystical experience as involving a sense of smell, which was found in Boehme. Fox had met at least two of Boehme’s admirers, Durant Hotham and Morgan Lloyd. Hotman co-wrote a biography of Boehme with Abraham von Franckenberg, a friend of Balthasar Walther, and who also corresponded with Menasseh ben Israel.[111]

Elisabeth of Bohemia, the daughter of Elizabeth Stuart and Frederick V of the Palatinate, corresponded with a number of prominent Quakers, including Robert Barclay and William Penn. Penn became close friends with Elisabeth, celebrating her in the second edition of his book No Cross, No Crown. She is known to have been connected to Rosicrucian alchemist Francis Mercury van Helmont (1614 ‑ 1699).[112] Van Helmont had served on a diplomatic mission on behalf of Elisabeth who was living in Herford, Germany, when he met with Henry More and Robert Boyle. Van Helmont was a member of the circle around Rotterdam merchant Benjamin Furly, known as the Lantern, which included Lady Conway, Henry More, Adam Boreel and John Locke.[113] Furly was a Quaker and a close supporter of George Fox. In 1681, Penn, another member of Furly’s Lantern, was elected Fellow of the Royal Society.[114] Penn was personally acquainted with several members of the Royal Society, including John Wallis, Isaac Newton, John Locke, John Aubrey, Robert Hooke, John Dury and William Petty.[115]

Kabbalah Unveiled

Frontispiece to Jan Baptista van Helmont's The Origin of Medicine (1648), showing the younger Van Helmont partially obscured by his father Jan Baptist van Helmont

Newton was connected to van Helmont and the Christian Kabbalist Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (1636 – 1689), famous for his Kabbala Denudata (“Kabbalah Unveiled”), whose editors included Henry Oldenburg.[116] Von Rosenroth described Elijah as a “most famed prophet, an exemplary naturalist and sage and disdainful of riches.”[117] Elias Artista was also anticipated by van Helmont. In 1648, van Helmont published his father’s works. In the introduction, he speaks of his father's expectation that the arrival of Elias Artista was imminent. Helmont saw Paracelsus and himself as forerunners of Elias Artista and interpreted the progress that medicine had already made as confirmation of the advent of Elias Artista.[118]

Van Helmont and van Rosenroth were also both in contact with Serrarius.[119] Allison Coudert proposed that van Helmont and von Rosenroth, and to varying extents seventeenth-century natural philosophers who knew them or their work, including Leibniz and Newton, took a keen interest in Lurianic Kabbalah.[120] Every one of van Helmont’s books is a variation on the theme that a union of the Kabbalah and Christianity would provide a firm foundation for a universal religion, embracing Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and pagans.[121] Van Helmont acquired his knowledge of the Kabbalah from von Rosenroth, whom he helped to edit his Kabbala Denudata. Like their Christian-Kabbalist predecessors, van Helmont and von Rosenroth thought they could use the Kabbalah to verify Christian doctrine and thereby hasten the conversion of pagans and Jews.[122] Rosenroth’s intention in publishing the Kabbala Denudata was to supply a Latin translation of the Zohar. The Christian-Kabbalists of the Renaissance and later centuries viewed the Zohar in the same light as they did the Hermetica, the Sibylline Prophecies, the Orphica, and other such writings as prisca theologia, as far older than they actually were. They were believed to preserve vestiges of the “ancient wisdom” of the ancient Kabbalah, which God had revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai and which had been passed down from generation to generation.[123]

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646 – 1716)

Van Helmont was a friend of Gottfried Leibniz (1646 – 1716), who wrote his epitaph and introduced him to von Rosenroth in 1671.[124] Leibniz was a prominent German and philosopher and mathematician, whose most notable accomplishment was conceiving the ideas of differential and integral calculus, independently of Newton. His first position was as a salaried secretary to an alchemical society in Nuremberg.[125] In his youth Leibniz himself had joined an alchemical society at Nuremberg (in 1666–67), which had links with an earlier Rosicrucian network.[126] Leibniz had visited Queen Christina shortly before her death in 1689, and subsequently became a member of her Accademia fisico-matematica in Rome, which included many Rosicrucian elements.[127] Leibniz also met and admired her Rosicrucian collaborator Giuseppe Francesco Borri, and he lamented the alchemist’s later imprisonment by the Inquisition.[128]

In early in 1673, Leibniz was in England, where he came into contact with Henry Oldenburg. He was also welcomed by Moray, who introduced him to interested members, showed him the chemical-alchemical laboratory at Whitehall, and arranged the demonstration of Leibniz’s calculating machine. Moray proudly nominated him for Fellowship in the Royal Society. Leibniz later referred positively to other British Freemasons, such as John Evelyn and Wren. Evelyn, who had earlier investigated operative Masonry, contributed Masonic emblems to the Royal Society, and shared Masonic bonds with Moray.[129]

Anne Conway (1631 – 1679) was an English philosopher whose work, in the tradition of the Cambridge Platonists, was an influence on Leibniz. Her stepbrother, John Finch (1626 – 1682), who was ambassador of England to the Ottoman Empire and a fellow of the Royal Society, introduced her to the Cambridge Platonist Henry More. This led to a lifelong correspondence and close friendship between them on the subject of Descartes’ philosophy. She became interested in the Lurianic Kabbalah, and then was introduced by van Helmont to Quakerism, to which she converted in 1677.[130] In 1677, influenced by von Helmont, Conway wrote the Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, first published in Latin translation by van Helmont in Amsterdam in 1690. Conway collaborated with van Helmont on a Cabbalistical Dialogue (1682), for von Rosenroth’s Kabbala Denudata.

Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677), excommunicated from the Jewish community of Amsterdam in 1655 for heresy

In The Hague in 1676, Leibniz spent several days in intense discussion with Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677), a student of Menasseh ben Israel, who was also associated with the Rosicrucians, and who had just completed his masterwork, the Ethics.[131] In 1656, while Menasseh was away in London, the 23-year-old Spinoza was excommunicated from the Jewish community as a reviled heretic. Spinoza, a Jewish-Dutch philosopher of Portuguese Marrano origin. His Portuguese name was Benedito “Bento” de Espinosa or d’Espinosa. Along with René Descartes, whose doctrines he critiqued, Spinoza was a leading philosophical figure of the Dutch Golden Age, though his books were also later put on the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books. Spinoza developed highly controversial ideas regarding the authenticity of the Hebrew Bible and the nature of the Divine, and he came to be considered one of the great rationalists of seventeenth-century philosophy. He has been called the “prophet” and “prince” of pantheism, and the “God-intoxicated man.”[132]

In 1655, the Jewish religious authorities of Amsterdam issued a herem against him, excommunicating from the Jewish faith at age 23. In a language that was uniquely harsh for that kind of censure, the condemnation stated:

…having failed to make him mend his wicked ways, and, on the contrary, daily receiving more and more serious information about the abominable heresies which he practised and taught and about his monstrous deeds, and having for this numerous trustworthy witnesses who have deposed and borne witness to this effect in the presence of the said Espinoza, [council of elders] became convinced of the truth of the matter; and after all of this has been investigated in the presence of the honourable chachamin [sages], they have decided, with their consent, that the said Espinoza should be excommunicated and expelled from the people of Israel.”[133]

Spinoza is regarded as the first “secular Jew.”[134] Spinoza’s Tractatus put forth his most systematic critique of Judaism, and all organized religion in general. The Tractatus was one of the few books to be officially banned in the Netherlands at the time, though it could be purchased easily, and was soon the topic of heated discussion throughout Europe. Spinoza became the first to argue that the Bible is not historically accurate, that it is full of inconsistencies, and that some of its content can be explained through scientific study of the language. He contended that the Bible “is in parts imperfect, corrupt, erroneous, and inconsistent with itself, and that we possess but fragments of it.” He further argued that true religion has nothing to do with theology, ritual ceremonies, or sectarian dogma, and that religious authorities should have no role in governing a modern state. He also denied the reality of miracles and divine providence, reinterpreted the nature of prophecy, and called for tolerance and democracy.

The treatise also rejected the Jewish notion of Jewish “chosenness,” asserting all peoples are on par with each other, as God has not elevated one over the other. Spinoza also claimed that the Torah was essentially a political constitution of the ancient Israelites, and since the state no longer existed, its constitution was no longer valid. In his view, the Jews were not a community shaped by a shared theology, but a nationality that had been shaped by historical circumstances, and their common identity developed due to their separatism. The tangible symbol of their separateness, an its ultimate identifier, was circumcision. Spinoza also made what was later taken to be the earliest statement in support of the Zionist goal of creating a state in Israel.[135] In Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, he wrote:

Indeed, were it not that the fundamental principles of their religion discourage manliness, I would not hesitate to believe that they will one day, given the opportunity- such is the mutability of human affairs- establish once more their independent state, and that God will again choose them.[136]

Spinoza used the rose symbol on his personal seal.[137] The title page of his Tractatus is found the Latin phrase apud Henricum Kunraht, in reference to Heinrich Khunrath. Spinoza was in contact with and impressed by two Rosicrucians. First, there was Leibniz.[138] As well, Spinoza commented to in a letter to Jarig Jellis concerning Helvetius’ alchemical transmutation which he allegedly witnessed. Johann Friedrich Schweitzer, usually known as Helvetius had carried out the experiment following a visit from Elias Artista who provided him philosophers’ stone.[139] Spinoza’s well-known friend, Jan de Witt, the Grand Pensionary of Holland, was tutored at an early age by Isaac Beekman, a known Rosicrucian who associated with Descartes.[140]

After his separation from the Jewish community in 1656, Spinoza joined the Collegiants. Spinoza joined the Collegiants while living near Leiden from 1660 to 1663, during which time he began working on his major book, The Ethics.[141] Spinoza may have contributed to a link between the Quakers and the Sabbatean prophets.[142] It may very well have been the Sabbatean supporter Serrarius who, in 1657, introduced Spinoza to the Quakers, and in particular to their leader, Serrarius’ friend William Ames. Parallels between the behavior of the Shabbateans and the Quakers were recognized by their contemporaries.[143] In a Polish pamphlet of 1666, Sabbatai Zevi is actually called a “Quaker Jew.” In another pamphlet, a portrait of Zevi appears next to one of the “Quaker Jesus,” the English Quaker leader James Nayler (1618 – 1660).[144] In 1656, Nayler achieved national notoriety and was imprisoned and charged with blasphemy after he re-enacted Christ’s “Palm Sunday” entry into Jerusalem by entering Bristol on a horse.

Quaker missionaries were present in Izmir, Istanbul, and Jerusalem in 1657–58, shortly before the Sabbateans. They passed through Livorno, where they visited the synagogue and met with Jews who appeared to be interested in their message. From Livorno some of the missionaries traveled through Greece while others went to Izmir again. One of them reported that, “The sound [of our] coming is gone through this town among Turks and Jews and all.”[145] In 1658, the missionary Mary Fisher, who knew Margaret Fell personally, walked 500 miles alone through an unknown land in order to deliver a message from God before the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet IV. The Quaker’s most influential tool for the conversion of the Jews was a Hebrew translation of a Quaker pamphlet by Fell, entitled A Loving Salutation to the Seed of Abraham Among the Jews, which had been completed shortly before the trip, apparently by Spinoza. Spinoza translated a letter to Menasseh ben Israel from Fell, who also favored the return of the Jews to England.[146]

By the beginning of the 1660s, Spinoza’s name became more widely known, and he was eventually paid visits by Gottfried Leibniz, Hobbes and Henry Oldenburg.[147] Oldenburg had probably heard of Spinoza through their common friend, Serrarius.[148] Spinoza was also aware of Sabbatai’s missions, as he was interested in the possibility of a restoration of the Jews. As a pupil of Saul Levi Morteira, the Kabbalist rabbi Zacuto may also have been, as a youth still in Amsterdam, a fellow student of Spinoza.[149] In 1656, Morteira and da Fonseca were among the several Portuguese-Jewish elders the community in the Netherlands who excommunicated Spinoza. Also a follower of Zevi was Dionysius Musaphia (c. 1606 – 1675), a Jewish scholar and author of a number of scientific works regarding archaeology, Semite philology, and alchemy, and an adherent of Spinoza.[150] Even Spinoza himself entertained the possibility that with these events the Jews might reestablish their kingdom and again be the chosen of God.[151]

In later years, Serrarius handled the transmission of Spinoza’s manuscripts and letters to Oldenburg. From their correspondence, it is apparent that Oldenburg and Spinoza saw each other regularly during those years. Spinoza and Serrarius maintained their relationship until Serrarius’ death in 1669.[152] When he heard of the excitement about Sabbatai Zevi, Oldenburg wrote to Spinoza to enquire if the King of the Jews had arrived on the scene: “All the world here is talking of a rumour of the return of the Israelites… to their own country… Should the news be confirmed, it may bring about a revolution in all things.”[153] Oldenburg, who was keen to promote Spinoza’s ideas among the radical Protestants with whom he associated in England, put Spinoza into contact with Robert Boyle.

Empiricism

John Locke (1632-1704)

According to Yirmiyahu Yovel, author of The Other Within: The Marranos: Split Identity and Emerging Modernity, the Marrano experience contributed to the use of “dual language,” which deliberately employed equivocation, where terms and ideas had to be presented to appear to discuss one matter to outsiders, without disclosing their true meaning to for their intended audience, “set a linguistic pattern that played an indispensable role in the process of European modernization.” Thus Jewish esoteric ideas could be disguised as “Christian” or even secular philosophy. According to Yovel:

In perfecting the uses and modes of equivocation, the Marranos set a linguistic pattern that played an indispensable role in the process of European modernization… Hence we can say that some measure of marranesque element was indispensable in that evolution; the creators of modernity often had to act like quasi-Marranos. The Enlightenment in particular manifested this need—Hobbes and Spinoza, Hume and Shaftesbury, Diderot and Mandeville, Locke and Montaigne, the Deists, the materialists, possibly Boyle, even Kant (on religion) and Descartes (on his intended project), and a multitude of lesser figures and mediators found it necessary to revert to various techniques of masked writing.”[154]

Isaac La Peyrère, who was influenced by Thomas Hobbes, was an influence on Spinoza. Hobbes was also part of the circle around Descartes’ friend Marin Mersenne, Pierre Gassendi and Gabriel Naudé, to which La Peyrère belonged, and wrote a critique titled Meditations on First Philosophy of Descartes.[155] La Peyrère, Hobbes, and Spinoza are increasingly identified with the foundation of modern historical biblical criticism in the seventeenth century.[156] Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, which was published anonymously, borrowed and adapted freely from Hobbes’ Leviathan, whose themes were anticipated in De Cive (“On the citizen”).[157] The first seven chapters contain many borrowings from La Peyrère’s Prae-Adamitae.

Descartes laid the foundation for seventeenth-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Spinoza and Leibniz, and opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Hobbes was accused of atheism, or of teachings that could lead to atheism. He argued repeatedly that there are no incorporeal substances, and that all things, including human thoughts, and even God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, matter in motion.[158] Newton’s friend John Locke, (1632 – 1704), a prominent member of the Royal Society and a Freemason,[159] is the person normally considered as the founder of empiricism, a theory that states that knowledge comes only or primarily from sensory experience.[160] Most scholars trace the phrase “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” in the American Declaration of Independence, to Locke’s theory of rights. Following the tradition of Sir Francis Bacon, Locke is equally important to social contract theory. Locke was a member along with van Helmont of the Lantern of Benjamin Furly. Jacob Abendana’s brother Isaac who taught Hebrew at Cambridge and knew Locke, as well as Henry More and Robert Boyle.[161] Charles Cudworth’s daughter Damaris Cudworth (1659 – 1708), was a friend of Locke, and also a correspondent of Gottfried Leibniz.[162]

Locke, who also spent time in Amsterdam, was influenced by Spinoza.[163] The philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in Holland, Locke chose his friends of Spinoza, who “insisted on identifying himself through his religion of reason alone.” While she says that “Locke’s strong empiricist tendencies” would have “disinclined him to read a grandly metaphysical work such as Spinoza’s Ethics, in other ways he was deeply receptive to Spinoza’s ideas, most particularly to the rationalist’s well thought out argument for political and religious tolerance and the necessity of the separation of church and state.”[164]

Locke was a friend of John Aubrey, was close to Moray, Ashmole, and was familiar with Wren's role in the fraternity. Aubrey solicited information about the origins and nature of the Rosicrucians from his friend William Holder, Dean of Windsor.[165] In 1694, Aubrey’s Scottish correspondent Dr. James Garden sent from Aberdeen an account of the gift of second sight, which he connected with rumors of Rosicrucian activities in England: “as strange things are reported with you of 2d sighted men in Scotland so with us here of ye Rosicruzians in England.”[166] Aubrey allowed Locke to copy Garden's letter on both phenomena. With Wren and Boyle, Locke had earlier studied at Oxford under the Rosicrucian chemist Peter Sthael.[167] At Oxford, Aubrey had recently met John Toland, whose Rosicrucian activities in Scotland were described by their mutual acquaintance, the Oxford fellow Edmund Gibson, in 1694.[168] Toland agreed with Aubrey’s and Garden’s theories on the Druidic origins of Stonehenge.[169] By 1688, Locke was in touch with the editors Van Helmont and Knorr von Rosenroth, and the latter sent him a Kabbalistic commentary on the Abrégé of Locke’s forthcoming Essay Concerning Human Understanding. [170]

David Hume (1711 – 1776)

Locke is regarded as the “Father of Liberalism.”[171] One of Locke’s fundamental arguments against innate ideas is what he regarded as the very fact that there is no truth to which all people attest. Locke postulated that at birth man’s mind was a blank slate or tabula rasa, which is shaped by experience, sensations and reflections as the sources of all our ideas. Unlike Hobbes, however, Locke believed that human nature is characterized by reason and tolerance. But like Hobbes, he believed that human nature allowed men to be selfish. In a natural state all people were equal and independent, and everyone had a natural right to defend his “Life, Health, Liberty, or Possessions.” Also like Hobbes, Locke assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not enough, so people established a civil society to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government in a state of society.

Similar arguments were developed by Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711 – 1776), whose philosophy, especially his “science of man,” is often thought to be modeled on Newton’s successes in natural philosophy.[172] Beginning with his A Treatise of Human Nature, Hume strove to create an entirely naturalistic “science of man” that examined the psychological basis of human nature. He concluded that desire rather than reason governed human behavior, saying: “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions.” He argued against the existence of innate ideas, concluding instead that humans have knowledge only of things they directly experience. He was also a sentimentalist who held that ethics are based on feelings and governed by “custom” rather than abstract moral principles.

[1] David Katz. The Jews in the History of England (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994), p. 143.

[2] Michael Hunter. Establishing the New Science: the Experience of the Early Royal Society (Woodbridge: Boydell, l989), 17-21, 42, 115, 233.

[3] The Way of Light, trans. Campagnac, p. 3.

[4] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 268.

[5] Allison P. Coudert. “Kabbalistic Messianism versus Kabbalistic Enlightenment.” in M. Goldish, R.H. Popkin, Millenarianism and Messianism in Early Modern European Culture: Volume I: Jewish Messianism in the Early Modern World (Springer Science & Business Media, Mar. 9, 2013), p. 117.

[6] Herbert Breger. “Elias artista - a Precursor of the Messiah in Natural Science.” in Nineteen Eighty-Four: Science between Utopia and Dystopia, ed. Everett Mendelsohn and Helga Nowotny, Sociology of the Sciences, vol. 8 (New York: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1984), p. 49.

[7] Helene H. Armstrong, Francis Bacon - The Spear Shaker, (San Francisco, California: Golden Gate Press, 1985).

[8] Alfred Dodd. Francis Bacon’s Personal Life Story, Volume 2 - The Age of James (England: Rider & Co., 1949, 1986). pp. 157 - 158, 425, 502 - 503, 518 – 532.

[9] Journal of the Bacon Society, Volume 2 (George Redway, 1891), p. 176.

[10] John Henry. The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science (New York: St. Martin’s Press,

1997), p. 42.

[11] R.H Syfret (1948). “The Origins of the Royal Society.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. The Royal Society. 5 (2), p. 75.

[12] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, pp. 67-68.

[13] Frances Yates. “Science, Salvation, and the Cabala” New York Review of Books (May 27, 1976 issue).

[14] Eugenius Philalethes. Introitus apertus ad occlusum Regis Palatium (‘Entrance opened to the Closed Palace of the King’).

[15] Francis Bacon. Valerius Terminus, I, 580-581. Also: Bacon, De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum, IV, 1 (1623): Ego enim buccinator tantum, pugnam non ineo (“for I am but a trumpeter, not a combatant”).

[16] Francis Bacon. Novum Organum, I.xciii.

[17] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 203.

[18] Francis Bacon. Valerio Terminus Interpretation of Nature: with the annotations of Hermes Stella (1603), Ch. i.; cited in Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 185.

[19] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 185.

[20] Quoted by G. Rees, “Quantitative reasoning in Francis Bacon’s Natural Philosophy” (Nouvelks de la Republique de httres, 1985), pp. 38-39.

[21] Cited in Paolo Rossi. Francis Bacon: From Magic to Science (Oxon: Routledge, 2009), p. 22.

[22] Francis Bacon. Advancement of Learning (New York: P.F. Collier and Son, 1901), p. 169.

[23] Agassi, J (2012). “The missing link between bacon and the Royal Society.” The Very Idea of Modern Science, BSPS, 298, 157–166.

[24] Michael A. Peters & Tina Besley (2018). “The Royal Society, the making of ‘science’ and the social history of truth.” Educational Philosophy and Theory. p. 3.

[25] Keith Schuchard. “Judaized Scots, Jacobite Jews, and the Development of Cabalistic Freemasonry.”

[26] Vaughan Hart. Art and Magic in the Court of the Stuarts (London: Routledge, 1994); Marsha Keith Schuchard. “Dr. Samuel Jacob Falk,” p. 207.

[27] James Thompson & Saul Padover. Secret Diplmacy: Espionage and Cryptography (New York: Frederick Ungar, l963), p. 261.

[28] John Thorpe, “Old Masonic Manuscript. A Fragment,” Lodge of Research, No. 2429 Leicester. Transactions for the Year 1926-27, 40-48; Wallace McLeod. “Additions to the List of Old Charges,” Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, 96 (l983), pp. 98-99.

[29] D. Stevenson, Origins of Freemasonry, p. 163.

[30] Schuchard. “Judaized Scots, Jacobite Jews, and the Development of Cabalistic Freemasonry.”

[31] Samuel Guichenon. Histoire généalogique de la royale Maison de Savoie justifiée par Titres, Fondations de Monastères, Manuscripts, anciens Monuments, Histoires & autres preuves autentiques (Lyon, Guillaume Barbier, 1660), p. 708. Retrieved from http://cura.free.fr/dico3/1101cn135.html

[32] Diana Zahuranec. “Turin Legends: Royal Alchemy.” (August 23, 2015). Retrieved from https://dianazahuranec.com/2015/08/23/turin-legends-royal-alchemy/

[33] C. V. Wedgwood. The King’s War: 1641–1647 (London: Fontana, 1970), pp. 78–9.

[34] Penman. “A Second Christian Rosencreuz?” p. 162.

[35] George Edmundson. “Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange.” The English Historical Review 5, no. 17 (1890): 41-64.

[36] James Picciotto. Sketches of Anglo-Jewish History, ed. Israel Finestine (1875; rev. ed. Soncino Press, l956), 41; Cecil Roth. “The Middle Period of Anglo-Jewish History (1290-1655) Reconsidered,” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England, 19 (1955-59), p. 11.

[37] A. L. Shane. “Rabbi Jacob Judah Leon (Templo) of Amsterdam (1603—1675) and his connections with England.” Transactions & Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England) , 1973-1975, Vol. 25 (1973-1975), pp. 120-123.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Gotthard Deutsch & Meyer Kayserling. “Leon (Leao).” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[40] Arthur Shane, “Jacob Judah Leon of Amsterdam (1602-1675) and his Models of the Temple of Solomon and the Tabernacle,” Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, 96 (1983), pp. 146-69.

[41] Vera Keller. Knowledge and the Public Interest, 1575–1725 (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 89.

[42] Ibid.

[43] J. Howell, History, Epistle Dedicatory.

[44] J. Milton, Works of John Milton, V, 68.

[45] Sir Edward Spencer. A Breife Epistle to the Learned Menasseh ben Israel, in Answere to his, dedicated to the Parliament (London, 1650), p. 248.

[46] Edward Nicholas. The Nicholas Papers, ed. George Warner (London: Camden Society, 1892), III, p. 51.

[47] C.H. Firth, Scotland and the Protectorate (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1899), pp. 342-43.

[48] Wilfrid Samuel. “Sir William Davidson, Royalist, and the Jews,” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England, 14 (l940), pp. 39-79.

[49] Marsha Keith Schuchard. “Dr. Samuel Jacob Falk: A Sabbatian Adventurer in the Masonic Underground.” Millenarianism and Messianism in Early Modern European Culture, Volume I, p. 208.

[50] Lisa Shapiro. “Elisabeth, Princess of Bohemia.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/elisabeth-bohemia

[51] Keith Schuchard. “Dr. Samuel Jacob Falk: A Sabbatian Adventurer in the Masonic Underground.”

[52] Geoffrey F. Nuttall. “Early Quakerism in the Netherlands: Its Wider Context.” Bulletin of Friends Historical Association, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Spring 1955), p. 5.

[53] J.T. Young. Faith. Alchemy and Natural Philosophy: Johann Moriaen, Reformed Intelligencer, and the Hartlib Circle (1998), p.47.

[54] Jonathan Israel. The Dutch Republic (1995), pp. 587-591.

[55] Mark Greengrass, Michael Leslie & Timothy Raylor, editors. Samuel Hartlib and Universal Reformation: Studies in Intellectual Communication (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) p. 134.

[56] Marsha Keith Schuchard. Emanuel Swedenborg, Secret Agent on Earth and in Heaven (Leiden: Brill, 2011) p. 22.

[57] A. L. Shane. “Rabbi Jacob Judah Leon (Templo) of Amsterdam (1603—1675) and his connections with England.” Transactions & Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England) , 1973-1975, Vol. 25 (1973-1975), pp. 120-123.

[58] Faith. Alchemy and Natural Philosophy, p.47.

[59] Schuchard. Restoring the Temple of Vision, p. 550.

[60] Derek Taylor. “British Chief Rabbis 1664-2006,” p 15.

[61] Judah Halevi. Cuzary, trans. from Hebrew to Spanish by Jacob Abendana (Amsterdam, 1663).

[62] Eliott Wolfson. Through a Speculum that Shines: Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish Mysticism (Princeton: Princeton UP, l994), pp. 50-167.

[63] Judah Halevi. The Kuzari (ed.) Henry Slonimsky (New York, l964), 228.

[64] Wilfrid Samuel. “Sir William Davidson, Royalist, and the Jews,” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England, 14 (l940), pp. 40-41, 65-66.

[65] ibid., 40-41.

[66] Cecil Roth. History of the Great Synagogue (1950). Retrieved from https://www.jewishgen.org/jcr-uk/susser/roth/chone.htm

[67] David S. Katz. The Jews in the History of England 1585–1850 (Clarendon Press, 1994), p. 180.

[68] Cecil Roth. History of the Great Synagogue (1950). Retrieved from https://www.jewishgen.org/jcr-uk/susser/roth/chone.htm

[69]. Robert Kirk. The Secret Commonwealth (1691), ed. S. Sanderson (London, l976), 88-89; D. Stevenson, Origins of Freemasonry, pp. 133-34.

[70]. David Katz. The Jews in the History of England (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994), pp. 161-62, cited in Marsha Keith Schuchard. “Judaized Scots, Jacobite Jews, and the Development of Cabalistic Freemasonry”; Louis Ginzberg. “Ayllon, Solomon ben Jacob.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[71]. Kirk. The Secret Commonwealth, pp. 88-89.

[72] Rabbi Antelman. To Eliminate the Opiate. Volume 2 (Jerusalem: Zionist Book Club, 2002). p. 102.

[73] Louis Ginzberg. “Ayllon, Solomon ben Jacob.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[74] Rabbi Yosef Prager. “The Early Years of London’s Ashkenazi Community.” Yerushaseinu, Fifth Yearbook; Rabbi Yosef Prager. The Early Years of London’s Ashkenazi Community. Yerushaseinu, Fifth Yearbook; See Evelyne Oliel-Grausz, “A study in intercommunal relations in the Sephardi Diaspora: London and Amsterdam in the eighteenth century”, in Dutch Jews as perceived by themselves and by others: proceedings of the eighth international symposium on the history of the Jews in the Netherlands (Leiden, 2001), p. 4; Solomon B. Freehof, “David Nieto and Pantheism”, in A Treasury of Responsa (Philadelphia, 1963), pp. 176-181.

[75] Solomons. David Nieto and Some of his Contemporaries (1931); A.M. Hyamson. Sephardim of England (1950), index; J.J. Petuchowski. Theology of Haham David Nieto (1954); D. Nieto. Ha-Kuzari ha-Sheni (1958), introd. by J.L. Maimon, 5–20, biography by C. Roth, pp. 261–75.

[76] On Moray’s collaboration with Davidson, see NLS: Kincardine MS. 5049, ff.3, 28; MS. 5050, ff.49, 55. On the Jewish initiations, see Samuel Oppenheim, “The Jews and Masonry in the United States before 1810," Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, 19 (1910), pp. 9-17; David Katz, Sabbath and Sectarianism in Seventeenth-Century England (Leiden: Brill, l988), pp. 155-64.

[77] Alexander Robertson. The Life of Sir Robert Moray (London: Longman's Green, l922); David Stevenson, “Masonry, Symbolism, and Ethics in the Life of Sir Robert Moray,” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 114 (l984), pp. 405-31.

[78] NLS: Kincardine MS. 5049, ff. 117, 151; MS. 5050, f. 28.

[79] Schuchard. Restoring the Temple of Vision, p. 178-179.

[80] Anthony Grafton. Joseph Scaliger (Oxford: Clarendon, l983), I, p. 226, II, pp. 183, 299-324.

[81] Johannes Drusius. Ad Minerval Serarrii Rsponsio, 19; published in Elohim sive de nomine Dei (Frankerae, 1604). Joseph Scaliger, Elenchus Tri haeressii Nicolaus Serrarius, 30; published in Sixtini Amama's edition of Drusius' De Tribus Sectis Judaeorum (1619).

[82] Cited in William Francis C. Wigston. Francis Bacon, Poet, Prophet, Philosopher, Versus Phantom Captain Shakespeare, the Rosicrucian Mask (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, 1891), p. 205.

[83] Yates. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, pp. 175-6.

[84] Hagger. The Secret Founding of America, p. 122-4.

[85] Marsha Keith Schuchard. Emanuel Swedenborg, Secret Agent on Earth and in Heaven (Leiden: Brill, 2011) p. 65.

[86] Ibid.

[87] John Wilkins. Mathematicall Magick, or, The Wonders that may be Performed by Mechanicall Geometry (London, 1648), pp. 256–7.

[88] Thomas Sprat. History of the Royal Society (London, 1667), pp. 53 ff.

[89] J.C. Laursen & R.H. Popkin. “Introduction.” In Millenarianism and Messianism in Early Modern European Culture, Volume IV, ed. J.C. Laursen & R.H. Popkin (Springer Science+Business Media, 2001), p. xvii.

[90] Margery Purver. The Royal Society: Concept and Creation (1967), Part II Chapter 3, “The Invisible College.”