5. The Invisible College

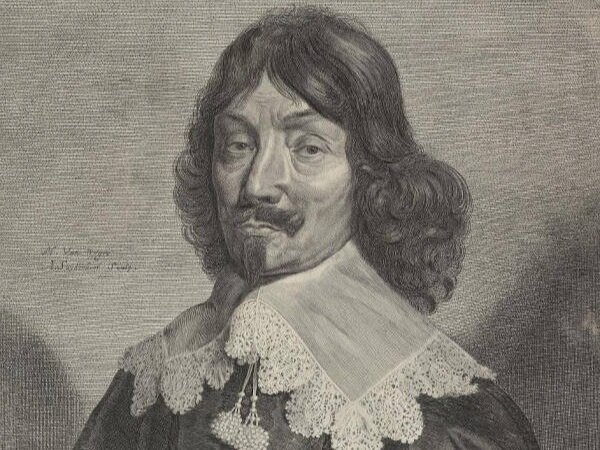

Lion of the North

Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden

In the years following the outbreak of the Thirty Years War in 1618, the combination of Hapsburg power with Catholic Counter Reformation came near to complete victory. However, after ten years of war, the victories of Gustavus Adolphus (1594 – 1632), King of Sweden, of the House of Vasa, saved the Protestant cause. Through his mother, Catherine Jagiellon, Gustavus Adolphus was the grandson of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, whose wife, Christine of Saxony, was the great-great-granddaughter of Emperor Sigismund and Barbara of Celje, founders of the Order of the Dragon. Gustavus Adolphus’ father was Charles IX of Sweden, whose brother was John III of Sweden, whose son Sigismund III Vasa supported the famous Polish alchemist Michael Sendivogius, who was associated with John Dee. John III’s wife was Catherine Jagiellon was the daughter of Sigismund I the Old, a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, and Bona Sforza. Catherine’s sister Anna Jagiellon married Stephen Báthory, sponsor of John Dee and uncle of Elizabeth Báthory, the “Blood Countess.” Their brother Sigismund II Augustus married Barbara Radziwiłł, who was accused of promiscuity and witchcraft. Gustavus Adolphus married Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg, the granddaughter of Albert, Duke of Prussia, Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, and founder of the Duchy of Prussia.

Genealogy of Queen Christina

Gustav I of Sweden King of Sweden (previously self-recognised Protector of the Realm from 1521, during the ongoing Swedish War of Liberation against King Christian II of Denmark, Norway and Sweden) + Margaret Leijonhufvud

John III of Sweden + Catherine Jagiellon (daughter of Sigismund I the Old, Order of the Golden Fleece, who married Bona Sforza. Sister of Sigismund II Augustus who married Barbara Radziwiłł who was accused of promiscuity and witchcraft. And sister of Anna Jagiellon, wife of Stephen Báthory, sponsor of John Dee and uncle of Elizabeth Báthory, the “Blood Countess”)

Sigismund III Vasa (from whom the Vasa kings of Poland were descended. Raised by Jesuits, sponsored alchemist Sendivogius) + Anne of Austria (see above)

Władysław IV Vasa (Abraham von Franckenberg presented to his court a list the great Christian Kabbalists of history appended to Guillaume Postel’s Absconditomm a Constitutione Mundi Clavis)

Charles IX of Sweden + Maria of the Palatinate (sister of Frederick IV, Elector Palatine, father of Frederick V of the Palatinate of the Alchemical Wedding)

Charles IX of Sweden + Christine of Hesse (daughter of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse and his spouse Christine of Saxony)

GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS (“Lion of the North”) + Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg

QUEEN CHRISTINA OF SWEDEN

Through his mother, Gustavus Adolphus was also a second cousin of Frederick IV, Elector Palatine, whose marriage to Elizabeth Stuart was celebrated by the Rosicrucians as an Alchemical Wedding. Frederick V, who had represented the hope of the Rosicrucians, returned to Germany, and was recognized by Gustavus as leader of the Protestant princes. While Frederick V was seen by the Rosicrucians as the Winter Lion, inspired by a prophecy by Paracelsus, Gustav was seen as the incarnation of “the Lion of the North,” or as he is called in German Der Löwe aus Mitternacht (“The Lion of Midnight”). This image of an all-conquering mystical hero descending from the North to inflict God’s wrath on his opponents had roots in Old Testament prophecy, foretold by Jeremiah, with new life breathed into it in the sixteenth century through an apocalyptic vision attributed to Paracelsus and Tycho Brahe that foresaw the northern hero laying low the eagle, the symbol of the Habsburgs and returning peace to the world after an era of unprecedented suffering and preparing the way for the second coming.[1] The theme recurs in Guillaume Postel and Tommaso Campanella.[2] The prophecy of the “Lion of Midnight” was first mentioned in 1605 a letter to Gustavus’ father, King Carl IX of Sweden, from Michel Lotich, who pointed to a new era heralded by the new star of 1572. He drew the sign of Cassiopeia and placed beside it a sword topped with a star. The sword stood on an altar inscribed with the sign of Leo.[3] The Rosicrucian Confessio stated, “our treasures shall remain untouched and unstirred, until the Lion doth come, who will ask them for his use, and employ them for the confirmation and establishment of his kingdom.”[4]

Elisabeth of the Palatinate (1618 – 1680), also known as Elisabeth of Bohemia, the eldest daughter of Frederick V, Elector Palatine and Elizabeth Stuart.

When Frederick V died in November 1632, his widow, the Queen of Bohemia, Elizabeth Stuart, living in refuge in The Hague, represented for sympathizers in England the policy of support for Protestant Europe which, in their opinion, should have been the policy of King James I towards his daughter and son-in-law.[5] In years to come, it was through Elizabeth’s descendants that a Protestant succession was to be sought. If her brother Charles I had had no children, or had his children died before him, Elizabeth would have succeeded, or if herself no longer alive, her eldest son would have succeeded to the throne as Queen of Great Britain. Her daughter, was to become Sophia of Brunswick, Electress of Hanover, whose son, George I, was the first Hanoverian king of Great Britain. Elizabeth’s diplomatic supporters were Sir William Boswell, executor of Francis Bacon, now ambassador at The Hague, and Sir Thomas Roe, former ambassador to Gustavus Adolphus, and Chancellor of the Order of the Garter.[6] Gustav’s mother was Christina of Holstein-Gottorp, whose uncle was Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, Frederick V’s close friend.

Of thirteen children and eldest daughter of Frederick V and Elisabeth Stuart was Elisabeth, Princess of Bohemia (1618–1680). It is reported that her intellectual accomplishments earned her the nickname “La Greque” from her siblings, and might well have been tutored by Constantijn Huygens.[7] Descartes dedicated his Principles of Philosophy to her, and wrote his Passions of the Soul at her request. She seems to have been involved in negotiations around the Treaty of Westphalia and in efforts to restore the English monarchy after the English civil war. As Abbess of the convent in Herford, Germany, she managed the rebuilding of that war-impacted community and also provided refuge to marginalized Protestant religious sects, affiliated with the Rosicrucians including Labadists and Quakers.

Elisabeth’s older brother Charles Louis (1617 – 28 August 1680) spent much of the 1630s at the court of his maternal uncle, Charles I of England, hoping to enlist English support for his cause. Their brother Rupert (1619 – 1682), gained fame for his chemical experiments as well as for his military and entrepreneurial exploits, including the founding of the Hudson’s Bay Company. He also played a role in the early African slave trade. Louise Hollandine (1622 – 1709), was an accomplished painter and student of Gerritt van Honthorst. Sophia (1630 – 1714), who became the electress of Hanover, was renowned for her intellectual patronage, particularly of Leibniz and John Toland.[8] She was well-read in the works of Descartes and Spinoza.

Hartlib Circle

John Amos Comenius (1592 – 1670).

Elizabeth was the chief patron the “three foreigners,” Samuel Hartlib (c. 1600 – 1662), John Dury (1596 – 1680) and John Amos Comenius (1592 – 1670), all three “millenarian Baconians” and members of a Rosicrucian “Invisible College” who were responsible in fanning millenarian ideas among the English Puritans about the approach of the Messianic time that became popular in the seventeenth century.[9] Hartlib, who had been captivated by Baconian ideas had come to England in 1628, after the Catholic conquest of Elbing in Polish Prussia, as part of the disruptions of the Thirty Years’ War. He seems to have studied as young in Cambridge where he had been captivated by the ideas of Francis Bacon.[10]

Hartlib had been the head of a mystical group like Andreae’s Christian Unions, a cover for the Invisible College, which pursued Rosicrucian ideals. Ever since 1620, the year of collapse of the Rosicrucian movement, Hartlib and his friends had dreamed of establishing “models” of Christian society, based in Andreae’s Christianopolis. They called it “Antilia” or “Macaria.” The former name came from Andreae’s work, the latter from More’s Utopia.[11] In Hartlib’s A Description of the Famous Kingdom of Macaria, published in 1641, that ideal “model” was the first step to “the reformation of the whole world.”[12] The plan for Andreae’s Societas Christiana was already set forth in two works that were believed to have been lost until they were discovered recently among the Hartlib papers.[13]

John Milton (1608 – 1674)

Not known in his own day for his published writings, Hartlib was virtually forgotten by historians, until the rediscovery of an archive of his personal papers. The Hartlib papers revealed his personal correspondence to have been extensive. It ranged from Eastern and Central as well as Western Europe, Great Britain and Ireland and New England. Among the extensive network of the Hartlib Circle were John Milton, author of Paradise Lost, a friend of Rosicrucian and Cromwellian Andrew Marvell, and John Winthrop, one of the leading figures in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Recent scholarship has been pointing to Fludd as probably a main influence on Milton’s world of angels and demons.[14] Lucifer’s statement in Milton’s Paradise Lost, “Better to reign in hell, than serve in heav’n,” became an inspiration for those who embraced the rebellion against God. According to Matthews in Modern Satanism, “Shorn of all theistic implications, modern Satanism’s use of Satan is firmly in the tradition that John Milton inadvertently engendered—a representation of the noble rebel, the principled challenger of illegitimate power.”[15] As noted by Frances Yates, that there was an influence of Kabbalah on Milton is now generally recognised. Denis Saurat believed that he had found traces of Lurianic Kabbalah in Paradise Lost.[16] In 1955, the eminent Hebrew scholar Zwi Werblowsky stated that although the influence of Lurianic Kabbalah on Milton could not be proved, there was decidedly an influence of Christian Kabbalah upon him: “Milton is influenced not by the Lurianic tsimtsum, still less by the Zohar, but by Christian post-Renaissance Cabala in its pre-Lurianic phase.”[17]

Dury also came from Elbing, where he had met Hartlib and discovered that he also was a Baconian.[18] When he arrived in England, Hartlib collected around him refugees from Poland, Bohemia and the Palatinate. John Dury, a Scotsman, met Hartlib at Elbing and was closely in touch with Elisabeth of Bohemia, and with her adviser Sir Thomas Roe, the advocate of English intervention in the Thirty Years’ War and took an active interest in the restoration of her son, Charles Louis, to the Palatinate, as did Hartlib. “Protestant unity,” Dury wrote to the English Court, “will be more worth to the Prince Palatine than the strongest army that His Majesty can raise him.”[19] John Dury spent a considerable amount of time in Sweden, where he exercised a strong influenced on Gustav Adolphus.[20] As travelled over Europe, he ever supported by the ‘‘agitation and cooperating industry’’ of Hartlib in London, ‘‘the boss of the wheel,’’ as Dury called him, ‘‘supporting the axle-tree of the chariot of Israel.’’[21]

At the end of Comenius’ Labyrinth of the World, a pilgrim escapes from the maze of worldly events and finds himself in “the Paradise of the Heart.” There, angelic teachers impart him with “secret knowledge of diverse things.” Similar angelic teachers were found in Andreae’s Christianopolis. Comenius referred to these angelic teachers as an “invisible college.”[22]

As a consequence of the Thirty Years’ War, Comenius lost all his property and his writings in 1621, and six years later he led the Bohemian Brethren into exile in Poland. There he too discovered the works of Francis Bacon and become an enthusiast.[23] Comenius was a Bishop of the Bohemian Brethren, heirs of the Hussite movement. The Hussites were a pre-Protestant movement that followed the teachings of Czech reformer Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake at the Coucil of Constance in 1415, despite the protection he received from King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia and his brother Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, and founder of the Order of the Dragon.[24]

Comenius was present in the cathedral during the ceremony when Frederick was crowned King of Bohemia in defiance of the Catholic Habsburgs.[25] Comenius met with the defeated Frederick V in The Hague to share with him prophecies outlined in a work called Lux in Tenebris (“Light in Darkness”).[26] It contained the pronouncements of three prophets, one of whom named Christopher Kotter who promised the future restoration of Frederick to the Kingdom of Bohemia. Kotter’s visions were apparently brought to him by “angels” who would suddenly make themselves visible, show him a vision and then disappear. Comenius named Johann Valentin Andreae, the purported author of the Rosicrucian manifestoes, as one of those who inspired him towards the reform of education. Andreae recognized Comenius as his intellectual heir and encouraged him to carry on his reforming Rosicrucian ideas.[27] It was to Andreae’s “golden book,” Comenius afterwards wrote, that he owed “almost the very elements” of the ideas which summarized under the name “Pansophia.”[28] In 1642, Descartes met Comenius at Endegeest near Leyden, Holland. The meeting was arranged by Hartlib, a mutual friend.[29] However, they disagreed with each other’s philosophical approaches, and Comenius was later to write scathing critiques of Cartesian philosophy.

Gothic Kabbalah

Johannes Thomae Bureus Agrivillensis (Johan Bure) (1568–1652).

Like Comenius, Descartes was in contact with Queen Christina (1626 – 1689) of Sweden, the only surviving legitimate child of King Gustav Adolphus, and an avid student of the occult. Known as the “Minerva of the North,” Christina is remembered as one of the most learned women of the seventeenth century.[30] The symbolism of the “Lion of the North,” was advanced for propaganda purposes by Gustavus’ renowned teacher, the Runic Swedish scholar and Rosicrucian, Johannes Bureus (1568-1652), who was in frequent contact with Abraham von Franckenberg, a close friend and biographer of Balthasar Walther, who inspired the legend of Christian Rosenkreutz. Bureus is primarily known as an exponent of early modern “Gothicism,” the idea that the ancient Goths of Scandinavia were the first rulers of Europe, and Sweden the true origin of Western culture. A practicing alchemist, Bureus was interested in Paracelsus and the Neoplatonic revival of the Renaissance, he viewed alchemy as part of a prisca theologia stemming from the ancient Goths, arguing that the Scandinavian runes constituted a “Gothic Cabala.”[31] Bureus had begun to draft his system in 1605, and applied John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica to his construction of a Runic Cross in 1610. In 1609-1610, Bureus started to adapt the views of the Hermetic philosophers to his runic philosophy, excerpting from Pico’s Heptaplus, Ficino’s expositions of the triads in the late Platonic commentaries by Porphyry and Proclus, and from the Hermetic Pimander. He drew on Christian Kabbalists like Reuchlin and read Roeslin’s Copernican and Paracelsian compendium De Nova Mundi Hypotheses (1598). He drew up a Kabbalistic Tree of Life and emphasized the correspondences of the seven planets to the seven lower Sephira, which he contemplated using on a coat-of-arms.[32]

Bureus highlighted the affinities among the early Rosicrucians to the doctrine of a universal human restitution set out by Guillaume Postel. Bureus’ copy of Postel’s Panthenousia is marked up with comments, especially in the sections on Arabic and on a possible concordance between the Hebrews, the Christians, and the Ismailis. Postel’s scheme employed rhetoric about the redemptive role to be played for mankind by the sons of Japheth, particularly Gomer and his youngest brother Ashkenaz.[33] Bureus expanded on Postel’s claims concerning the dual sources of prophecy: that the Old Testament prophets are completed by the Sibylline oracles, and of the role of Alruna, the northern Sybil, who like the Celtic druids had been revered for her prophetic powers. Alruna was born in 432 B.C. and Bureus believed she knew the great Thracian Sibyls, Latona, Amalthea, and Acheia.[34] In personal notes dated as early as 1609-1611, Bureus works out a mystical sevenfold iconography based on the ancient runes, inspired by millenarian and Kabbalistic texts, and in particular by the hieroglyphic monad of John Dee, which by 1610 emerges as the main pattern for Bureus’ theosophic tool, the Adulruna, which he presents as an alternate name for the Philosopher’s Stone.[35]

On this 1570 map, Hyperborea is shown as an Arctic continent and described as "Terra Septemtrionalis Incognita" (Unknown Northern Land).

Bureus was inspired by Postel’s ideas on a revival of Celtic Europe with an accompanying revolution of arts and sciences, to which he added ideas on the northern spread of the Hyperborean peoples. Along with Thule, Hyperborea was one of several terrae incognitae to the Greeks and Romans, where Pliny, Pindar and Herodotus, as well as Virgil and Cicero, reported that the sun was supposed to rise and set only once a year, and people lived to the age of one thousand and enjoyed lives of complete happiness. Hecataeus of Abdera published a lengthy treatise of all the stories about the Hyperboreans current in the fourth century BC, preserved by Diodorus Siculus (fl. first century BC). Theopompus (c. 380 BC – c. 315 BC), in his work Philippica, claimed Hyperborea was once planned to be conquered by a large race of soldiers from another island—some have claimed this was Atlantis—the plan though was abandoned because the soldiers from Meropis realized the Hyperboreans were too strong for them and the most blessed of people. Theseus, the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens, was said to have visited the Hyperboreans and Pindar (c. 518 – 438 BC) transferred Perseus’ encounter with Medusa there from its traditional site in Libya. Apollonius of Rhodes (fl. first half of 3rd century BC) wrote that the Argonauts sighted Hyperborea, when they sailed through Eridanos, a river in northern Europe mentioned in Greek mythology. Hyperborea was identified with Britain first by Hecataeus of Abdera. Six classical Greek authors also came to identify the Hyperboreans with the Celts: Antimachus of Colophon, Protarchus, Heraclides Ponticus, Hecataeus of Abdera, Apollonius of Rhodes and Posidonius of Apamea.

Addressing himself to the Rosicrucians, Bureus proclaimed in his FaMa e sCanzIa reDUX (1616) that the north belonged to a distinct Hyperborean tradition that was preserved in the Gothic-Scandinavian Runes. As early as 1434, Bishop Nicolaus Ragvaldi (c. 1380 – 1448) had claimed that Sweden was the cradle of European culture, since virtually all the peoples of Europe, including the Huns, the Wends, the Lombards, and the Saxons, were descendants of the ancient Goths of Scandinavia. A century later, Archbishop Johannes Magnus (1488 – 1544) traced the birth of the Swedish nation to Magog, who would have disembarked in the Stockholm archipelago eighty-eight years after the Flood. flourished into a magnificent civilization, unparalleled in the history of mankind, until 836 years after the Flood, when King Magog’s descendants set out on mission of conquest, capturing large parts of Europe and spreading the virtues of Gothic high culture.[36]

Bureus drew extensively from the Flemish alchemist Gerhard Dorn (ca. 1530 – 1 584), one of the foremost popularizers of Paracelsus’ works. Dorn presented an account of how Adam’s sons, to preserve his divine wisdom for future generations, engraved two tablets of stone describing “all natural arts in hieroglyphical characters.” After the Flood, one of these tablets was found on Mount Ararat by Noah, who passed on the knowledge on to his descendants. From them it later spread to Chaldea, Persia and Egypt, where it was advanced by Hermes Trismegistus.[37] For Bureus, Dorn’s account was significant as Noah’s grandson Magog, ancestor of the Goths, would have brought the wisdom of Adam to Sweden.[38]

Influenced by the Renaissance notion of a prisca theologia, Bureus also claimed that all ancient knowledge originally stemmed from the Goths, who had taught the Greeks and the Romans. This idea was intimately tied to Bureus’ theory that the old Scandinavian alphabet, the runes, which constituted a “Gothic Cabala.”[39] These characters he called “adelrunor” or “noble runes,” from the Swedish words adel, meaning noble, and runa, which he believed to stem from the Swedish word röna, meaning to receive or experience something.[40] Quoting from Johannes Reuchlin’s De arte cabalistica (1517) verbatim, Bureus described this “Cabala Gothorum” as a “symbolic theology,” in which the runic letters were signs of divine secrets, leading the one who could fathom their full meaning to a union with the ultimate godhead, the principium absolutis entis.[41]

Bureus also added to Dorn’s claims with Pico della Mirandola’s similar account of the prisca theologia in his Oratio, where he singled out “Xalmosis, whom Abaris the Hyperborean imitated,” as one of the first practitioners of natural magic.[42] Zalmoxis was described by Herodotus and Plato as a pupil of Pythagoras, and teacher of the Druids.[43] Zalmoxis later became demigod of the ancient Goths whose deeds were described in the well-known sixth-century Getica of Jordanes. The Getica inspired Bureus to identify the legendary Hyperboreans, the mythic lands in the far north, with the Scandinavian peninsula, prompting him to identify Zamolxis and his disciple “Abaris the Hyperborean” as the two foremost of the ancient Gothic sages.[44] However, according to Bureus it had been the Swede Abaris who had taught Pythagoras all the secrets of philosophy, thereby passing the wisdom of the Scandinavians on to the Greeks. Bureus described Zamolxis as the keeper of the secrets of the “adelrunas.”[45]

From 1616 to 1618, Bureus produced no less than three Rosicrucian pamphlets building up to his claim about the secret of the Runes and their Gothic past. In his Rosicrucian writings, Bereus advanced the idea of the ancient Goths as the original rulers of Europe—from Italy and Spain in the south to England in the north—which provided justification to Sweden’s political ambitions, a theory which was to remain the officially endorsed version of Sweden’s history until well into the eighteenth century.[46] When Bureus had read the Fama, he published his FaMa e sCanzIa reDUX (1616), which in seven sections presents biblical verses pointing to the dawning of the new age. Bureus draws special attention to Balaam’s passage in Numbers 24:17 on the coming of “a star out of Jacob and a sceptre [that] shall rise out of Israel.” To Bureus, the text was an allusion to the significance of the new star in the Swan in 1602, also called the Northern Cross, and the second new star in Serpentario in 1604, both spoken of in the Fama as presaging the new era of illuminating grace.[47]

Bureus collaborated in his promotion of the Lion of the North mythology with Joachim Morsius, a close friend of Balthazar Walther, and one of the most knowledgeable of Rosicrucians outside of Tübingen.[48] In 1623, the expected great conjunction appeared, and activities on all fronts were set in motion to form a new Protestant alliance. On the advice of Prince August of Anhalt-Plötzkau, Morsius repeated the Lion prophecy.[49] In November 1623, the ex-Palatine administrator Ludwig Camerarius set out on a “secret” mission to Stockholm to find out whether Sweden would support the Palatinists by making peace with the Danes. England followed up on the Palatinist diplomacy by sending Robert Anstruther to Denmark. More secretly in 1624, the Prince of Wales and Fredrick V sent James Spens to Stockholm with assurance of subsidies from England if Sweden took command of the evangelical forces, specified as 36 legions and 8,000 equestrian troops.[50] In 1627, Spens was dispatched to invest Gustavus with the Order of the Garter.[51] Spens then moved on to Elbing, where he recruited John Dury as his secretary.[52]

In 1625, Bureus received a letter from Duke August of Anhalt-Plötzkau with a letter from Morsius and two texts including material from the edition of the lion prophecy. Paracelsus’ was reedited and printed in 1619 as De Tinctura Physicorum, which now added the coming of der Löwe aus Mitternacht (“The Lion of Midnight”). Morsius refers to Bureus and to his Rosicrucian text, FaMa e sCanzJa reDVX (1616). Echoing the well-known prophecy of the Polish alchemist Michael Sendivogius (1566 – 1636) on Elias Artista, he adds that the art of theosophists, Kabbalists, and alchemists will now certainly ensure the rise of a metallic kingdom in the far north.[53]

For his diary, Bureus used the yearly almanacs of Finnish astronomer Sigfrid Aronius Forsius, who wrote that an age of great reform was soon to commence. Forsius appealed to the tradition of Arabic astrology, to the medieval authors Abu Ma’shar, Abraham the Jew, and John of Seville.[54] In June 1619, the ecclesiastical council in Uppsala seized Forsius’ controversial tract, which referred to the comet in the Swan of 1602, and a great conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn appeared in Serpentario in 1603/04. Forsius explained that these signs reproduced the saying made popular during the radical reformation, “after the burning of the Goose there will follow a Swan,” a saying fulfilled by the burning of the founder of the Moravian Brethren, Johan Hus (meaning goose) in 1417 and by Luther a hundred years later. While Hus, the founder of the Hussites who were to become the Moravian Brethren, was the second Noah, Luther was the third Elijah.[55]

Queen Christina

Dispute of Queen Cristina Vasa and René Descartes.

Christina, Queen of Sweden (1626–1689).

Bureus’ manuscript Adulruna Rediviva, a first version of which was given to Gustav Adolf on his assumption to the Swedish throne in 1611, was given as a gift to Christina in 1643. Christina became queen-elect before the age of six after her father died in the Battle of Lützen in 1932. Her father had also arranged for her to receive an education of the type normally only afforded to boys. In all her biographies, her gender and cultural figure prominently. It was said that Christina “walked like a man, sat and rode like a man, and could eat and swear like the roughest soldiers.”[56] According to Veronica Buckley, Christina was a “dabbler” who was “…painted a lesbian, a prostitute, a hermaphrodite, and an atheist.” [57]

Christina was not only read on the subject of alchemy, but was also a practitioner in the laboratory. Christina had been approached by the alchemist Johannes Franck (1590 – 1661), a professor of pharmacology at Uppsala University, where he was part of the introduction of “the doctrines of Theophrastus and Trismegistos.” The Polish adept Michael Sendivogius, explained Åkerman, had a definite Influence in Christina’s Sweden through Franck’s alchemical allegory Colloquium with Mountain Gods (1651). It describes the genealogy of a royal family that finally bring forth the daughter Aurelia áurea, the perfect gold. Sendivogius’ work with boiling “heavenly dew” is implied and described as working “de rore coell.” Franck saw Christina’s reign the fulfillment the Polish adept Michael Sendivogius’ prophecy of a new alchemical monarchy in the North, and Paracelsus’ prophecy concerning the alchemical adept Elias Artista.[58] Franck expressed his ideas in an alchemical allegory he dedicated to her: Colloquium philosophicum cum diis montanis (Philosophical Conversation with Mountain Gods, 1651). Franck’s story described Zalmoxis being led by a dwarf to meet with the queen of the mountain, Aurelia áurea, the perfect gold. As Ákerman summarized:

We cannot directly confirm that Christina read or heard about these grand expectations. But there is a possibility that already early on she understood her prophetic role, even if she was to fulfil it first through the Peace of Westpbalia in 1648, and then through her conversion to Catholicism. Thereafter she gained a renewed possibility to influence European politics: she attempted to become vice-regent of Naples in 1657, and was admitted to negotiations between France and Spain—the universal peace was in sight.[59]

Sendivogius demonstrating an alchemical transmutation to Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund III.

As detailed by Susanna Åkerman, Christina’s library contained approximately 4500 printed books and 2200 manuscripts on the subjects of Hermeticism, Neoplatonism, alchemy, Kabbalah and prophetic works. A central manuscript in Christina’s collection is the ancient Hermetic dialogue Asclepius. She owned copies of the Orphic Hymns and is described as “trembling with joy” when she received a copy of Iamblichus’ De Mysteriis aegyptiorum, chaldeorum et assyriorum describing methods and practices of theurgy and divination, the ascent of the soul and how to come into contact with gods and demons.[60] Christina persuaded the specialist in Greek, Johannes Schefferus, to write a history of the Pythagoreans, the first modern history of its kind.[61]

Christina was led to Platonism early through readings of the Pico della Mirandola. She owned a Ficino’s commentary on Plato’s Parmenides. In her collection was Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia and controversial description of constructing magical seals and of summoning hidden spirits living in the dark; a volume of Giordano Bruno’s De triplico minimo et mensur condemned by the Church; Trithemius’ Steganographia; John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica; and the collected works of Paracelsus. Furthermore, there were exclusive works by astronomers and astrologers such as Ptolemy, the Picatrix, several copies of The Emerald Tablet of Hermes, al Kindi, Albohaly, Abu Ma’shar, Alfraganus, Albohazen, Mesahala, Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Kepler, Christoph Scheiner, Johannes Regiomontanus, and Gallileo, and Robert Fludd

Christina’s section of Hebraica included more than a hundred titles, of which no less than 38 were commentaries on Jewish mysticism and just the Christian kabbalah, but the original Jewish. The Sefer Yezirah and parts of the Zohar are accompanied by Messianic writers such as Rabbi Aquiva and Isaac Abarbanel, and followed by commentaries of the Messianic Kabbalists active in Italy, such Moses Almonsini, Menahem Recanati, and Salomon Molkho.[62]

Christina’s practise in alchemy preoccupied her for most of her adult life, and she maintained numerous connections to Rosicrucians. Christina’s tutor, Johannes Matthiae, influenced by John Dury and Comenius. In 1642, Comenius was in Sweden to work with Queen Christina and the Lord High Chancellor of Sweden, Axel Oxenstierna, on reorganizing the educational system in Swedish. In 1649, Christina invited Descartes— who by then had become famous throughout Europe for being one of the continent’s greatest philosophers and scientists—to Stockholm to start an academy. According to his biographer Baillet, one of Descartes’ reasons for accepting the invitation was to plead on behalf of the Princess Elizabeth and the Palatinate at the Swedish court. The plan failed however, because Descartes and Queen Christina turned out to ultimately dislike one another. Finally, because the cold climate led Descartes caught a chill that turned into pneumonia and killed him.[63]

Christina’s scholarly gatherings in Stockholm were originally arranged in 1649 by the Dutch Greek scholar Isaac Vossius (1618 – 1689), who brought in colleagues such as the classical humanists Nicholas Heinsius and Johann Freinshemsius. The French humanists Claude Saumaise, Samuel Bochart, Gabriel Naudé and Pierre Daniel Huet also soon appeared at the Swedish court. One of the themes discussed was Bochart’s thesis on the northern cruises of the ancient Phoenicians. He presented evidence from antiquity that Phoenician sailing ships certainly reached the British Isles and perhaps even farther north.[64]

Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (1602 – 1680)

Abraham van Franckenberg (1593 – 1652)

Christina caused a scandal when she decided not to marry and in 1654 when she abdicated her throne and converted to Roman Catholicism. It is well known that her abdication and conversion to Catholicism was preceded by secret talks with Jesuits.[65] According to Frances Yates, “of all the branches of the Roman Catholic Church it was the Jesuits who were most like the Rosicrucians.”[66] In 1646, von Franckenberg had also sent a copy of Bureus’ FaMa e sCanzIa reDUX to Kircher.[67] Before the arrival of the Jesuits, whom she had specifically asked to be skilled in mathematics, Christina was in secret contact with the Roman Jesuit and polymath Athanasius Kircher (1602 – 1680). He was taught Hebrew by a rabbi in addition to his studies at school.[68] He became a professor of ethics and mathematics and also taught Hebrew and Syriac. Beginning in 1628, he also began to show an interest in Egyptian hieroglyphs. Kircher claimed to have deciphered the hieroglyphic writing of the ancient Egyptian language, but most of his assumptions and translations in this field were later found to be incorrect.

Ignoring the Casaubon’s critique of the Corpus Hermeticum, Kircher interpreted all Egyptian monuments as having written on them in the hieroglyphs the truths of Hermes Trismegistus. In Oedipus Aegyptiacus, Kircher wrote:

Hermes Trismegistus, the Egyptian, who first instituted the hieroglyphs, thus becoming the prince and parent of all Egyptian theology and philosophy, was the first and most ancient among the Egyptians and first rightly thought of divine things; and engraved his opinion for all eternity on lasting stones and huge rocks. Thence Orpheus, Musaeus, Linus, Pythagoras, Plato, Eudoxus, Parmenides, Melissus, Homerus, Euripides, and others learned rightly of God and of divine things… And this Trismegistus was the first who in his Pimander and Asclepius asserted that God is One and Good, whom the rest of the philosophers followed.[69]

The abduction of Persephone and other ancient myths interpreted as symbols of esoteric wisdom, from Kircher’s Pamphilian Obelisk (1650)

Kircher cited as his sources Chaldean astrology, Hebrew Kabbalah, Greek myth, Pythagorean mathematics, Arabian alchemy and Latin philology. Kircher claimed to have deciphered the hieroglyphic writing of the ancient Egyptian language, but most of his assumptions and translations in this field were later found to be incorrect. In Oedipus Aegyptiacus, he argued Hieroglyphica was the language spoken by Adam and Eve, that Hermes Trismegistus was Moses, and that hieroglyphs were occult symbols which “cannot be translated by words, but expressed only by marks, characters and figures.” Kircher’s work, according to Yates, was much used in missionary efforts, as he tried to make use of the Dee tradition, by illustrating an “Egyptian” version of the Monas symbol in one of his volumes.[70]

Kircher was a protégée of Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597 – 1 679), the nephew of Urban VIII, born Maffeo Barberini, who was educated by the Jesuits, and later issued the papal bulls of canonization for Ignatius of Loyola. Urban VIII practiced nepotism on a grand scale, leading various members of his family to become enormously rich through him, so that it appeared to contemporaries as if were establishing a Barberini dynasty.[71] He elevated his brother Antonio Marcello Barberini and then his nephews Francesco and Antonio Barberini to Cardinal. As the Grand Inquisitor of the Roman Inquisition, a post he held from 1633 until his death, Cardinal Barberini was part of the Inquisition tribunal investigating Galileo, he was one of three members of the tribunal who refused to condemn Galileo.

Hugo Grotius (1583 – 1645)

In addition to Kircher, Cardinal Barberini supported numerous European intellectuals, scholars, scientists and artists, including Kircher, Jean Morin, Gabriel Naudé, Gerhard Johann Vossius, Heinsius and John Milton.[72] Gerardus Vossius (1577 – 1649) was the son of Johannes (Jan) Vos, a Protestant from the Netherlands, who fled from persecution into the Electorate of the Palatinate. Vossius became the lifelong friend of Hugo Grotius (1583 – 1645), who helped lay the foundations for international law, based on natural law. Grotius studied with some of the most acclaimed intellectuals in northern Europe, including Joseph Justus Scaliger.[73]

Gerardus Vossius (1577 – 1649)

Milton was introduced to Barberini, who invited him to an opera hosted by the cardinal.[74] Cardinal Mazarin had also given protection for a time to kliu\Barberini, whom Naudé served as a librarian. Nicolaas Heinsius the Elder (1620 – 1681) was a Dutch classical scholar and poet. Heinsius called to Stockholm by Queen Christina, at whose court he waged war with Claudius Salmasius, an intimate with Isaac Casaubon, and an ally of Vossius. Salmasius accused Heinsius of having supplied Milton with facts from the life to write Defensio pro Populo Anglicano.[75] This work was a piece of propaganda commissioned by Parliament during Cromwell’s protectorship as a response to a work by Salmasius entitled Defensio Regia pro Carolo I (“Royal Defence on behalf of Charles I”). Salmasius argued that the rebels led by Cromwell were guilty of regicide for executing King Charles, while Milton responded with a detailed justification of the parliamentary party.

Claudius Salmasius (1588 – 1653)

Cardinal Barberini appointed Kircher as tutor and confessor to Prince Friedrich von Hesse-Darmstadt. The Prince converted in 1637, and was accompanied by Kircher to Malta, where he was soon admitted into the Knights of Malta.[76] The Jesuits attained a certain influence on the organizational structures of the Order, particularly during the opening years of the reign of the French Grand Master Jean Paul de Lascaris Castellar (1560 – 1657), whose confessor was the Maltese Jesuit Father Giacomo Cassia.[77] By sending Kircher to Malta, Barberini fulfilled Lascaris’ long-term wish for a mathematician for the Collegium Melitense to instruct the novices of the Order.[78] Kircher who was on the island of Malta early 1638. During his stay, he is reputed to have built machine called the Specula Melitensis Encyclica, or “the Maltese Observatory,” because Kircher dedicated it to the Knights of Malta. The machine, which he supposedly build on the island, was intended to function as a “new physics mathematical machine.”[79] Kircher claimed his observatory could chart the movements of the planets, predict storms and winds, as well as establish the times and locations of future eclipses, and “discovering medical agents with occult powers.”[80]

Lascaris wrote to Cardinal Barberini, expressing his concern over a recent incident, in which the Maltese locals rose up in protest against the Jesuits’ condemnation of certain observances of Carnival in 1639. As related by Buttigieg, as was the case elsewhere, the Jesuits sought to rein in Carnival which was generally associated with sinful revelry, but which in Malta was highly regarded by Hospitallers, many of whom, in particular the knights, came from Europe’s leading noble families.[81] Following public protest, the Jesuits were formally, though temporarily, expelled from Malta.

In 1652, Prince Friedrich was elevated to cardinal by Pope Innocent and participated in the Papal conclave of 1655. He was appointed papal legate to Queen Christina of Sweden. When Pope Innocent X died in 1655, his successor was a friend of Kircher and Cardinal Barberini, Fabio Chigi (1599 –1667), who took the title of Alexander VII. Chigi had been in correspondence with Gustavus Adolphus II, and had heard of Christina’s interest in the Catholic Church.[82] Christina had caused a scandal when she decided not to marry and in 1654 when she abdicated her throne and converted to Roman Catholicism. It is well known that her abdication and conversion to Catholicism was preceded by secret talks with Jesuits.[83]

In 1651, Kircher sent Christina his Musurgia Universalis sive ars magna consoni et dissoni, an encyclopedia of music, with comments on acoustics, musical harmonies and the scale of tones forming the Soul of the World. In a letter, Kircher also spoke briefly of his work Oedipus Aegyptiacus and also presented ancient Egyptian revelations, Jewish mysticism in the form of Kabbalah and oriental magic. Kircher even addressed Christina in November 1651 as Regina serenissima, potentissima, sapientissima, vere trismegisti (“A Queen most exalted, most powerful, and most wise, truly belonging to the three times great”), referring to Hermes Trismegistus.[84]

Christina mentioned in her answer to Kircher that her letter was carried by Francisco Macedo, a Portuguese Franciscan theologian and Jesuit who was the first to respond to Christina’s wish to discuss Catholicism. Macedo had arrived in disguise in Stockholm in 1650, as part of the entourage of the Portuguese Ambassador. In September 1651, he reported to the Jesuit General Goswin Nickel that Christina wanted to have secret discussions on Catholicism. Paolo Casati, a mathematician and colleague of Kircher at the Collegio Romano, and Francesco Malines were chosen to travel to Sweden incognito to meet with her. Casati was the author of the astronomical work Terra machinis mota (1658), which imagines a dialogue between Galileo, Paul Guldin, and Marin Mersenne on various intellectual problems of cosmology, geography, astronomy and geodesy. The work is remarkable in that it represents Galileo in a positive light, in a Jesuit work, only 25 years after his condemnation by the Church. The crater Casatus on the Moon is named after him. On her arrival in Rome on Christmas day 1655, Kircher dedicated to Christina his book Itinerarium exstaticum coeleste, the ecstatic journey through the heavens, a dialogue between the angel Cosmiel and the pupil Theodidactus on a fictional journey through the Solar system as presented by Tycho Brahe in a compromise version.[85]

In December 1655, Pope Alexander VII received Christina in splendor at Rome, where she was a sensation. Missing the activity of ruling, she entered into negotiations with the French chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, and with Francesco I d’Este, Duke of Modena (1610 – 1658), also a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, to become queen of Naples—then under the Spanish crown—and to leave the throne to a French prince at her death. This scheme collapsed in 1657, during a visit by Christina to France. The Pope described her as “a queen without a realm, a Christian without faith, and a woman without shame.”[86] In spite of this scandal, Christina lived to become one of the most influential figures of her time, the friend of four popes, and a munificent patroness of the arts. She was renowned, too, for her militant protection of personal freedoms, for her charities, and as protectress of the Jews in Rome. In Rome, she made Pope Clement X prohibit the custom of chasing Jews through the streets during the carnival. In 1686, she issued a declaration that Roman Jews were under her protection.[87]

After the death of Gustavus Adolphus at Lützen in 1632, a curved magical sword that had been found on his blood-stained body was presented to the royal astrologer Jean-Baptiste Morin in Paris. When Christina passed through Paris in 1656, and was shown the sword, Morin told her that Kircher had deciphered its astrological signs as invocations to the angels Seraphiel, Harbiel, Maladriel, Kiriel, and Uziel—the Kabbalistic angels of protection, of flames, of resolve, of diversion, and of force.[88]

[1] Daniel Riches. “Gustavus Adolphus.” Dictionary of Luther and the Lutheran Traditions (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Publishing Group, 2017).

[2] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 125.

[3] Ibid., p. 112.

[4] Cited in Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 317.

[5] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 221.

[6] H. R. Trevor-Roper. Religion, the Reformation, and Social Change (London, 1967), p. 256; as cited in Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 226.

[7] Lisa Shapiro. “Elisabeth, Princess of Bohemia.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/elisabeth-bohemia

[8] Lloyd Strickland (ed. and transl.). Leibniz and the Two Sophies: The Philosophical Correspondence, (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2011).

[9] Frances Yates. “Science, Salvation, and the Cabala” New York Review of Books (May 27, 1976 issue); Hugh Trevor-Roper. The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1967).

[10] Ibid., p. 232.

[11] Ibid., p. 233.

[12] Ibid., p. 249.

[13] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 193.

[14] Yates. The Occult Philosophy of the Elizabethan Age, p. 208.

[15] Chris Mathews. Modern Satanism: Anatomy of a Radical Subculture (Wesport: Praeger, 2009) p. 54.

[16] Denis Saurat. Milton: Man and Thinker (London, 1944); cited in Frances Yates. The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age (New York & London: Routledge, 1979). p. 208.

[17] R.J. Zwi Werblowsky, “Milton and the Conjectura Cabbalistica,” Journal of the Warburg Courtauld Institutes, XVIII (1955), p. 110. etc.; cited in Frances Yates. The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age (New York & London: Routledge, 1979). p. 208.

[18] Trevor-Roper. The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century, p. 233.

[19] Ibid., p. 234.

[20] Allison Coudert. The Impact of the Kabbalah in the Seventeenth Century: The Life and Thought of Francis Mercury Van Helmont (1614-1698) (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1999), p. 28.

[21] Trevor-Roper. The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century, p. 234.

[22] Gary Lachman. The Secret Teachers of the Western World (Penguin, 2015), p. 299.

[23] Trevor-Roper. The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century, p. 235.

[24] Hugh Chisholm, ed. “Sigismund.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911).

[25] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 203.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Clare Goodrick-Clarke, “The Rosicrucian Afterglow.” The Rosicrucian Enlightenment Revisited, (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1999) p. 209.

[28] Trevor-Roper. The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century, p. 235.

[29] Paul Heidebrecht and The Editors. “Meeting of the Minds.” Christian History. Retrieved from https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-13/meeting-of-minds.html

[30] Ruth Stephan. “Christina, Queen of Sweden.” Encyclopedia Britannica.

[31] Håkan Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths: Johannes Bureus’ Search for the Lost Wisdom of Scandinavia.” Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012), p. 500.

[32] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 48.

[33] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 203.

[34] Bureus’ MS. F.a.3. f. 156v, 145, 41, Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm; as cited in Susana Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 30.

[35] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 44; N24, 47r–48r, quoting and glossing Reuchlin, De arte cabalistica (Hagenau, 1517), 52r, 21v; cited in Håkan Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths: Johannes Bureus’ Search for the Lost Wisdom of Scandinavia.” Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012), p. 506.

[36] Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths,” p. 502.

[37] Congeries Dorn, pp. 154-155, as cited in Håkan Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths: Johannes Bureus’ Search for the Lost Wisdom of Scandinavia.” Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012), p. 508.

[38] Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths,” p. 509.

[39] Ibid., p. 505.

[40] Ibid., p. 507.

[41] N24, 47r–48r, quoting and glossing Reuchlin, De arte cabalistica (Hagenau, 1517), 52r, 21v; cited in Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths,” p. 506.

[42] Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths,” p. 510.

[43] Refutation of All Heresies, Book I, chap. XXII.

[44] N24, 99v–100r , 138r, 185r; as cited in Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths,” p. 511.

[45] N24, 71r, 101r, 132r–v, 159v; as cited in Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths,” p. 511.

[46] Håkan Håkansson. “Alchemy of the Ancient Goths: Johannes Bureus’ Search for the Lost Wisdom of Scandinavia.” Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012), p. 502.

[47] Åkerman. “Three phases of inventing Rosicrucian tradition in the seventeenth century,” p. 167.

[48] See Penman, “A Second Christian Rosencreuz?” p. 163.

[49] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 159.

[50] Ibid. p. 28.

[51] Edward Irving Carlyle (1898), “Spens, James,” in Lee, Sidney, Dictionary of National Biography, 53, (London: Smith, Elder & Co), p. 392.

[52] Ibid., p. 391.

[53] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 139-140.

[54] Ibid., p. 127.

[55] Ibid., p. 126-127.

[56] Veronica Buckley. Christina, Queen of Sweden: The Restless Life of a European Eccentric (HarperCollins, 2004).

[57] Ibid.

[58] Susanna Ákerman. “Sendivogius in Sweden: Elias Artista and the Fratres roris cocti.” Aries - Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism, 14 (2014), p. 62.

[59] Ibid., p. 71.

[60] Åkerman. “Hermeticism in Sweden,” in Western Esotericism in Scandinavia (BRILL, Mar. 31, 2016).

[61] Tore Ahlbäck & Björn Dahla. Western Esotericism: Based on Papers Read at the Symposium on Western Esotericism, Held at Åbo, Finland on 15-17 August 2007 (Donner Institute, 2008), p. 21.

[62] Susanna Åkerman. “Queen Christina’s Esoteric Interests as a Background to Her Platonic Academies.” Western Esotericism. Vol 20 (2008).

[63] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 155.

[64] Åkerman. “Queen Christina’s Esoteric Interests as a Background to Her Platonic Academies.”

[65] Ibid., p. 22.

[66] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 289.

[67] Susanna Åkerman. “Queen Christina’s Esoteric Interests as a Background to Her Platonic Academies.” Western Esotericism. Vol 20 (2008), p. 22.

[68] John Edward Fletcher. A Study of the Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher, ‘Germanus Incredibilis’: With a Selection of His Unpublished Correspondence and an Annotated Translation of His Autobiography (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

[69] op. cit., I l l , p. 568; cited in Yates. Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, p. 418.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Leopold von Ranke. History of the popes; their church and state (Volume III) (The Colonial Press, 1901).

[72] Torgil Magnuson. Rome in the Age of Bernini, volume 1, (Stockholm, 1982), p. 239.

[73] Hamilton Vreeland. Hugo Grotius: The Father of the Modern Science of International Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 1917), Chapter 1.

[74] John Milton & Henry John Todd. The Poetical Works of John Milton: With Notes of Various Authors; and with Some Account of the Life and Writings of Milton, Derived Principally from Original Documents in Her Majesty's State-paper Office, Volume 4 (Rivingtons, Longman and Company, 1852), p. 420.

[75] Charles Symmons. The Life of John Milton (London: G. and W. B. Whittaker, 1822), p. 292.

[76] Emanuel Buttigieg. “Knights, Jesuits, Carnival and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century Malta.” The Historial Journal, 55(3), September 2012, p. 580.

[77] Ibid., p. 573.

[78] Ibid., p. 580.

[79] Dr. Mark A Waddell. Jesuit Science and the End of Nature’s Secrets (Surrey: Ashgate, 2015), p. 183.

[80] Ibid..

[81] Buttigieg. “Knights, Jesuits, Carnival and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century Malta,” p. 573.

[82] John Edward Fletcher. A Study of the Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher, ‘Germanus Incredibilis’: With a Selection of his Unpublished Correspondence and an Annotated Translation of his Autobiography (Leiden: Brill, 2011), p. 46.

[83] Susanna Åkerman. “Queen Christina’s Esoteric Interests as a Background to Her Platonic Academies.” Western Esotericism. Vol 20 (2008), p. 22.

[84] Ibid., p. 22.

[85] Ibid., p. 23.

[86] Ivan Lindsay. The History of Loot and Stolen Art: from Antiquity until the Present Day (Andrews UK Limited, 2014).

[87] “Wasa, Kristina - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.” www.iep.utm.edu. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

[88] Åkerman. “Queen Christina’s Esoteric Interests as a Background to Her Platonic Academies.” p. 166.

Volume Two

The Elizabethan Age

The Great Conjunction

The Alchemical Wedding

The Rosicrucian Furore

The Invisible College

1666

The Royal Society

America

Redemption Through Sin

Oriental Kabbalah

The Grand Lodge

The Illuminati

The Asiatic Brethren

The American Revolution

Haskalah

The Aryan Myth

The Carbonari

The American Civil War

God is Dead

Theosophy

Shambhala